Deep Reform in the 21st-Century Church

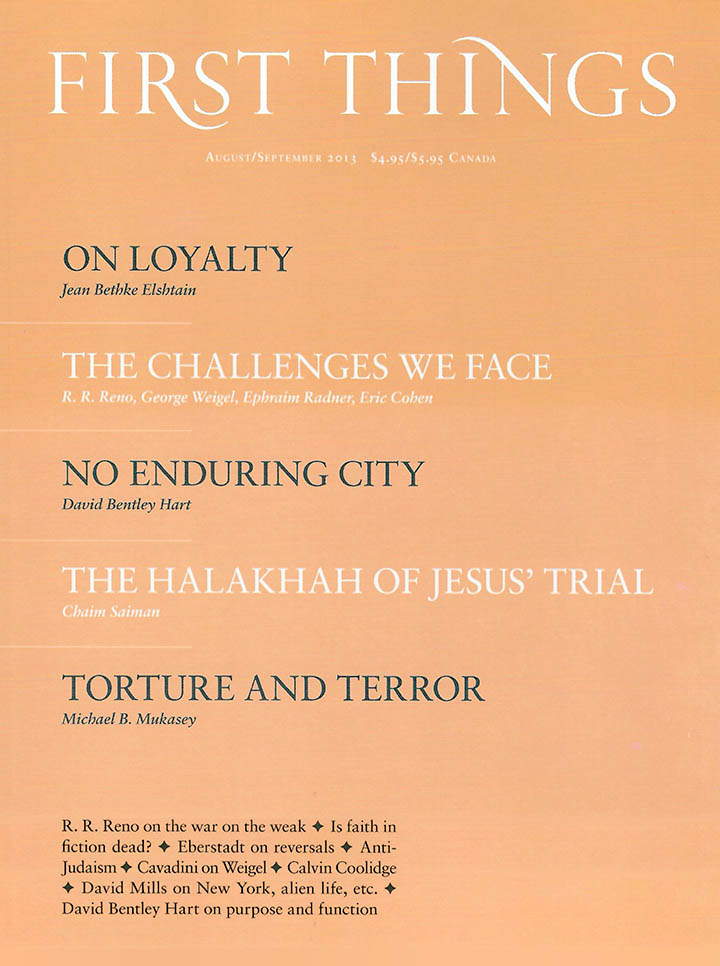

by george weigel

Basic, 304 pages, $27.99

In his bracing though sometimes problematic new book Evangelical Catholicism: Deep Reform in the 21st-Century Church, George Weigel advances a vision for “deep reform” that he calls neither “progressive” nor “traditionalist” but precisely “evangelical.” “Evangelical Catholicism” is heir to a “deep reform” movement begun by Leo XIII—“deep” because a fundamental reform of a centuries-old “Counter-Reformation” model of the Church to one open to engagement with modern culture.

Instead of allowing the Church to retreat in the face of increasing marginalization by the forces of modernity, Leo mobilized the evangelical energy of the Church to affect the ambient culture in ways that were based in the Church’s unique witness to the Gospel. Vatican II was not so much an innovation as a further manifestation of what Leo had already begun.

The twenty-first-century Church will continue true to this reform if its terms of reference become increasingly evangelical, for example, moving from saying “the Church teaches” to “the Gospel reveals” when discussing the faith. Further, “friendship with Jesus Christ” will be the center of Evangelical Catholicism, not reliance on “canonical status” and the predominantly juridical terms in which Counter-Reformation Catholicism defined its identity.

Evangelical Catholicism “begins with meeting and knowing the Lord himself.” Catholic identity is approached “not primarily through the legal question of canonical boundaries, but through the theological reality of different degrees of communion with the Church,” on the analogy of the degrees of communion used to describe the relative closeness or distance remaining between the Catholic Church and separated Christian communions. Members of the Church can also be said to exist in different degrees of communion with the Church according to their adherence to Church teaching and their robust friendship with Jesus.

