Some years ago I was leading a summer study tour in Oxford, England, during which as a matter of course—we were from Wheaton College, after all—we paid a visit to Magdalen College, the longtime academic home of C.S. Lewis. The dean of divinity, as Magdalen terms its chaplain, was gracious and welcoming and gave us an informative tour that concluded in the chapel with Morning Prayer. It was lovely in every way, but then at the end something unusual happened. The dean, instead of pronouncing the traditional benediction, began to recite the concluding paragraph of the final adventure in Narnia, The Last Battle: “And as He spoke He no longer looked to them like a lion. . . .”

I was reminded recently of the feelings I had on that occasion. It happened when I picked up The Green Bible. What is The Green Bible? Let the project’s website speak for itself:

The Green Bible includes

the following distinctive features:

—Green-letter edition: Verses and passages that speak

to God’s care for creation highlighted in green

—Contributions by Brian McLaren, Matthew Sleeth,

N.T. Wright, Desmond Tutu, and many others

—A green Bible index and personal study guide

Recycled paper, using soy-based ink with a cotton/linen cover

And there’s more! Other featured luminaries include John Paul II—strange that he wasn’t among the headliners (beaten out by Matthew Sleeth)—and St. Francis of Assisi and Wendell Berry, whose poems serve as epigraphs. Plus, there’s an anthology of “Teachings on Creation Through the Ages” that takes us from Clement of Rome to Rick of Saddleback.

Now, before I try to account for my discomfort, I wish it known that my family owns only one car (a six-year-old, four-cylinder Subaru), lives in a house with only one bathroom, and recycles fanatically. I walk to and from work most days and fly rarely. My carbon footprint is perhaps one ten-thousandth the size of Al Gore’s. Moreover—and if this does not confirm my bona fides nothing will—I am even now writing a book called The Gospel of the Trees. If you’re looking for someone greener than me, your only options are the Incredible Hulk and Kermit the Frog.

For that matter, The Green Bible has the great merit of treating a theme that is actually in Scripture. The quotation from Romans 8 on the project’s homepage—“For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the children of God; for the creation was subjected to futility, not of its own will but by the will of the one who subjected it, in hope that the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and will obtain the freedom of the glory of the children of God”—really is central to the biblical picture of redemption and really has been neglected in both theory and practice. And I may also affirm my nearly boundless admiration not just for John Paul II, St. Francis, and Wendell Berry but for the claims they make in these pages.

But all that said, The Green Bible makes me distinctly uncomfortable, just as the dean of divinity did when he invoked dear old C.S. Lewis at the conclusion of Morning Prayer. Lewis is indeed dear to me and to millions of others, but admiration of Lewis is not a prerequisite for participating in the rites of the Church. One could believe that Lewis was a theologically idiotic, reactionary old misogynist who couldn’t write his way out of a wet paper bag, whose Narnia tales are a disgraceful blight on the landscape of children’s literature, whose Aslan is a blasphemous parody of Our Lord, and—believing all that—one could still be a faithful Christian, even a devoted Anglican. To include Lewis’ words in worship, as part of the liturgy itself, is to suggest that those words deserve the same reverence that we grant to the Book of Common Prayer and perhaps—given the usual source of liturgical benedictions—Scripture itself.

Now, if the dean had given a homily and in that homily had quoted Lewis, I would have no cause for complaint. Nor, I believe, would the person who loathes Lewis. That person would surely acknowledge (even if wincing while doing so) that preachers, in attempting to interpret Scripture and guide the faithful, are free to draw on a variety of resources to make their points, and that such attempts will not always please everyone. Likewise, a collection of the essays that preface The Green Bible, coupled perhaps with an anthology of relevant portions of Scripture, would surely have been a useful and valuable thing. But subjecting the whole of Scripture to one agenda—enfolding it in the single adjective green—is, I think, an ill-judged strategy for pursuing a worthwhile goal.

Still more ill judged is the over-egging of the rhetorical pudding. The project website tells us that “with over 1,000 references to the earth in the Bible, compared to 490 references to heaven and 530 references to love, the Bible carries a powerful message for the earth.” I am not sure what to make of this argumentum ad arithmeticum, unless the point is that the earth is approximately 1.88 times more important to God than love and 2.04 times more important than heaven. Based on my own research into this topic and following the same method, I am prepared to say that the earth is 7.04 times more important to God than donkeys (which are mentioned 142 times in the Bible).

