The Catholic Revival in English Literature by Ian Ker is not, as its title suggests, the study of a literary movement. It is instead a collection of six free-standing essays about six very different writers: John Henry Newman, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Hilaire Belloc, G. K. Chesterton, Graham Greene, and Evelyn Waugh.

Some of these men were friends; some were influences on one another; but as a group they had surprisingly little in common apart from their faith. Belloc, who knew Cardinal Newman as a student at his Oratory school in Birmingham, always preferred Newman’s great rival, Cardinal Manning. Evelyn Waugh admired Chesterton the thinker but considered him a careless writer. (Waugh even toyed with the idea of rewriting The Everlasting Man to rescue it from its Fleet Street barbarism.) In verse, Hopkins was a modernist before his time, Belloc a Victorian behind his. Greene and Waugh were contemporaries at Oxford and knew each other well. But while they were respectful of each other’s work, they had radically different temperaments and wrote radically different novels. Think of The End of the Affair and A Handful of Dust : both stories about adultery, and both Catholic stories about adultery. Aside from that, they could hardly be more different. In A Handful of Dust , Waugh treats adultery as something ugly and frivolous”more an expression of anomie than of lust. If it weren’t such an efficient engine of destruction, the act itself would be hardly worth our notice. In Greene’s novel, by contrast, adultery is anything but frivolous: it may be either the occasion of despair or the beginning of conversion, but whatever else it is, it is always a subject of fascination. Here Greene and Waugh were working two sides of the same street, but that is as close as they would ever get. By the end of their careers, they were living and writing in different worlds.

So, then, why these six writers? In his preface, Ker suggests two principles of selection. The first has to do with the connection between what these men wrote and what they believed. Joseph Conrad, Edith Sitwell, and Siegfried Sassoon were all baptized Catholics. But in Ker’s view, they cannot fairly be counted as Catholic writers, since Conrad had stopped practicing his faith before he began to write and Sitwell and Sassoon had stopped writing before they became Catholics. Such disqualifications seem fair enough, but Ker is just as fussy about those who were already, or still, Catholic when they were writing. In the work of a novelist such as Ford Madox Ford (described by Ker as a “very intermittent Catholic”), religion plays too small a role. Ford’s novels often address the incidental attributes of English Catholicism, especially its connection with what Ker calls “feudal Toryism,” but the essential drama of faith remains out of view. Among those who were truly Catholic writers according to Ker’s rigorous definition”including Robert Hughe Benson and Maurice Baring”Ker’s six stand out because they are still widely read and studied by Catholics and non-Catholics alike.

But even when one knows why Ker chose not to include, say, Francis Thompson or David Jones, one is still left wondering why he decided to write about his finalists in a single book. Yes, both Hopkins and Greene were great writers, and surely both wrote as Catholics, but there the resemblance appears to end. For all the reasons mentioned above, as well as many others, most readers will have trouble thinking of these men as belonging to any kind of group.

To his credit, Ker makes no effort to conceal the striking differences among his subjects. He allows the writers to speak for themselves, quoting generously”sometimes excessively”from their best work. He doesn’t say much about Belloc’s deep strain of melancholy, but we find it anyway, in Belloc’s own words. In a passage cited by Ker, Belloc wrote that it was only the faith that protected him from “the extreme of harm, final harm, despair.” As a young man at art school, Chesterton had his own demons to contend with, but by the time he emerged as a critic and journalist, his most striking quality was an almost Dickensian cheerfulness. Of all the writers covered in this book, Chesterton and Belloc were the closest in sympathy and conviction; nevertheless, George Bernard Shaw’s “Chesterbelloc” would have been a creature with a violent mood disorder.

Allowing for the remarkable contrasts, Ker believes he can still trace at least one theme through the work of all six of his subjects, a theme that has little to do with the obvious “motifs” of English Catholicism such as “aestheticism, a love of ritual, ceremony, tradition, the appeal of authority, a romantic triumphalism, the lure of the exotic and foreign, a preoccupation with sin and guilt.” What Ker discovers instead is a common concern for the “sheer ordinariness” of Catholic Christianity, the everyday “matter-of-factness” of its sacraments and sacramentals. Whereas Protestantism was for these writers a religion of words and inchoate dispositions, the Catholic “Thing” was a religion of hard facts and regular practices, a religion that offered definition in place of Protestant sentiment.

