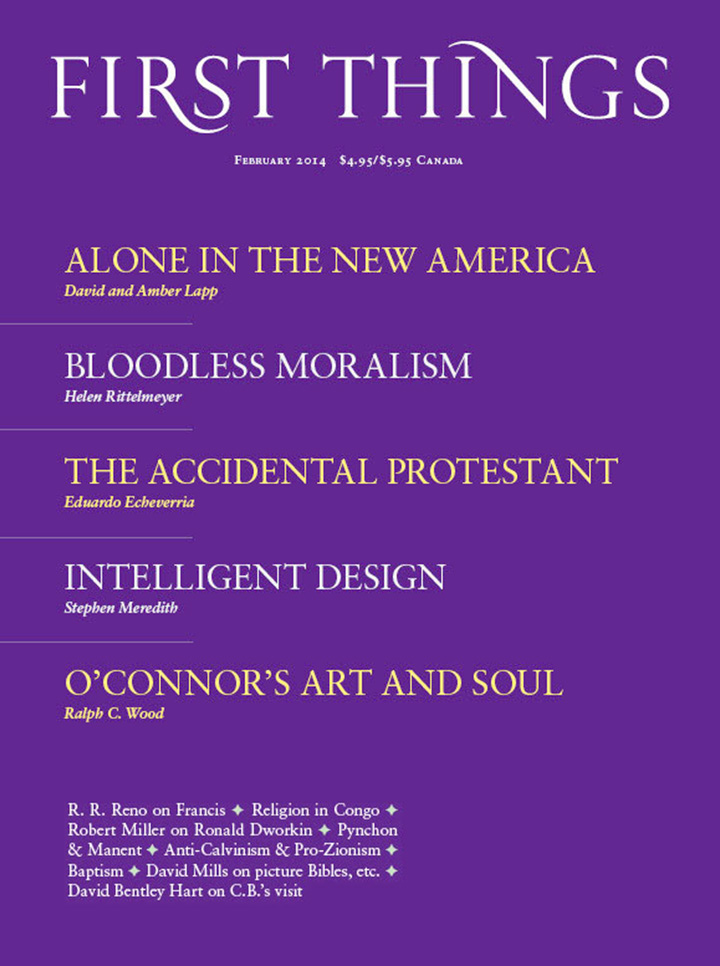

A Prayer Journal

farrar, straus and giroux, 112 pages, $18

O’Connor was only twenty-one when she recorded this humorous but candid confession. A year earlier, she had left her home in Milledgeville, Georgia, to attend Paul Engle’s famous Writer’s Workshop at the University of Iowa. There she was quickly to emerge as the finest student in the program. This journal, ably introduced by her friend and biographer, William Sessions, was kept spasmodically for twenty months during her time there, in 1946 and 1947.

It is doubtful whether these spare petitions, penned in a cheap notebook and offered mainly for greater faith in the face of persistent doubt, would have been published if O’Connor had not become one of the most important Christian authors this country has yet produced. Yet like the slight things left by other major writers, these brief prayers and ruminations cast fresh light on O’Connor’s literary vision as it was just beginning to develop.

Much too often, she admits, she sees herself not as she truly is but as she falsely wants and would like to be. Her missal and rosary and memorized prayers are often unavailing, her contrition confessedly imperfect. She can lament her sins against others more readily than the evils that harm God more directly. Self-deception is the persistent lure, and it stifles the spirit: “My mind is in a little box, dear God, down inside other boxes inside other boxes and on and on. There is very little air in my box. Dear God, please give me as much air as it is not presumptuous to ask for.”

Failings of the soul, in her case, produce failures in art. Unless she can order her loves to the love of God, self-regard will occlude the light of inspiration:

Dear God, I cannot love Thee the way I want to. You are the slim crescent of a moon that I see and my self is the earth’s shadow that keeps me from seeing all the moon. The crescent is very beautiful and perhaps that is all one like I am should or could see; but what I am afraid of, dear God, is that my self shadow will grow so large that it blocks the whole moon, and that I will judge myself by the shadow that is nothing.

Her last entry is as bleak as Mother Teresa’s own acknowledgments of spiritual darkness and emptiness: “My thoughts are so far away from God. He might as well not have made me,” she begins her final entry. Then the last words recorded there: “There is nothing left to say of me.”