Weigel argues that the twin criteria of truth and mission, the goal of which is sanctification, are the criteria for the reform of all of the vocations in the Church. Truth and mission both bring their gifts to bear, in a spirit of continuing conversion, on missionary proclamation of the truth, building up a culture conducive to Gospel values. The “deeply reformed” Church becomes an evangelizing presence in the modern world, wherever she finds herself.

There is much to commend in this vision of the Church. If the Catholic reader experiences some feeling of discomfort, the feeling is surely partly due to being called out of the Catholic comfort zone in which one takes one’s religion for granted, as an essentially private affair that places no particularly urgent demands for proclamation of the Gospel in word and deed.

But it is also sometimes hard to distinguish this beneficial discomfort from the worry that, despite Weigel’s disclaimer distinguishing Evangelical Catholicism from Protestant Evangelicalism, the ecclesiology implied in his descriptions of Evangelical Catholicism threatens to leave behind fundamental features of Catholic ecclesiology.

For example: “Evangelical Catholics know that friendship with the Lord Jesus and the communion that arises from that friendship is an anticipation of the City of God in the city of this world.” Despite the echo of Augustinian language, the theological syntax is foreign to the Augustine of the City of God and to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, which invokes his ecclesiology of the totus Christus. The communion of the Church does not arise from personal friendship with the Lord Jesus, but from Christ’s undeserved, atoning love which, mediated by the sacraments, makes the Church. The Church is the bond of communion, whether it is consciously known in a subjective friendship or not.

Weigel’s account of this friendship and its relation to what constitutes the Church is ambiguous. He says it is “found in the Church” and yet insists strongly that “You are a Catholic because you have met the Lord Jesus and entered into a mature friendship with him”which is to say, in evangelically Catholic language, that the sacramental grace of your Baptism, should you have been baptized as an infant, has been made manifest in the pattern of your life.” But the truth is, you are a Catholic because you were baptized and thereby made a member of the one Body, espoused into one flesh with the Bridegroom. There is no amount of subjective friendship that can replace or add anything substantial in comparison with this utter gift. Weigel’s formulation reduces this sacramental bond to something merely legal.

Weigel claims that “evangelical Catholics who adhere to the Gospel? . . . are in fuller communion with evangelical Protestants who affirm classic Christian orthodoxy” than they are with prominent dissident (but not excommunicated) Catholic theologians. But surely it is precisely “classic” Catholic orthodoxy on the Church that is the fundamental difference separating Evangelical Protestants and Catholics.

Weigel’s claim is intended to illustrate his idea of “degrees of communion” within the Church, an idea not referenced to any magisterial source. If thematized consistently, it would mean that the blood of Christ is not really efficacious unto communion, but it is rather the purity and virtue of core individual members of the Church that form the real bonds of communion.

Weigel seems to recognize, with Augustine, that the Church is a mixed body of wheat and tares. He says that deep reform “is not a matter of preemptively burning out the weeds, although it will involve some radical clarification of what are in fact weeds.” But Augustine’s point is that you cannot now clarify this at all. This does not mean that we cannot identify false teaching and bad behavior and lovingly exhort or require correction, but it does mean that the identity of the Church is radically sacramental, not based on advance knowledge of eschatological clarity.

It is significant that Weigel claims Dei Verbum, not Lumen Gentium , is “the key Vatican II document for the deep reform of the Catholic Church.” He never mentions the doctrine, prominent in Lumen Gentium and emphatically repeated in the Catechism, that the Church is the sacrament of communion with God and of unity among human beings.

In fact, this is its “first purpose.” The Church can be this because she is born not primarily from our works, confession, or conduct, but because she is “born primarily of Christ’s total self-giving for our salvation anticipated in the institution of the Eucharist and fulfilled on the cross,” and she comes forth from his side as his Bride, joined to him in one flesh as one Body.

Weigel substitutes for this teaching the doctrine of Christ as the primordial sacrament of the human encounter with God, an expression not used in the Catechism. He uses it, in effect, to replace the doctrine of the Church as sacrament: “Evangelical Catholicism begins with meeting and knowing the Lord himself, the primordial Sacrament of the human encounter with God.”

