While it’s true that the song was not written by them, but by a minor folk singer Chet Powers, and that it had more chart success for another band, “Let’s Get Together” forever will belong to Jefferson Airplane. Their version was the best musically, and they made it an iconic part of their championship of and identification with Love.

Hey, people now,

smile on your brother.

Let me see you get together,

love one another right now.

Not only did they adopt this “Jefferson Airplane Loves You” slogan for signs and publicity copy, the liner notes to their first album said this:

All the material we do is about love. A love affair or loving people. Songs about love. Our songs all have something to say, they all have an identification with an age group and, I think, an identification with love affairs, past, beginning, or wanting . . . finding something in life . . . explaining who you are.

As I’ve previously discussed and will explain more in the next post, a key aspect of the 60s hippie counter-culture was this conflation of fraternal love (that exhibited by “loving people” who “smile on” and “get together” with their “brother”), with that of “love affairs,” and of course, with both of these with that of casual sex.

Jefferson Airplane’s full significance eludes us if we focus merely on their identification with acid and “acid rock,” and forget their key role as purveyors of Love. We might also note that musically speaking, they had a strong claim to be the culmination of the folk-rock sound, something you still hear on their justly-famous second LP Surrealistic Pillow, even if it usually gets categorized as “psychedelic” simply, and which you especially hear on their first, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, which contains not a hint of drug-advocacy.

In post-60s retrospect nearly everyone regards the original hippies’ emphasis upon drugs as extravagant and irresponsible, or at least naively overdone, but the passing of a rock-culture creed of “Peace, Love, and Understanding” has been far more openly regretted. That is an aspect of 60s counter-cultural faith that cannot die, despite its many apparent defeats. Nor should anyone, liberal or conservative, religious or atheist, entirely want it to—after all, as Peter shows us below, the key to understanding Pope Francis’s apparently sides-taking “political economy” remarks, is the correction they offer to complacent libertarian/libertine individualism.

So, what does that creed look like in one of its first 1960s flowerings? I.e., in this song? Most of the song’s creedal impact is in that famous chorus, but it also has three verses. They are not at the highest levels of song-lyric artistry, but they do their work, and are elusive enough in places to suggest depth. Here’s the first:

Love is but a song we sing,

fear a way we die.

You can make the mountains ring,

Hear the angels cry.

Tho’ the dove is on the wing,

you need not know why.

We begin then with a choice, that between the way of fear and the way of love. The final verse underlines this:

. . . You hold the key to love and fear,

all in your trembling hands.

One key unlocks them both, you know.

It’s at your command.

So the love of the chorus, which involves brotherly love, people in general “getting together” (“connecting,” E.M. Forester would say, or “resisting the heart-disease of individualism,” Alexis de Tocqueville would say), is posed against “fear,” which presumably is the motivation for conflict, war, and not regarding all of mankind and those around you as your brothers and sisters.

A Christian Praise Music reworking of the song would have to insist that the key is Jesus—that without His aid, we cannot practice such love (see Acts 4:31-35). But “Let’s Get Together” does contain one un-sunny aspect, and one admission that not all is at our command, as its central verse says this:

Some will come and some will go,

we shall surely pass.

When the wind that left us here,

returns for us at last.

We are but a moment’s sunlight,

fading on the grass.

Each of us will die. And that means for every happy hello, there will be goodbye. Death and the impermanency of personal life, including the impermanency of our loving connections with particular persons, are at the heart of the song.

The unfolding of the song thus suggests that awareness of this fact should be motivate us choose the way of love, over that of fear.

But why should it?

I suppose I need to turn to my Lucretius, to the athiest’s “consolation in philosophy” here in general. But that points, either along the lines of Buddhism to a general rejection of the world as illusion, which hardly inspires love even if it does a smiling acceptance, or along the lines of Socratism, to a pursuit of the best situation for practicing philosophy, which while it pursues friendship for the sake of such, hardly regards the many with no taste nor aptitude for philosophy as “brothers,” as persons deserving of one’s loving attention. Nor is it difficult to see how the likes of Locke and Franklin might use philosophic awareness of death to advise a prioritization of one’s own economic and legal-political-military security over the way of love, especially if you are uncertain about or no believer in God being love or commanding love. And from the counter-cultural view, it is but a step from such American establishment sobriety to the various soul-killing and war-causing ways of fear.