Ker is best known as a Newman scholar, and so it is not surprising that he sees this theme most clearly through the prism of Newman’s genius. It was history and theology that had first drawn Newman to the Catholic Church. Even as an Anglo-Catholic, he knew little about Roman Catholic practices and made a point of avoiding Catholics themselves. As Ker writes, “In Newman’s case . . . the discovery of Catholicism was a consequence rather than a cause of conversion.” What Newman discovered in his new Church was a religion that was never off-duty and never afraid of vulgar piety. In the Catholic cultures Newman saw after he was received into the Church, religion was not merely part of one’s daily routine; it was the ground of that routine, something confidently, unpretentiously taken for granted. In Difficulties of Anglicans , a set of lectures written just after his conversion and addressed to the Anglo-Catholic community he had left behind, Newman describes the scene outside a Catholic church during a fiesta:

The chef d’oeuvre of the exhibition is the display of fireworks to be let off as the finale . “How unutterably profane!” again you cry. Yes, profane to you . . . profane to a population which only half believes; not profane to those who, however coarse-minded, however sinful, believe wholly . . . . They gaze, and, in drinking in the exhibition with their eyes, they are making one continuous and intense act of faith.

This was to be contrasted with the delicacy of Anglican ritual, in which doctrinal insecurities were disguised with elevated language and self-conscious displays of solemnity:

Since, too, they have no certainty of the doctrines they profess, they do but feel they ought to believe them, and they try to believe them, and they nurse the offspring of their reason, as a sickly child, bringing it out of doors only on fine days . . . . So they keep the exhibition of their faith for high days and great occasions, when it comes forth with sufficient pomp and gravity of language, and ceremonial of manner. Truths slowly totter out with Scripture texts at their elbow, as unable to walk alone. Moreover, Protestants know, if such and such things be true, what ought to be the voice, the tone, the gesture, and the carriage attendant upon them . . . . They condemn Catholics, because, however religious they may be, they are natural, unaffected, easy, and cheerful in their mention of sacred things; and they think themselves never so real as when they are especially solemn.

Here is a side of Newman that rarely gets much attention. The great defender of traditional liturgy could also be its critic when he thought the fog of incense was merely hiding a vacancy at the altar. And the most elegant prose stylist of the Victorian era had no time for lofty language if it was used as a brake on popular devotion.

Ker argues that it was the language of Catholic popular devotion”in particular the language of litanies”that helped Hopkins bring English verse back into contact with everyday speech. Similarly, it was the common duties of the Catholic priesthood that inspired so much of his religious imagination. For Hopkins, the priest was above all a kind of craftsman. Unlike “the amateur, educated, gentlemanly Anglican clergyman” (Ker’s phrase), the Catholic priest was a classless professional with a job to do, a job that involved his hands as much as his voice. In “Felix Randal,” the sacraments of penance and last rites are as physical as the farrier’s old labor and the illness that ends it.

This notion of Catholicism as a solid, objective religion”and of Protestantism as a prison of introspection”reappears somewhat more crudely in the work of both Belloc and Chesterton. Belloc believed, with Cardinal Manning, that all human conflicts were ultimately theological, and that the conflict between Protestantism and Catholicism in particular was a disagreement about the importance of definition. According to Belloc, Protestants disliked the idea of definition in religion because it reminded them of limitation and constraint. But as Chesterton would argue, limitation was a necessary condition of all beauty. “Art is limitation; the essence of every picture is the frame . . . . The artist loves his limitations: they constitute the thing he is doing.”

Again, in Greene’s “Catholic” novels, it is always a theological definition that generates the most painful dilemmas. Scobie, the protagonist of The Heart of the Matter , can’t go to Mass with his wife because she will see that he isn’t receiving communion. He can’t receive communion because he is cheating on her and so is in a state of mortal sin. But he refuses to go to confession unless he knows he is prepared to end the affair. His mistress, who is not a Catholic, asks him why he doesn’t just “go and confess everything now? After all, it doesn’t mean you won’t do it again.”

“It’s not much good confessing if I don’t intend to try . . . .”

“Well then,” she said triumphantly, “be hung for a sheep. You are in”what do you call it?”mortal sin? now. What difference does it make?”

He thought: pious people, I suppose, would call this the devil speaking, but he knew that . . . this was innocence. He said, “There is a difference”a big difference . . . . Now I’m just putting our love above”well, my safety. But the other”the other’s really evil. It’s like the Black Mass, the man who steals the sacrament to desecrate it. It’s striking God when he’s down”in my power.”

She turned her head wearily away and said, “I don’t understand a thing you are saying. It’s all hooey to me.”

“I wish it were to me. But I be-lieve it.”

She said sharply, “I suppose you do. Or is it just a trick?”

