The horror-film genre is multiplying like one of its own monsters, showing six-fold growth over the past decade—turning what used to be a Hollywood curiosity into a mainstream product. Not only the volume of films but their cruelty has increased, with explicit torture now a screen staple.

Why do Americans pay to watch images as revolting as the cinematic imagination can discover? Many things might explain the vast new market for uncanny evil. If you do not believe in God, you will believe in anything, to misquote G.K. Chesterton; and, one might add, if you do not feel God’s presence, you will become desperate to feel anything at all. Terror and horror create at least some kind of feeling. After pornography has jaded the capacity to feel pleasure, what remains is the capacity to feel fear and pain.

But there is a pattern to the highs and lows of the horror genre that may reflect something specific about Hollywood’s feeding of the mood of the United States—something about America’s encounter with truly horrible events, from the Second World War through Vietnam and down to the attacks of September 11, 2001 and the lingering conflict in Iraq. Terror loiters in dark corners just off the public square.

Among all the film genres, horror began as the most alien to America. The iconic examples of the genre in the 1930s required European actors and exotic locales—vampires from central Europe, for example, and zombies from Haiti. The films were noteworthy precisely because they were so unlike the cinematic mainstream: In 1931, the year that Frankenstein and Dracula first appeared, the worldwide film industry managed to make and release 1054 features, of which only seven could be called supernatural thrillers. After retreading the same material for twenty years, Hollywood finally put a stake through the genre’s heart. By 1948, the few horror films being made were the likes of Abbott and Costello encountering Dracula, the Wolfman, and Frankenstein’s monster. Laughing at monsters was emblematically American—and remained so, as when Mel Brooks and Gene Wilder did it, perhaps best of all, in 1974 with Young Frankenstein.

In other words, Hollywood gave us a small run of exotic-origin horror films in the 1930s, all drawn from European fiction: Dracula, Frankenstein, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Picture of Dorian Gray. After the Second World War, however, these nightmares of tormented Europeans were mostly naturalized as sight gags for American adolescents.

And that was how it was supposed to be. The monsters had a different meaning in their Old World provenance. As Heinrich Heine once observed, the witches and kobolds and poltergeister of German folktales are remnants of the old Teutonic nature-religion that went underground with the advent of Christianity. The pagan sees nature as arbitrary and cruel, and the monsters that breed in the pagan imagination personify this cruelty. Removed from their pagan roots and transplanted to America, they became comic rather than uncanny. America was the land of new beginnings and happy endings. The monsters didn’t belong.

Making fun of foreign monsters fit the national mood after the war—a war, after all, in which Americans had encountered for the first time a neopagan foe that wielded horror as an instrument of policy. The existence of horror is, generally, a weakness of Christian civilization, for such civilization stands, finally, as the rejection of the horrors that paganism always accepts and often embraces. How can a good God permit terrible things to happen? Voltaire used the most horrific event of the eighteenth century, the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, to ridicule the idea of a loving God. The neopagans of the twentieth century went Voltaire one better. Rather than wait for natural disaster, they staged scenes of horror greater than the civilized mind could fathom—as though the most effective assault on faith were to commit crimes beyond the imagination of the observer. As Goebbels bragged in a 1943 broadcast, “We will either go down in history as the greatest statesmen of all time, or the greatest criminals.”

The United States would have none of it. After 1946, Hitler had been crushed, and that was that. Americans did not want to think about it anymore. And at the height of the national self-confidence that followed, the horror genre almost disappeared from American film. In 1950, for example, Hollywood managed only four films in the genre, all B-movie filler.

Horror recolonized American culture during the late 1960s. The genre jumped from 2 percent of all films to 6 percent between 1968 and 1972. The homegrown American horror film, moreover, evolved from summer-camp slashers to truly disturbing portrayals of torture and madness. As the online commentator Marco Lanzagorta notes, “a renewed interest in the horror genre” arrived “in the late 1960s, most probably due to the success of sophisticated and revolutionary horror films” in the vein of Night of the Living Dead (George Romero’s 1968 surprise B-movie hit) and Rosemary’s Baby (Roman Polanski’s 1968 major-studio release).

What motivated so many Americans to subject themselves to such torment? Perhaps the explanation is that horror had returned as a subject in American life with Vietnam. U.S. troops were engaged with an enemy that made civilian populations the primary theater of battle, fighting a different and terrible sort of war. The images of civilians burnt by napalm transformed my generation. Until our adolescence—I was already twelve when John F. Kennedy was killed—America’s civic religion was taken for granted. In 1963, my peers and I put our right hands over our hearts when the flag passed; by 1967, we did not flinch at flag burning. Horror over a war in which civilians could not be distinguished from combatants destroyed America’s civic religion, and it was, I suspect, also the beginning of the end of mainline Protestantism.

Long after the fact, Francis Ford Coppola transplanted Joseph Conrad’s tale of horror in the jungle to Vietnam. Compared to what we had seen on television, the 1979 Apocalypse Now seemed trivial, but it gave permanent images to the post-Vietnam national mood: the sense of being lost in a nightmare of pointless and pervasive cruelty.

As data drawn from the Internet Movie Database shows, the horror genre grew from insignificance during the 1950s to 6 percent of all releases by 1972, during the last phase of the Vietnam War. A second spike came in 1988, driven by a bumper crop of sequels to established series (Halloween, Nightmare on Elm Street, Critters, Friday the Thirteenth, and so on).

