Growing up a Catholic boy in suburban South Jersey, I knew my share of priests. They were good and holy men doing good and holy work. Yet none of them were imposing figures. And it seemed, nestled as I was among the shopping malls and the subdivisions, that the priesthood was, in the Christian sense, ordinary: Priests saved our souls but were powerless to save our culture, which, it was clear to even a child, was in desperate need of saving.

Of course I learned that the Catholic world was chock-a-block with intellectuals, from Augustine to Chesterton and back again. And I knew that my young pope was a historically formidable man. Yet these great minds seemed remote and unreal”ghostly figures from books or a flickering apparition on the evening news.

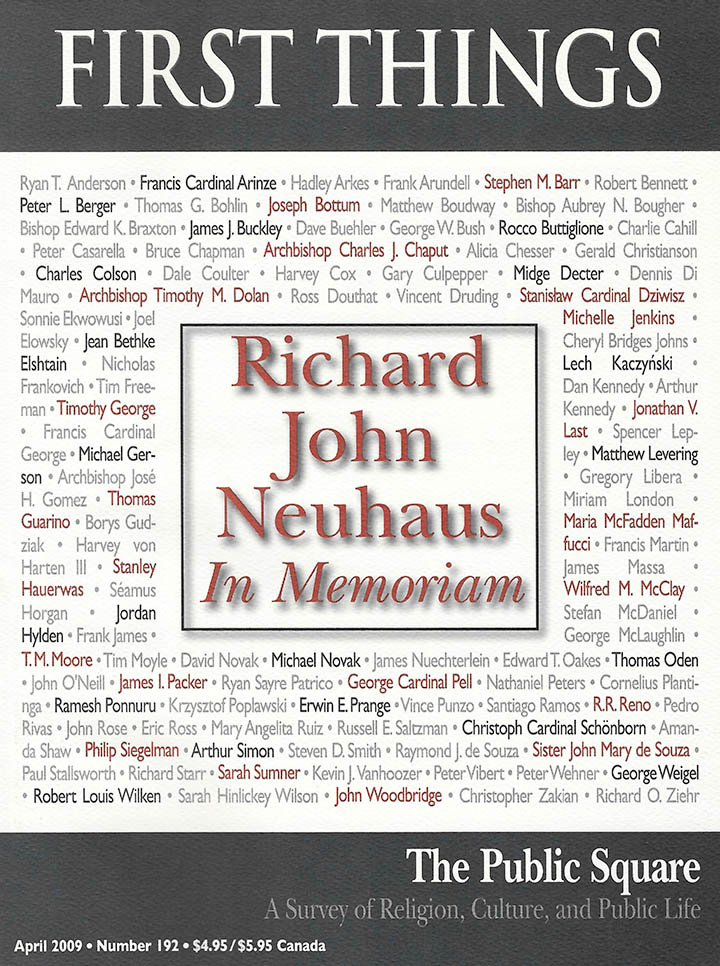

And then I read Fr. Neuhaus. I first stumbled onto “The Public Square” in 1997, shortly out of college, when I was answering phones for the Weekly Standard . I wanted to write, without really knowing how or why. My managing editor told me that I should be reading First Things . So I did. And over the years Fr. Neuhaus’ writings became a kind of personal Strunk and White”a gentle, careful guide on how to write and approach the world of ideas.

One of his great talents was mixing sternness with wit. Describing a particularly silly bioethicist, Fr. Neuhaus wrote, “He reminds one of the undergraduate who, upon reading a little Nietzsche, looks over the abyss into nothingness and exclaims, ‘Wow. That’s cool.’” In another column, he recounted a moment from an interview: “An eager young thing with a national paper was interviewing me about yet another instance of political corruption. ‘Is this something new?’ she asked. ‘No,’ I said, ‘it’s been around ever since that unfortunate afternoon in the garden.’ There was a long pause and then she asked, ‘What garden was that?’ It was touching.”

Sternness is a great writerly virtue and Fr. Neuhaus’ mind was made of awfully stern stuff. But he was never a scold. And his sternness was everywhere commingled with charity. To argue in good faith, to criticize with grace, to demolish without malice”every writer should aspire to such heights. It was Fr. Neuhaus who showed me that it was possible to be both an intellectual and opposed to the murder of babies. I had grown up thinking Catholics were supposed to apologize for their faith in polite company, but Fr. Neuhaus proved that priests could hold their own with the New Yorker crowd.

Over the course of a decade, I admired Fr. Neuhaus from afar. He became one of my most beloved priests and writing heroes. In 2005 Jody Bottum asked me to write a piece for First Things . It was a thrill, like going to one of those baseball fantasy camps where they let you take batting practice with Hall of Famers. I never interacted with Fr. Neuhaus, but was more relieved than disappointed because, as a rule, you should never meet your heroes.

Last September I was in New York working on a story. My interviews finished early and on a lark I called Jody to grab a drink. He asked me to meet him at the First Things office, and when I arrived the staff was shuffling out of an editorial meeting. And there Fr. Neuhaus was. Taller than I had imagined him. And thicker, more solid. Jody introduced us and then stepped away to take a phone call, leaving the two of us alone.

Fr. Neuhaus was gracious and sweet. He told me that he enjoyed the piece I wrote for him. I can’t imagine he really remembered the article”I say this as a judgment on my essay, not on his memory. Even so, that kindness meant quite a lot to me; it is something I will never forget. All Catholics are bound to one another, both spatially and temporally. We are bound to each other here, today. And we are bound to the saints, to the dead, throughout time. I knew him very little, but it is a joy to be bound, still, to Fr. Neuhaus.