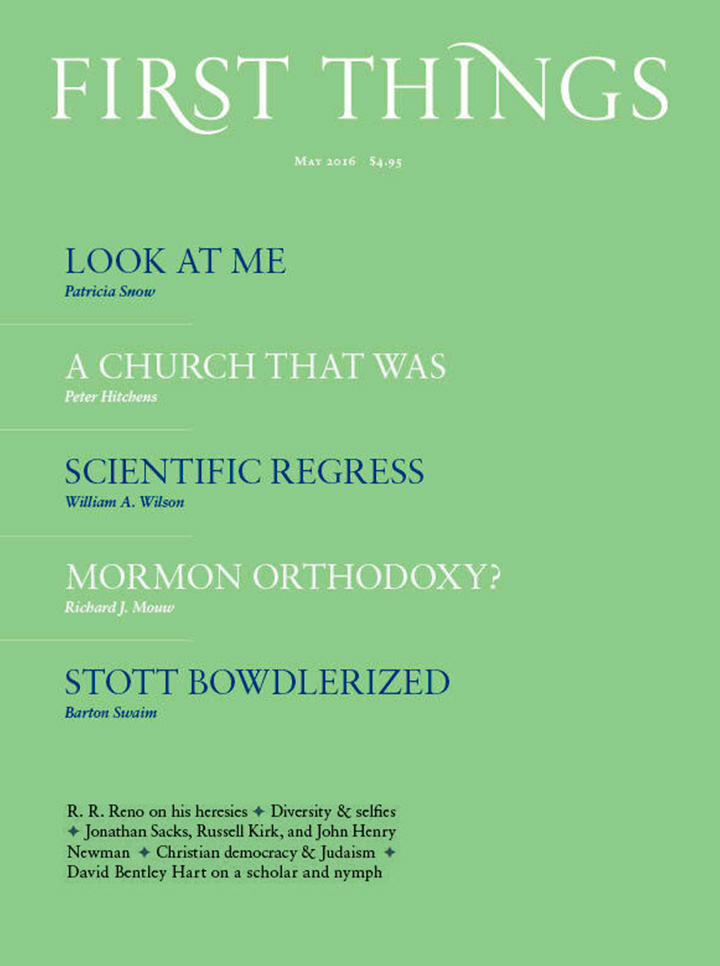

Russell Kirk: American Conservative

by bradley j. birzer

kentucky, 608 pages, $34.95

Drive up Route 131 from Grand Rapids, veer east of the Manistee National Forest, and you come to the village of Mecosta. This is a tiny hamlet of nineteenth-century settlement, much reduced from its ancient prosperity, yet the house is there, newly built from the ashes of its fiery ruin, Piety Hill, an Italianate pile, which began as a lumber baron’s residence, sank to a refuge for impoverished gentry, and became the seat of a literary man—a history suggestive of larger changes in American society since 1918. For in that year, Russell Amos Kirk, the heir and future occupant of the house, was born. And you may reflect with Kirk that the vanity of human wishes is writ large at Mecosta.

Or perhaps not. Kirk’s prose is elaborate, and maybe too easily satirized. But there was a serious point behind his literary affectations. In The Conservative Mind, he quoted John Adams’s claim that “grief drives men into habits of serious reflection.” Perhaps Kirk wrote so much—thousands of pages of books, articles, reviews, and letters—because his grief was so profound. As a lover of the old, the useless, and the beautiful, he had a lot to mourn.

The most surprising thing about Bradley Birzer’s new biography, then, is what a happy story it tells. Kirk’s life was not without challenges, but it seems to have been genuinely satisfying. Birzer describes The Conservative Mind as an exercise in “postmodern hagiography.” The term is more accurately applied to his own work. Russell Kirk: American Conservative is, in effect, a life of a saint.

A saint of what church? Birzer makes a case for Kirk’s orthodoxy, but acknowledges that his outlook was more Stoic than Christian, especially in his most intellectually productive period. The piety Kirk treasured was pietas in the Roman sense: reverence for the past, concern for the future, and respect for those who deserve it, regardless of the whims of fashion. That was the key to his distinctive brand of conservatism.

This attitude was novel when Kirk presented it to an unsuspecting public in 1953. Although the term “new conservatism” had been coined by Peter Viereck in 1940, it was not clear what its exponents hoped to conserve. Viereck aimed to uphold the New Deal. The young William F. Buckley, on the other hand, eschewed the term, preferring to describe his anti-statist views as “individualist.”

The publication of The Conservative Mind represented a decisive step toward resolving conservatism into a coherent position. Within its first few pages, Kirk gave conservatism a lineage going back to Burke, and six “canons” that distinguished it from liberalism, socialism, and other ideological alternatives. All of these claims have been challenged—especially Kirk’s reading of Burke. After The Conservative Mind, however, it was no longer possible to accept Lionel Trilling’s claim that “nowadays there are no conservative or reactionary ideas in general circulation.”

The book’s enthusiastic reception by popular and (to a lesser extent) academic readers took Kirk somewhat by surprise. Marginality and defeat were actually essential to his vision of conservatism. The book’s original title, in fact, was The Conservatives’ Rout. When he began the project in a fit of despondence after being dumped by his girlfriend, Kirk set out to write an elegy for history’s losers. What he produced was a manifesto for the most successful political movement of his time.

There have been many studies of the conservative movement, and Birzer wisely chooses not to rehearse them. Instead, he concentrates on Kirk’s distance from that movement, identifying two features of Kirk’s thought that placed him at odds with it from its inception.

