Coriolanus is far from being the most popular of Shakespeare’s plays, but many of us remember the plot from high school English. Caius Martius, a great Roman warrior, conquers the Volscian city of Corioli, and for this exploit he receives the honorific title “Coriolanus.” Following his victory, Coriolanus, urged on by his ambitious mother Volumnia, stands for election as consul. To become consul, Coriolanus has to gain the support of both the patrician senate and the Roman people. Being a patrician himself, he easily secures the support of the senate, but to gain the support of the people he must don the robes of a pleb and go about the city asking, politely, for their support. This grates on the proud Coriolanus but he reluctantly follows custom and wins the post of consul. Immediately, the tribunes, who are democratic demagogues, convince the people to withdraw their support, and then provoke Coriolanus into an outburst that leads him to be charged with treason. His friends appeal to him to flatter and cajole the people to win back their support, but Coriolanus will not, and he is banished from Rome.

Coriolanus immediately goes to his old enemy, the Volscian general Aufidius, and offers to attack and conquer Rome on behalf of the Volscians. Aufidius accepts his help, and under the command of Coriolanus the Volscians win several battles and threaten Rome itself. Desperate, the Romans send Volumnia and Coriolanus’ wife, Virgilia, to convince him to withdraw. Though he steels himself to resist the pull of filial affection, Coriolanus buckles under his mother’s pleas and ends the siege. Though he knows that he has broken faith with Aufidius, he returns to the Volscians, who accuse him of treachery and kill him.

The personal drama of the story, which Shakespeare drew from Plutarch, is obvious: Volumnia must decide between loyalty to Rome and loyalty to her son; Aufidius is faced with the dilemma of accepting or rejecting his rival’s aid; Coriolanus is caught in conflicts of various sorts—between plebs and patricians, between family and civic loyalties, between the Romans and Volscians. In the end, he is torn apart.

The political drama is equally plain, and has often been exploited, though in opposite directions. A production at Drury Lane in 1789 embodied the strongly anti-Jacobin politics of its producer, John Philip Kemble, idealizing the patrician characters and representing the plebs, in R. B. Parker’s words, as “clownish, ineffectual dolts.” Nazis produced the play during the 1930s to portray the evils of democracy and to celebrate Hitler as a conqueror greater than Coriolanus. So powerful was the play’s resonance with Nazis that it was banned in the first years of Allied occupation. On the other side of the political aisle, many productions offer leftish interpretations that highlight the distasteful pride of Coriolanus and present the tribunes as champions of democracy. Eastern European productions in the 1930s turned the plebs and tribunes into heroes and condemned Martius as a tyrant. Bertold Brecht’s unfinished adaptation thoroughly reinvented the story. Instead of being fearful and demoralized by Martius’ attack on Rome, for example, the tribunes organize the plebs into a defense force so fearsome that Martius withdraws of his own accord.

Each of these political interpretations can find a warrant in the text. “What’s the matter, you dissentious rogues, / That, rubbing the poor itch of your opinion, / make yourselves scabs?” These are Coriolanus’ first words in the play, and they set the tone for his other speeches to the plebs. He condemns them as cowardly hares and geese, complains of their body odor and bad breath, and at his banishment dismisses them as a “common cry of curs.” His politics are profoundly antidemocratic. He wonders at the “double worship” of Rome’s famously mixed political system, a system in which “gentry, title, wisdom / Cannot conclude but by the yea and no / Of general ignorance.” On the other hand, it is difficult not to feel the force of his opinions. Isn’t it in fact better for the wise and informed to make political decisions than to subject them to the veto power of the ignorant and apathetic? Shakespeare does not go out of his way to make the people of Rome attractive: they truly do not know what is good for them—thus demonstrating the cogency of Coriolanus’ assessment. They gleefully banish their erstwhile hero, not stopping for a moment to ask what this will cost them. The tribunes control the plebs and are as contemptuous of the people in their own way as Coriolanus is.

Neither the elitist nor the democratic interpretation, however, gets to the political heart of the play, which is the fundamental political problem of gratitude. Coriolanus explores the relationship of gratitude and political order, or, more accurately, the relationship of ingratitude and political disorder. Ingratitude is a recurring theme in the play. In Act II, an officer discussing Coriolanus’ campaign for consul tells a fellow officer that Coriolanus’ military accomplishments “deserved worthily of his country” and says that “for [the plebs’] tongues to be silent and not confess so much were a kind of ingrateful injury.” In the following scene the “Third Citizen” offers a similar opinion: “If he tell us his noble deeds, we must also tell him our noble acceptances of them. Ingratitude is monstrous, and for the multitude to be ingrateful were to make a monster of the multitude—of the which we being members, should bring ourselves to be monstrous members.” In the event, the plebs prove their ingratitude by banishing Coriolanus, who, at the urging of Aufidius, determines to “pour war / Into the bowels of ungrateful Rome.”

Ingratitude is also observed to be a flaw in Coriolanus. When his general Cominius commends his action at Corioli, Coriolanus responds that he cannot bear to be praised, and Cominius points out the defect lurking beneath this apparent humility: “Too modest are you, / More cruel to your good report than grateful / To us that give you truly.” It is also clear that Coriolanus has no appreciation of the plebs who make up the Rome that he claims to protect.

