Henri Pirenne, in his Economic and Social History of medieval Europe, describes the regulation of economic life in medieval towns during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Pirenne is admittedly old news, and perhaps more recent studies have corrected some of his claims.

The town government had two main aims: “publicity of transactions and the suppression of middlemen.” Later, Pirenne adds that economic regulations in the towns were “governed by the spirit of control and by the principle of direct exchange to the profit of the consumer.”

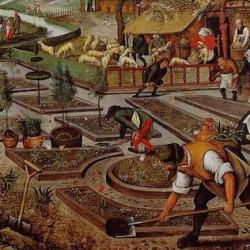

Protecting the consumer took the form of an array of “meticulous regulations.” Butchers, for instance “were forbidden to keep meat in their cellars and bakers to procure more grain than was necessary for their own oven; no burgess was to buy more than he needed for himself and his family. The most minute precautions were taken to prevent artificial increases in the price of food. Often a maximum was fixed; the weight of bread was proportioned to the value of grain; the maintenance of order in the markets was entrusted to communal officials whose numbers were continually increasing . . . . All commodities were carefully inspected and those which were not irreproachable in quality or, in the happy expression used in the documents, ‘loyal,’ were confiscated or destroyed, in addition to penalties which often extended to banishment.”

In short, “the liberty of the individual was ruthlessly curtailed, and the sale of foodstuffs subjected to a regulation almost as despotic and inquisitorial as that which applied . . . to small-scale industry.” Again, “the regulative character which had dominated the whole economic legislation of the Roman Empire did not disappear with the fall of the latter. It is still clearly recognizable, even in the agricultural period of the Middle Ages, in the control exercised by kings or the feudal powers over weights and measures, coinage, tolls and markets.” In cathedral towns “the bishops were . . . concerned with establishing the principles of Catholic morality, which imposed on sellers a justum pretium which they might not exceed without incurring the penalty of sin.”

With regard to industry, the guild system arose not only from the free association of artisans, but also from the pressure of town government: “the public authorities regulated town industry by dividing artisans into as many groups as there were distinct crafts to supervise . . . . It would be a complete mistake to envisage the right of self-government as inherent in the nature of gilds. In a large number of towns they never shook off the tutelage of the municipal authority and remained mere organisms functioning under its control.” The guilds of Nuremberg, he says, “never ceased to be strictly subject to the Rath (Municipal Council), which even refused them the right to meet without its authorization and went so far as to oblige them to submit their correspondence with the artisans of foreign towns to it.”

Towns exercised quality control of their industries: “The rigid regulation of the towns made scamped workmanship as impossible, or at least, as difficult and dangerous, in industry as was adulteration in food. The severity of the punishments inflicted for fraud or even for mere carelessness is astonishing. The artisan was not only subject to the constant control of municipal overseers, who had the right to enter his workshop by day or night, but also to that of the public, under whose eyes he was ordered to work at his window.”