The Green Bible presents us with a curious kind of natural theology: We start with things we know to be true from trusted sources—Al Gore, perhaps?—and then we turn to Scripture to measure it against those preexisting and reliable authorities. And what a relief to discover that God is green. Because we already know that it’s good to be green—what we didn’t know is whether God measures up to that standard.

The essays in The Green Bible teach more or less the same message in varying ways. There’s a great deal of overlap to them, and several could easily be discarded, though that would compromise the ecumenical message: We got Catholics, evangelicals, mainliners, Jews, the whole shebang. That message is built around three doctrines: creation (God made the world and declared it good), stewardship (God gave us the responsibility to care for that creation), and restoration (God’s plan is to restore the creation).

Everything else is said to follow from these three essential points. For example, “All the elements of Creation . . . are interdependent” (says the unsigned preface) “in such a way that our actions can have repercussions for creatures we will never see.” And thus we must “evaluate our personal consumption and . . . become free of the idea that our worth and fulfillment are wrapped up in our possessions,” as the essay by Gordon Aeschliman puts it.

Moreover, “the poor and vulnerable are members of God’s family and are the most severely affected” by environmental disturbances created by other human beings, especially the wealthy, as Archbishop Desmond Tutu claims. This is repeated so frequently, by so many commentators, that it often seems that being green is a secondary good, something we should practice primarily because it helps the poor, with benefits to the earth being a kind of bonus. I am not complaining about this merging of values—it is right to note that Scripture often presents us with networks of virtues and mutually reinforcing practices. But the confluence does raise the question of why this is a Green Bible rather than, say, a Justice Bible. Could it be that greenness is a sexier commodity right now than justice or peaceableness?

There is one more step that the essays in The Green Bible often take, a step into the realm of practical specificity and policy recommendations. Throughout the essays are scattered references to everything from ozone depletion to recycling strategies to the effects of American pet shops on the population of parrots in New Guinea—and recommendations of particular courses of action: Aeschliman’s commendation of conservancy strategies, for instance, through which churches purchase endangered land to ensure preservation.

The presence of such policy-oriented commentary raises an interesting question: How do we get from highly general biblical principles to specific policies and practices? For get there we must. The contributors to The Green Bible say over and over again that we must act righteously toward, not just think correctly about, creation, and this is surely true. In fact, almost all of their general principles are surely true, so anodynely beyond question that one wonders why they are worth reasserting at such length. Is anyone really going to say, “No, I think my value as a Christian and a human being is determined by the number of possessions I have”? Or, “I see no biblical mandate for caring for the poor”? The principles are tiresomely belabored, but the specific policy recommendations don’t follow straightforwardly from the principles. How do we get from “We must be good stewards of creation” to “Our church needs to invest in the Eden Conservancy Project”?

It seems to me that one way we get there is through deep and serious empirical study, so that we can determine with some reasonable degree of confidence whether the Eden Conservancy Project—and the general conservation strategy it represents—really is a good way for those of us who want to care for God’s creation to invest our resources.

But, of course, any answer to such empirical questions will depend on how well we have formulated the questions—how well we understand our goals and desires, how well we understand our concepts of care and conservation. This is another way of saying that we also must get from general biblical principles or commandments to specific practices through theology.

Alas, there is precious little actual theology going on in The Green Bible’s essays, and some of what goes on is, shall we say, inadvertent: The preface tells us that “God and Jesus interact with, care for, and are intimately involved with all of creation.” (God and Jesus? Remarkable. But only the two of them?) N.T. Wright’s largely exegetical essay “Jesus Is Coming—Plant a Tree!” is surely the most theologically deep and intellectually provocative item in the bunch. Even the address by John Paul II is theologically thin, largely because it was given to commemorate the World Day of Peace in 1990 and was therefore directed to a general audience.

But even if the theology here were rich and deep and uniformly brilliant, I would still be concerned about a Bible with so much ancillary material on a single subject. This strategy too easily conflates a particular agenda and the whole biblical message. If God is green, then are the green also godly? The essays in The Green Bible don’t do anything to discourage that line of thought.

But what about the text of Scripture itself? This is after all a “green-letter edition,” in which “verses and passages that speak to God’s care for creation” are “highlighted in green.” I cannot help being reminded of a gift I received about thirty years ago, the Salem Kirban Bible. Salem Kirban was a biblical-prophecy guru who flourished in the 1970s—think of a minor-league Hal Lindsey—who produced a Bible in which every passage of Scripture relating to the end times was highlighted, magnified, commented on, and surrounded by illustrations. Meanwhile the rest of Scripture was consigned to unreadably small type, as befitted the adiaphora contained within it.