“Striking God when he’s down”in my power”: this is powerful language but perverse theology, as Greene must have known. But he seems to have believed it was also a peculiarly Catholic kind of perversion, not because it involves an exaggerated expression of guilt”Scobie, of course, has good reason to feel guilty”but because of its obsessive concern with definition. Scobie is not satisfied with the distinction between venial and mortal sin; he needs to weigh one mortal sin against another as if to chart the available degrees of damnation.

This is one of the passages George Orwell had in mind when he wrote that “when people really believed in Hell, they were not so fond of striking graceful attitudes on its brink.” Orwell was on to something, for there does seem to be an element of fantasy in Scobie’s words, whether it’s a lunatic’s fantasy or just that of a spiritual malingerer. Ker’s book invites the reader to assume that “matter-of-factness” and a devotion to definition are always two aspects of the same quality. In fact, they often fall on opposite sides of the ledger. From the point of view of orthodox Catholic theology, as from Orwell’s very different point of view, the problem with Scobie’s speculations is that, while they are quite well defined, they are not at all matter-of-fact: his desire for definition has lurched into a kind of moral insanity. More damaging to the novel, it is not always clear to the reader why”or whether”Scobie is willing to stake his life on this fantasy. We suppose he believes what he is saying, but we can never banish the worry that he is tricking himself, as well as everyone else. In the end, he imagines he can help both his wife and his mistress by committing suicide.

The distinction between the definite and the ordinary is an important one. It was of special concern to both Newman and Chesterton, though they approached the problem from slightly different angles. Chesterton liked to talk about it as the difference between rationalism and reason, by which he meant common sense. With greater clarity and precision, Newman had described rationalism as the insubordination of reason itself. Ker is familiar with the question as it arises in Newman’s theory of knowledge, but, curiously, he never mentions it in this collection. The Catholic Revival in English Literature is a useful addition to the study of the six writers it covers. All of it is elegantly written and most of it carefully argued. Still, it would have been a better book if Ker had resolved, or at least explored, this tension in one of its unifying themes.

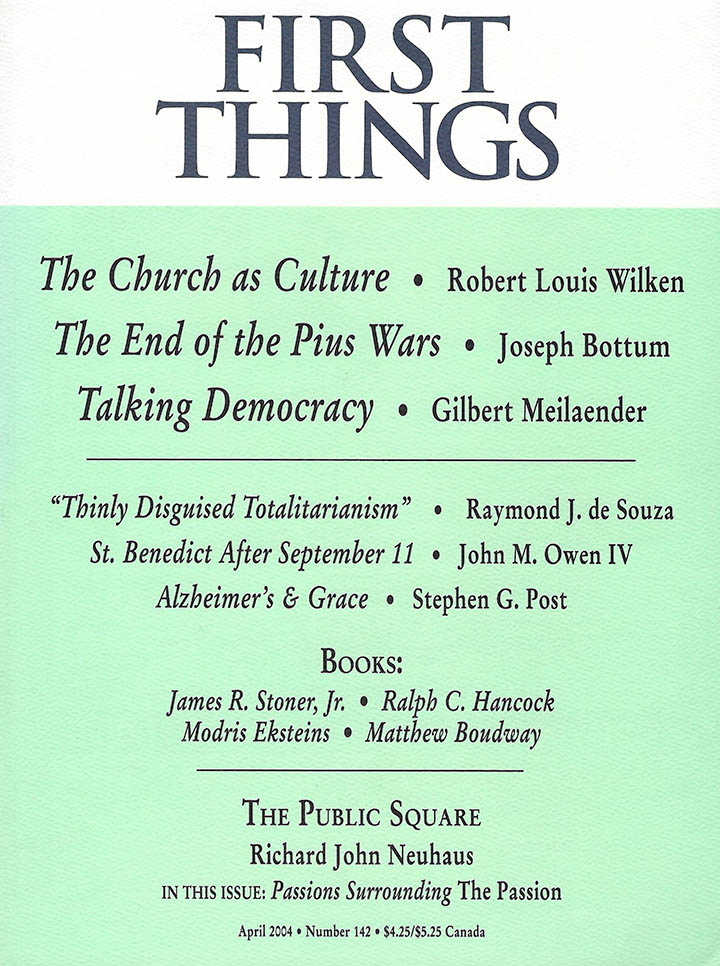

Matthew Boudway is Managing Editor of First Things.

Bladee’s Redemptive Rap

Georg Friedrich Philipp von Hardenberg, better known by his pen name Novalis, died at the age of…

Postliberalism and Theology

After my musings about postliberalism went to the press last month (“What Does “Postliberalism” Mean?”, January 2026),…

Nuns Don’t Want to Be Priests

Sixty-four percent of American Catholics say the Church should allow women to be ordained as priests, according…