O’Connor’s youthful prayers are nonetheless bracing rather than dispiriting. Some of them are uncannily prophetic of the suffering that would overtake her in just three years, when she would be stricken by lupus erythematosus and then would die at age thirty-nine in 1964. “Dear Lord, please make me want You. It would be the greatest bliss. Not just to want You when I think about You but to want You all the time, to think about You all the time, to have the want driving in me, to have it like a cancer in me. It would kill me like a cancer and that would be the Fulfillment.”

O’Connor regarded both her life and her art as sacrifices offered not only in gratitude for her own salvation but also in expiation for the sins of a world that remains dead to the presence of God. Hence her petition for the grace to discern “the bareness and the misery of the places where You are not adored but desecrated.”

Far from being self-righteous toward such living corpses, she asks God to make her a latter-day ascetic who atones for their deadly self-indulgence. Only then would her art and life embody the enormous risk and cost: “The intellectual & artistic delights that God gives us are visions & like visions we pay for them; & the thirst for the vision doesn’t necessarily carry with it a thirst for the attendant suffering. Looking back I have suffered, not my share, but enough to call it that but there’s a terrible balance due. Dear God please send me Your Grace.”

In her most poignant pleas, O’Connor asks that she might not become a mediocre writer, even though she vows to submit to such a middling fate if this is God’s scourge for her lack of discipline. “I am too lazy to despair. Please don’t visit me with it, dear Lord I would be so miserable.”

The sin of sloth resides in a flaccidity of will and desire. Faith, like hope, requires hunger and receptivity. O’Connor frankly confesses that “God is feeding me and what I’m praying for is an appetite.”

O’Connor prays above all for mastery of her craft, so that her Christian vision and her art might constitute a seamless whole: “Writing is dead. Art is dead, dead by nature . . . . Oh Lord please make this dead desire living.” Any division between form and matter is a defilement of both. And their inseparability was made all the more difficult because she sought to write about natural things as they have been properly supernaturalized.

To make nature and grace fully cohere in fiction is a drastically difficult work. It requires nothing less than the aesthetic equivalent of imitating the Christ who is at once truly God and truly human, distinct in natures but indivisibly one: “To maintain any thread in the novel there must be a view of the world behind it & the most important single item under this view of [the] world is conception of love—divine, natural, & perverted.”

The road to such love is the way to the human Golgotha that brings no earthly finish: “It will be a life struggle with no consummation. When something is finished it cannot be possessed. Nothing can be possessed but the struggle. All our lives are consumed in possessing struggle but only when the struggle is cherished & directed to a final consummation outside of this life is it of any value. I want to be the best artist it is possible for me to be, under God.”

“Under God” is not O’Connor’s blithe echo of the pledge of allegiance to America. It is her confession of obedience to the God who both gives and demands all. It is also her discernment that God is present everywhere, whether hidden or manifest. As St. Thomas had taught her, God is pure act, the first and final cause of everything. Hence her own brain-tangling paradox concerning belief and unbelief: “No one can be an atheist who does not know all things. Only God is an atheist. The devil is the greatest believer & he has his reasons.”

This saying is worthy of Chesterton’s pronouncement on the “comforts” given to Job: “The riddles of God are more satisfying than the solutions of man.” The great conundrum, the perpetual source of unbelief, is evil in all its forms: natural, moral, metaphysical. The young O’Connor seeks no theodicy. “Evil is not a problem to be solved,” as she would later say, “but a mystery to be endured.”

Like God, therefore, the saints are paradoxical atheists. Seeing and knowing all things humanly as God sees and knows them divinely, yet also enduring to the end, they walk no longer by faith but by sight. And to know all is not so much to forgive all as it is to accept all, even the worst.

The demons, by contrast, “believe and tremble.” Satan takes his partial knowledge of things—perhaps like Ivan Karamazov’s rightful rage against the world’s unjust suffering—as if it were total knowledge. Made furious by such self-blinkered sight, the devil has only a shuddering belief in the God whom he refuses to worship. That a graduate student in her twenty-second year of life could fathom such mysteries reveals why, nearly a half-century after her death, Flannery O’Connor remains a writer with whom we must reckon.

Tucker and the Right

Something like a civil war is unfolding within the American conservative movement. It is not merely a…

Just Stop It

Earlier this summer, Egypt’s Ministry of Religious Endowments launched a new campaign. It is entitled “Correct Your…

What Does “Postliberalism” Mean?

Many regard “postliberalism” as a political program. In 1993, when the tide of globalized liberalism was at…