Early in the play, the patrician Menenius tells the plebs the parable of the stomach, in which all the organs of the body rebel against the stomach because, though “idle and inactive,” it gets the first share of all food. Deliberately and gravely and “with a kind of smile,” the stomach explains to the body parts, “True it is . . . / That I receive the general food at first . . . / But, if you do remember, / I send it through the rivers of your blood, / Even to the court, the heart, to the seat o’ the brain; / And, through the cranks and offices of man, / The strongest nerves and small inferior veins / From me receive their natural competency / Whereby they live.” Throughout the play, Menenius’ parable stands as an ideal by which Rome should be judgedby its standard, Rome is weighed and found wanting. Far from functioning as distinct but equally necessary organs of a body, the patricians and plebs hold each other in mutual suspicion, forgetful of their interdependence. Forgetfulness breeds ingratitude; ingratitude breeds faction; and faction leads to civil war.

This emphasis on gratitude is characteristic of Shakespeare’s Roman plays. As Clifford Ronan puts it in his fascinating study of early modern dramas set in ancient Rome, “this theme is not at the heart of most Tudor-Stuart tragedies with Christian settings, even if Macbeth is a striking exception.” Rather, “most studies of ingratitude—lack of gracious acceptance—are to be found in tragedies with a pagan setting: in other words, beyond the customary sphere of gratia.” Though “Roman dramas constitute 30 percent of Shakespeare’s oeuvre . . . concordances suggest that these five plays and Timon contain fully 60 percent of the dramatist’s four dozen uses of words like ingrate, ungrateful, and ingratitude.” Ronan concludes that “Shakespeare and his fellow dramatists seem to have viewed the ancient world, particularly Rome, as stained with a cruel pride—self-interested, ungenerous, contentious, murderous.” “Ingratitude is monstrous,” and Rome, outside the realm of gratia, turns into a grotesque distortion of a body politic.

Shakespeare thus dramatizes the Augustinian perspective most recently articulated by Oliver O’Donovan—namely, that “within every political society there occurs, implicitly, an act of worship of divine rule.” Political society is constituted by an act of worship—in the case of Shakespeare, an act of Eucharist, an act of mutual thanksgiving. And, from this angle, Coriolanus offers a deeper challenge to contemporary political life than has been recognized by interpreters of the play on either the left or the right. The foundation of all political order is gratia. That is the lesson of the play. It is an especially important lesson for us, who live at a time when discontent and complaint dominate public discourse. For Shakespeare, ingratitude is not merely a private moral flaw; it also represents a profoundly dangerous fraying of our political life. For we, too, stand condemned by Menenius’ parable.

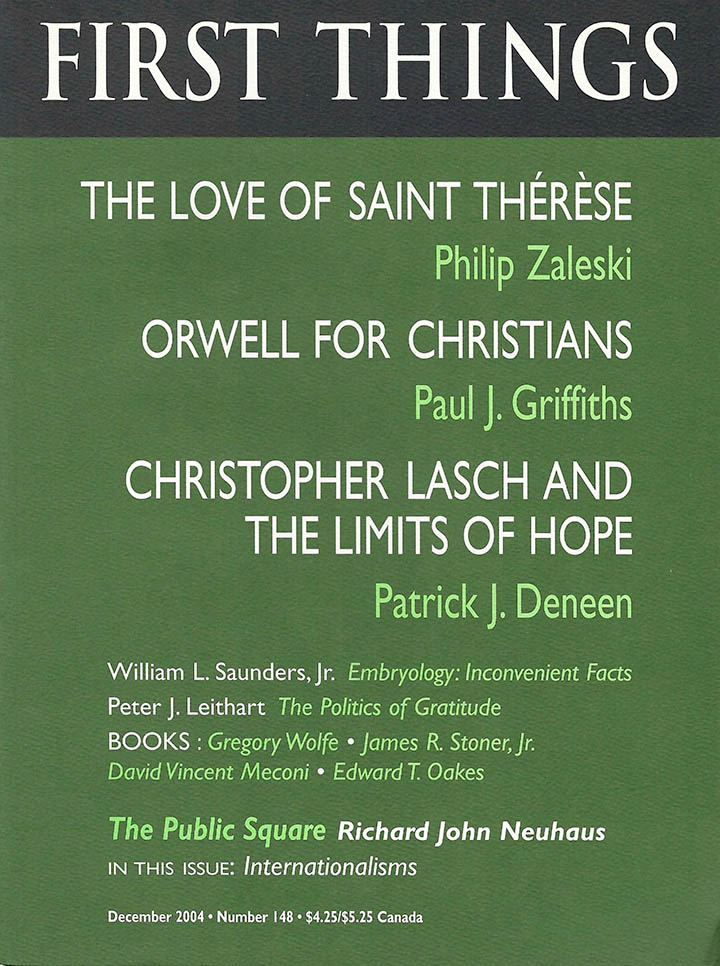

Peter J. Leithart is Senior Fellow of Theology and Literature at New St. Andrews College in Moscow, Idaho, and pastor of Trinity Reformed Church in Moscow.

Uncovering the Real Melania

Melania, Brett Ratner’s documentary following the first lady of 2017–2020 around as she gets ready to become…

The Evangelical Elite Gap (ft. Aaron Renn)

In this episode, Aaron Renn joins R. R. Reno on The Editor’s Desk to talk about his…

Don Lemon Gets the First Amendment Wrong

Don Lemon was arrested last week and charged with conspiracy against religious freedom. On January 18, an…