Repeating Schillebeeckx’ formula without any corresponding emphasis on the sacramental nature of the Church tends to separate Christ from the Church, despite Weigel’s best intentions, replacing the sacramental nature of the Church in the world with “the Lord himself,” who is thus ambiguously located relative to his own Body. The intimate one-flesh union of Christ with his Spouse is vitiated. The “Lord himself” becomes ambivalently available for subjective experiences of personal friendship.

Weigel comments, “The joy of being in the presence of the Lord is the sustaining dynamic of the communion, the unique form of human community, that is the Church.” But is that really true? The sustaining dynamic of the communion that is the Church is the all-surpassing sacrifice of Christ. Establishing Christ as the “primordial sacrament” without any evident relationship to the Church as sacrament leaves the Church as simply a “unique form of human community.”

Ironically, for a cultural critic, this weakens the perspective that the Church can bring to bear on all of the absolutizing claims of the kingdoms of this world. For it is only a community that is not formed on the basis of claims of human purity, achievement, or excellence, however unique, that can mediate perspective, simply by its very presence in the world, on those that are.

To be fair, Weigel does not develop the ecclesiology drawn above. Yet it is not clearly blocked, and it would seem the author’s responsibility to do so. Otherwise, the “deep reform” of the Catholic Church will, despite the author’s laudable goals, turn out to be not merely a reform, but a rejection.

That being said, one is hard pressed not to admire the contagious spirit of evangelical zeal that fills Weigel’s call for specific reforms, and perhaps the textual infusion of this spirit in the reader is the major contribution of this book. Weigel first argues that the reform of the episcopate, and of overly bureaucratized episcopal conferences with little mechanism for fraternal correction or evangelical response, is the most pressing reform needed.

The sexual abuse scandal was essentially a “grave crisis of episcopal malfeasance and misgovernance” and “the key” to reform involves a change in criteria by which candidates for bishops are identified. He is right that we need to have new criteria for electing bishops and a new process that includes broader consultation, rectifying “the absence of any serious lay input.” He notes the irony that Karol Wojtyla, only thirty-eight when ordained a bishop, and known more for his preaching, teaching, and friendships with layfolk than for his oiling of the gears of episcopal advancement, would not have been likely to have been selected today.

A reform of the priesthood away from clericalism is the next desideratum, with reforms in seminary education, especially in the teaching of Scripture. Clericalism substitutes for effectiveness. A pedagogy that relies too exclusively on historico-critical methodologies, without corresponding, equally sophisticated attention to understanding how Scripture is the Word of God, undermines confidence in Scripture as the Word of God, contributing to lackluster, moralizing preaching that does not know how to reach into the spiritual depths of the text. The teaching of Dei Verbum, which called both for historical contextualization and contextualization in the “analogy of faith,” is left largely untried.

Also, reforms of liturgical styles that over-emphasize the personality of the celebrant, and of hymnody that trivializes the doctrines it sings, are clearly desirable. The continuing reform of the papacy such that the “evangelical” modes of popes from John XXIII to Benedict XVI continue to displace the model of “CEO of Catholic Church Inc.” is surely a desideratum, as Weigel suggests. So is a reform of the College of Cardinals making it more globally representative, and a reform of the Roman Curia, source of recent scandals and safe haven for professional incompetence.

Oh—I was conveniently about to forget what cuts closest to myself—the laity are by no means exempted from evangelical reform, especially where the practice of the faith requires a countercultural witness that demands us all to step out of our Counter-Reformation Catholic comfort zones and take a greater responsibility for evangelization in the home, family, work, society, and public square.

John Cavadini is professor of theology at the University of Notre Dame.

The Evangelical Elite Gap (ft. Aaron Renn)

In this episode, Aaron Renn joins R. R. Reno on The Editor’s Desk to talk about his…

Don Lemon Gets the First Amendment Wrong

Don Lemon was arrested last week and charged with conspiracy against religious freedom. On January 18, an…

Goodbye, Childless Elites

The U.S. birthrate has declined to record lows in recent years, well below population replacement rates. So…