Well, The Green Bible is not quite so bad: The text may be green or black, but it’s all the same size. Still, the greenness, along with the “Green Bible Trail Guide” at the back of the book, does say pretty clearly, “This is the stuff that really matters,” which is another way of saying, “That other, nonemphasized stuff doesn’t matter as much.” And in that sense this project isn’t all that different from the Salem Kirban Bible. Green is the new dispensationalism, I suppose.

It may be asked at this point whether I also protest the existence of red-letter Bibles, with their singling out of the words of Jesus, as though those have greater authority than the rest of the Bible. Well, to be truthful, I do, rather, and therefore I’m not sanguine about Tony Campolo’s “red-letter Christian” movement, with its claim to give particular emphasis to the (supposedly neglected) words of Jesus. But Campolo at least makes the theologically responsible argument that “you can only understand the rest of the Bible when you read it from the perspective provided by Christ.”

Reading the Bible “from the perspective provided by” the green letters doesn’t work that way. For Christians, Jesus Christ is not only the Way, the Truth, and the Life. He is also, as St. Paul says, the end of the Law and its fulfillment: “He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things were created through him and for him.” Nothing of the kind can be said for the green-letter themes. Christ leads you to everything else; greenness does not. And the green lettering invites us to separate one theme from others, extracting it from the larger story of which it is a part.

Is it fair to ask The Green Bible to make all these theological connections? Yes, because it’s a complete Bible. The green lettering, the prefatory essays, and the concluding study guide collectively suggest that this one theme is the interpretative key to all of Scripture. And that’s simply not a sustainable claim.

This would be true even if the green-lettered verses presented a clear and consistent message, but they do not. Many of them say what you might expect them to say, but others can be irrelevant or disturbing. The irrelevant ones come when the editors are stretching too far to make a point, something that happens especially in the gospels, presumably from a desire to enlist Jesus in the cause. It’s hard to think of any other reason why this passage would be printed in green: “In the morning, when it was still very dark, he got up and went out to a deserted place, where he prayed.” And what precisely is green about “Do not judge, and you will not be judged; do not condemn, and you will not be condemned”?

The disturbing selections—which, to give the editors full credit, are faithfully green-lettered—suggest that the whole idea of “God’s care for creation” is far more complex than our usual pieties indicate. What are we to do with, for instance, these words from Ezekiel? “Mortal, set your face towards the south, preach against the south, and prophesy against the forest land in the Negeb; say to the forest of the Negeb, Hear the word of the Lord: Thus says the Lord God, I will kindle a fire in you, and it shall devour every green tree in you, and every dry tree; the blazing fire shall not be quenched, and all faces from south to north shall be scorched by it.”

We are perhaps not as awed as the first audience of the Book of Job might have been by God’s invocation of Leviathan and Behemoth—we can see such creatures in the zoo—but this picture of God as the agent of pure destruction, as the divine arsonist, is surely unsettling. Even Jesus curses and blights a fig tree, and, while he may have done so to make a point about human beings, it was the fig tree that paid the price.

Some will argue that the Book of Revelation promises the complete destruction of this world and its replacement by “a new heaven and a new earth.” I am not inclined to that view; I tend to agree with N.T. Wright that the vision points to a moment when the new creation is made “not ex nihilo, but ex vetere, not out of nothing, but out of the old one, the existing one,” just as the resurrected body of Jesus is not a brand-new body but his old one glorified.

Even so, we must face the fact that God’s interaction with his creation is not always constructive and restorative but is often shockingly destructive. It is true that the destruction always precedes some kind of renewal, but it is destruction all the same, and while we can come up with comforting scenarios in which we do the same kind of thing—controlled burns in forest management and farming, for instance—it would be best not to allegorize too readily. God loves his creation, but he deals with it in ways that, to us, are sometimes indistinguishable from hatred. As he deals with us.

Our explanations for all this often come perilously close to explaining it away. I would be inclined to give The Green Bible only to those who have passed a detailed examination on the book of Job, about the end of which G.K. Chesterton wisely said, “The riddles of God are more satisfying than the solutions of man.”