But what accounts for the six-fold increase in the total number of horror films released since 1999? Subgenres such as erotic horror (mainly centered on vampires) and torture (the Saw series, for example) dig deep into the vulnerabilities of the adolescent psyche. Given the success of these films over the past ten years, the number of Americans traumatizing themselves voluntarily is larger by an order of magnitude than it has ever been before.

There are any number of possible explanations for this phenomenon. What the bare facts show, however, is that moviegoers are now evincing a susceptibility to horror. People watch something in the theater because it resonates with something outside the theater. To see the cinematic representation of horrible things may be frightening, but the viewer knows that it is safe. And the sense of safety we derive from watching make-believe things helps us tolerate the prospect of real things. What in the world today horrifies us the most? The horror that attended the Vietnam War had far-reaching cultural effects even though not a single shot was fired on American territory. All the more so should we expect the attack on the World Trade Center and its aftermath to have such consequences.

Random acts of terror against civilians seem a new and nearly incomprehensible instrument of war to most Americans. That is why they have such military value: The theater of horror has a devastating effect on our morale. The same is true for suicide attacks, which continue on a scale that has no historical precedent. The enemy’s contempt for his own life is, in a sense, even more disturbing than his disregard for ours. Nor should we underestimate the cultural impact of the torture debate. Not only has America considered regularizing an abhorrent practice, but our armed forces have become entangled in countries where torture is a routine and daily matter. Americans do not need to imagine what might be going on in Afghanistan. They can see videos on YouTube of young Muslim women being tortured for minor infractions.

Starting on September 11, 2001, Americans were exposed to an enemy that uses horror as a weapon, as did the Nazis—who never succeeded in perpetrating violence on American soil. In its attempt to engage the countries whence the terrorists issued, America has exposed its young people to cultures in which acts of horror (suicide bombing, torture, and mutilation) have become routine. As long as we insist that there is no fundamental difference between our outlook and theirs—and as long as we take responsibility for the civic outcome in such cultures—their horror becomes ours. In the Second World War, America portrayed its cause as a crusade against the forces of evil. Today we send female soldiers wearing headscarves under their helmets to show cultural sensitivity to the Afghans.

How much damage the souls of Americans have incurred in consequence of this exposure to real horror, we cannot say. But the growing morbidity of America’s imagination as shown in the consumption of cinematic horror suggests we might heed the tagline of Jeff Goldblum’s 1986 remake of Vincent Price’s The Fly , made famous by Christina Ricci in the 1993 spoof Addams Family Values: Be afraid—be very afraid.

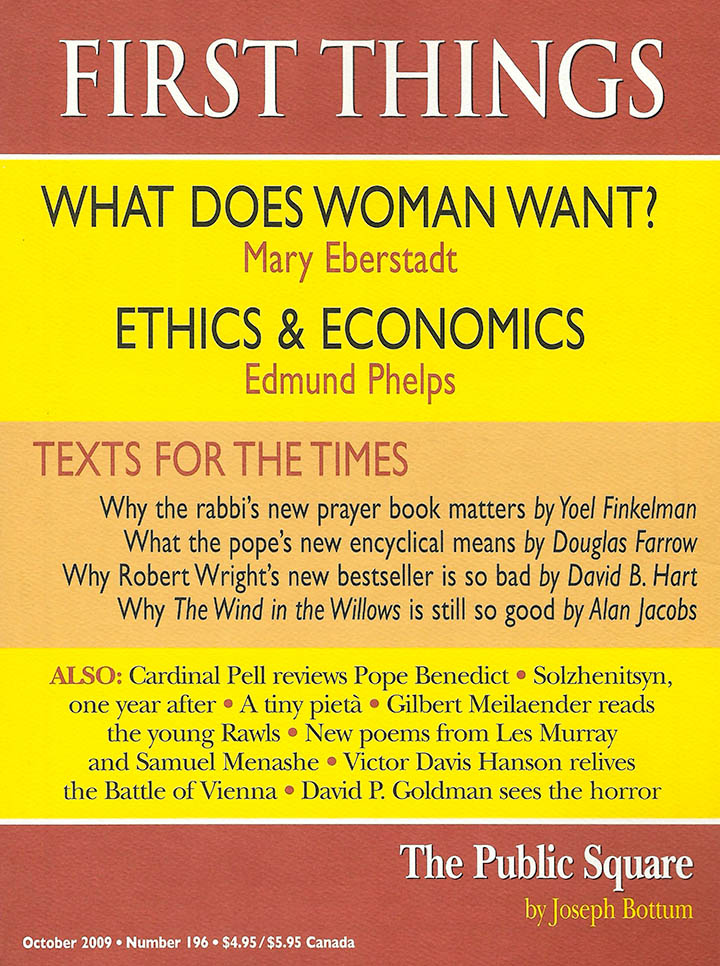

David P. Goldman is associate editor of First Things.

In the Footsteps of Aeneas

Gian Lorenzo Bernini had only just turned twenty when he finished his sculpture of Aeneas, the mythical…

The Clash Within Western Civilization

The Trump administration’s National Security Strategy (NSS) was released in early December. It generated an unusual amount…

Fanning the Flames in Minnesota

A lawyer friend who defends cops in use-of-force cases cautioned me not to draw conclusions about the…