Well, there’s a lot more we could say here, and a number of other philosophers and poets, pagan, Augustinian, modern, and post-modern, that we might want to consider. We might particularly want to compare the message conveyed by the inspired poet who wrote Psalm 103, whose words—As for man, his days are as grass—are alluded to here.

But the song itself says nothing.

(Or does anyone else see how its basic argument is working?)

A song cannot be a treatise, but still. All it does say is this, at the beginning of the final verse:

If you hear the song I’m singing,

you will understand . . .

Well, sure, I catch the magic of the song, and before I begin thinking I want to believe in it, that is, that nearly all people (including those of nearly all kinds of religious belief or reasonable unbelief) can embrace the way of love.

My troublesome thinking is prodded in part by what First Things and McWilliams, Winthrop and Augustine, Paul and Luke, and yes, Jesus and the Old Testament, all teach about brotherly love.

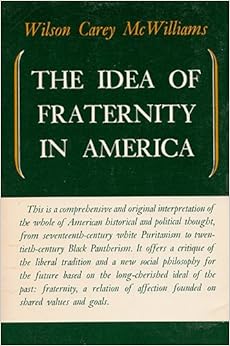

Wilson Carey McWilliams, who wrote the treatise on the idea of fraternity, defined it as a bond based on intense interpersonal affection, which also involves shared values and goals considered more important that “mere life.” Can all humans share such? All Americans?

And Psalm 103, regardless of whether Christians should interpret it as hinting at an afterlife, says awareness of our death should make us all the more grateful for God’s forgiving Mercy, but reminds us that this only comes upon them that fear him and to such as keep his covenant. Without that kind of fear, and the promise of that kind of covenant, what can the awareness of death do for us? It certainly seems incapable of inspiring all humans to embrace a fraternal way of love.

So, no, I don’t understand. I’m one of those who just don’t “get it” even though I hear the song’s spirit, cherish it, and want to surrender to it.

But one doesn’t need to read philosophers to know not to build a faith upon a feeling evoked in a song. Anyone who’s simply seen Oklahoma! recalls how the main songster Curley conjures a surrey with the fringe on top out of thin air that his beloved Laurey really comes to believe in, at least for the length of his song, and that he also tries to sing the loathsome Judd into committing suicide.

But such faith is just what this song requires. While the Christian teaching is that God is Love, it’s teaching is that Love is Song:

Love is but a song we sing . . .

That’s how the song begins, and in ultimate terms, where it ends also. According to it, acts of brotherly smiling love are a kind of act. Such acts draw others into a contagious multiplying passion to perform the same. So initiating this is a bet placed on the better side of human nature, and the reason for making this bet is that 1) we all must die, and 2) the song itself will make us understand.

Alas, it is but another typically American progressive, American pragmatic, and American heretical instance of recommending faith in the power of faith, linked here to art-as-religion by the song’s and the Airplane’s potent poetic impact.

By all means, choose the way of love. But you might have to Seek Ye First the Kingdom of God to understand why you should, and why you must continue to do so when life gets hard and un-San-Francisco-like. Seeking plenty of “love affairs” amid Jefferson Airplane freedom-on-modern-steroids rock music as a way to better “explain who you are” and to free yourself up for love in general is not, as we shall see in coming posts, going to put the discipline of loving all your brothers and sisters “at your command.”

Still, I must say I am more for “Let’s Get Together” and its symbolic representation of the most winsome aspect of the hippie creed, than I am against it. The hippies and children of hippies who really long for what Wilson Carey McWilliams longs for are my kind and my kin. I think we can talk together, and teach one another a thing or two. I smile upon them, and on my better days, not out of mockery.

A Happy and Loving New Year to All!

The Battle of Minneapolis

The Battle of Minneapolis is the latest flashpoint in our ongoing regime-level political conflict. It pits not…

Of Roots and Adventures

I have lived in Ohio, Michigan, Georgia (twice), Pennsylvania, Alabama (also twice), England, and Idaho. I left…

Our Most Popular Articles of 2025

It’s been a big year for First Things. Our website was completely redesigned, and stories like the…