I would guess that The Green Bible is addressed to two constituencies. First, committed environmentalists, or those at least deeply attracted to it, who view Christianity with skepticism; people who might become more open to Christianity if they come to believe that God is green. And second, Christians who would like to find some biblical warrant for their attraction to environmental issues. Members of each group could benefit from this book, but only if they are able to maintain a critical distance from some of its claims, implicit and explicit.

How many such people are there? I couldn’t say. But it is worth noting that, in a recent Pew Forum survey of the political priorities of white evangelicals, the environment came in next-to-last in importance. (The only lower priority among the thirteen on the list was gay marriage; the economy led the pack.) Results for “white non-Hispanic Catholics” were roughly similar.

Meanwhile, in Lake Superior State University’s annual “List of Words to Be Banished from the Queen’s English for Misuse, Overuse, and General Uselessness”—tabulated from readers’ submissions—green has just come in first. “I’m all for being environmentally responsible, but this green needs to be nipped in the bud,” says Valerie Gilson of Gales Ferry, Connecticut, employing an apt idiom. The more vigorous Ed Hardiman of Bristow, Virginia, says, “If I see one more corporation declare itself green, I’m going to start burning tires in my backyard.”

So it’s possible that The Green Bible is actually poised between two audiences: one unready for the message, one already tired of it. Meanwhile, the creation, still “subjected to futility,” continues to “wait with eager longing” to be “set free from its bondage to decay.” And we, even at our best, still strive to know what it means to hold this world in stewardship. Creation remains always too large for us, too abstract. What’s real is this furrow of black soil, that crabapple tree: These we can protect insofar as we see them, touch them, and therefore know them. But no general principle, no notion of greenness, can tell us how to care for what occupies our field of vision this moment, what sifts between our outstretched fingers.

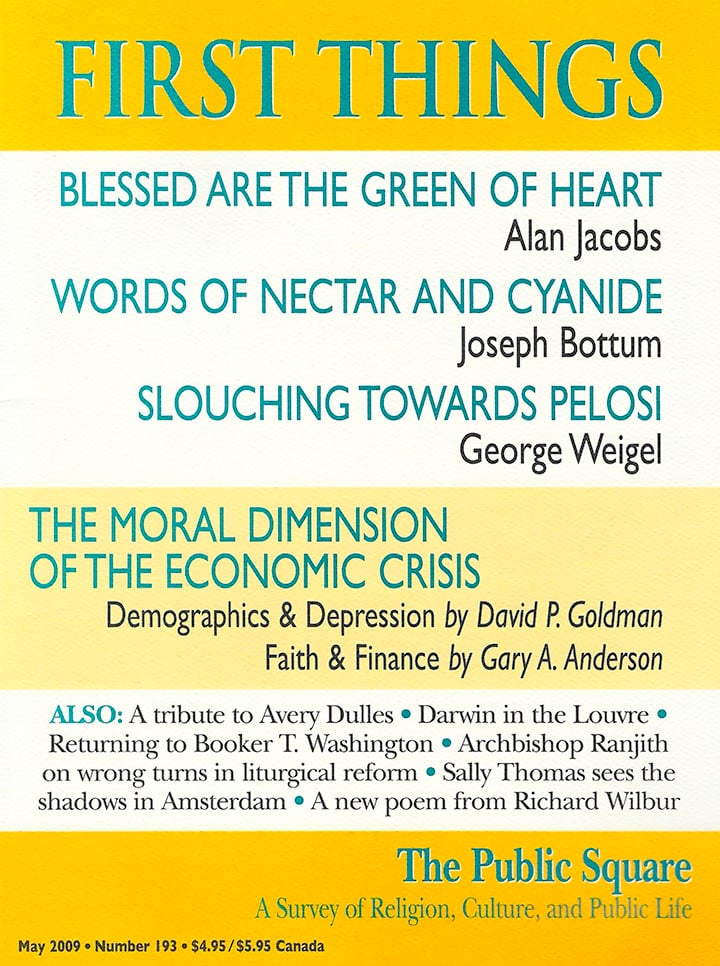

Alan Jacobs is a contributing writer for First Things and a Distinguished Professor of the Humanities in the Honors Program at Baylor University.

Postliberalism and Theology

After my musings about postliberalism went to the press last month (“What Does “Postliberalism” Mean?”, January 2026),…

In the Footsteps of Aeneas

Gian Lorenzo Bernini had only just turned twenty when he finished his sculpture of Aeneas, the mythical…

The Clash Within Western Civilization

The Trump administration’s National Security Strategy (NSS) was released in early December. It generated an unusual amount…