The first of these dissonant notes was Kirk’s romantic Anglophilia. Following Burke, he did not simply argue that change should proceed slowly. He venerated the preindustrial order of landed estates and autonomous corporations. The problem was that this order was not just slipping into the past (as it was in Burke’s time). It was that nothing like it had ever existed in the country to which Kirk belonged and for whose citizens he wrote. For all his admiration for custom and continuity, Kirk articulated a social ideal that had little basis in American history. Notwithstanding this biography’s title, there was always something “un-American” about Kirk’s conservatism.

Kirk’s ambivalence about America’s liberal heritage made it difficult for him to translate his canons of conservatism into policy proposals. His follow-up to The Conservative Mind, A Program for Conservatives, was less favorably received because it revealed how little Kirk had to say about practical issues. In the early ’60s, Kirk wrote a few speeches for Barry Goldwater, who had praised The Conservative Mind as a personal inspiration. But the results do not seem to have been satisfactory to Goldwater’s managers, who excluded Kirk from the senator’s presidential campaign as it was first getting off the ground.

Kirk’s personal eccentricity probably didn’t help. A bohemian dandy, he liked bold suits, sported a sword-cane, and sometimes even affected a cape. Conservatism has succeeded politically in modern America only when it has been infused with populism. Kirk was unsuited for this demotic turn.

Yet the impracticality of Kirk’s conservatism was not based on any intellectual defect, as some of his critics charged. On the contrary, it was rooted in his understanding that politics is not the most important sphere of human activity. The ideologists of the burgeoning conservative movement included a disproportionate number of ex-Marxists who retained the conviction that ideas are weapons in the struggle for power. Kirk, on the other hand, learned from Irving Babbitt and Paul Elmer More to regard imagination as the essential human quality. For Kirk, defending freedom meant thinking, dreaming, musing—not winning elections.

Birzer is at his best discussing this side of Kirk. Although it is well known that Kirk enjoyed ghost stories, many readers will be surprised to learn that he was a bestselling writer of science fiction and horror, who sometimes earned more from his fiction than from his political books. Among his portraits of Kirk’s friendships, Birzer devotes considerable attention to Ray Bradbury. Like Kirk, Bradbury understood that imagination is not deception or idleness, and worried that this essential faculty was vulnerable to Americans’ characteristic insistence on practical results.

Birzer’s placement of Kirk in the company of literary men (and women, including Flannery O’Connor) helps explain why his influence waned in the ’70s and ’80s. Although he respected Ronald Reagan, Kirk was temperamentally at odds with the former Democrats who drifted toward his administration. Kirk’s conservatism was nostalgic and ultimately rather apolitical. He regarded neoconservatives, by contrast, as ideologues of capitalist democracy who were happy to overturn history and tradition if that helped them achieve their goals.

Because the targets of Kirk’s critique included many Jews—and because he used language reminiscent of classical anti-Semitism—this issue demands special attention. Birzer refutes accusations that Kirk was a bigot in any personal sense. In 1959, he even resigned from the journal Modern Age in order to distance himself from editor David Collier, whom he described as an “anti-Jewish freak.” Kirk’s Reagan-era criticisms of the United States’ alleged deference to Israeli interests have given him a reputation as a conservative anti-Zionist. Yet he defended Israel as an American ally in the ’50s and ’60s, when conservative attitudes were less uniformly positive toward the Jewish state.

Kirk was also an admirer of Leo Strauss, neoconservatives’ putative guru. In fact, he was inspired to found Modern Age by a negative review of Strauss’s work in Partisan Review. To be sure, Kirk had disagreements with Strauss, who believed traditionalism led to nihilism unless it was fused with the philosophical quest for permanent wisdom. But his battles were mostly fought with so-called “West Coast” Straussians, whose dogmatic interpretation of natural rights was very different from their namesake’s Socratic skepticism.

The real issue that separated Kirk from his neoconservative detractors was not religion or philosophy but war. Birzer shows that Kirk’s formative experience was his service as a chemical-weapons expert during World War II. Despite Kirk’s awe and delight in the Utah desert, where he was based, it was not a happy period. Kirk described the army as the “mailed fist” and professed to see little difference between the Nazis and his fellow GIs. Although he was relieved that America won the war, he was disgusted by victory celebrations made possible by atomic slaughter. “We are the barbarians within our own empire,” he told a friend.

It was Kirk’s refusal to see redemption in violence that made him suspect to enthusiasts for American hegemony. Without being a pacifist, he regarded war as a tragedy that corrupts the victor as well as inflicting terrible suffering on the defeated. In addition to recognizing its moral costs, Kirk understood that war tends to homogenize society and extend the authority of the state. For him, militaristic conservatism was a contradiction in terms.

These insights were unfashionable in the last decade of Kirk’s life. It was among Kirk’s disappointments to see the Wilsonian ambition to make the world safe for democracy become a bipartisan consensus under Presidents George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton. Birzer reports that Kirk proposed the former be “hanged on the White House lawn” for leading the United States into Iraq in 1991. One can only imagine what he would have said about George W. Bush—or Barack Obama.

Turning to Kirk for insight into today’s politics may seem like idle speculation. Actually, it is very much in Kirk’s style. In the first place, Kirk was a devotee of spiritualism who believed in conversation with the dead. And even if messages from beyond the grave are not real, the attempt to communicate with those who are not present can be a valuable act of moral imagination. If Kirk is right that society is a community of persons spanning past, present, and future, we have a responsibility to keep in touch with those who are dead as well as those who are not yet born—by imaginative, if not supernatural, means. By presenting this thorough portrait of an extraordinary man, Birzer allows us to commune with Kirk. That is an act of authentic piety.

Samuel Goldman is assistant professor of political science at George Washington University.