The biblical writers don’t know how to end a story.

Genesis 22, one of the best-known and most dramatic of biblical texts, the story of Abraham’s interrupted sacrifice of Isaac, is a case in point. Give the episode to a Hollywood script writer and the thing would end with a tearful reunion between Isaac and Sarah, the entire household of Abraham looking on beaming and applauding, followed by a quiet denouement, a scene of Abraham contemplatively watching the sun set or looking up at the starry night sky. That’s the way to end a story.

Genesis 22 instead ends with a genealogy , and it’s not even Abraham’s. Abraham hears that Milcah has borne eight children to Abraham’s brother Nahor (22:20-22). The story of Isaac’ near-death and resurrection ends with a list of his cousins.

Of course, the author knew what he was about and there are several reasons to end the story of Isaac that way. For starters, though, this ending shows that the writer does not write for emotional effect. As Erich Auerbach ( Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature ) pointed out years ago, all of the emotional drama of the story is back-grounded. This is a classic example of what Alter calls the “reticence” of biblical narrative ( The Art of Biblical Narrative

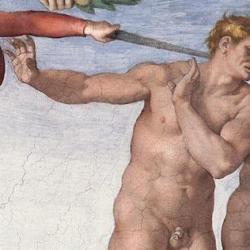

). No Kierkegaardian flourishes. No tears or anguish. A straightforward story of God’s command, a father giving up his only son, human sacrifice, near-death, angelic intervention, miraculous provision and restoration. Ho-hum. All in a day’s work for the father of us all. Think of the courage it took to tell this story this way. There’s no writer alive who would have the guts to pass on the pathos. Call it the courage of the Spirit, but it’s still courage.

But the biblical writers are very interested in the meaning of these events, and they communicate this meaning with an understated beauty. The genealogical coda to the story of the Adeqah is perfect, for two reasons. First, it confirms that God’s promises to Abraham are reliable. Yahweh promises Abraham an abundant seed that will bless the nations, and reiterates that promise after Abraham proves by his obedience that he fears God (22:12, 15-18). That promise is not long is being fulfilled. Immediately after Abraham obeys, Yahweh brings news of fruitfulness. Isaac’s “death” is followed by abundant life, not to the circumcised house of Abraham but to their uncircumcised cousins. The nations begin to be blessed with an eightfold seed, as soon as Abraham obeys in faith. And of course, the nations begin to multiply and fill the earth in the aftermath of the death and resurrection of the One Greater than Isaac.

Second, the genealogy of Nahor comes to a climax not with his eight sons, but with his granddaughter, Rebekah, fathered by Nahor’s son Bethuel. Rebekah of course becomes Isaac’s wife, and this is her first introduction. Isaac bears the wood of the sacrifice and comes under the knife, and immediately the bride steps on the stage. Isaac is another Adam, “cut” and sacrificed so that God can build a new Eve. James Jordan has pointed out that every covenant has an initial masculine phase and a climactic feminine stage – Adam, then Adam and Eve; the tabernacle instructions given, then given again emphasizing the women’s contributions; a census of fighting men in Numbers, and then a second census including women; Jesus, then Jesus and His Bride. The bridal phase comes through death and resurrection. Isaac is another example of the pattern, as he goes to the altar and then rises to receive a bride. Significantly, the death of his mother intervenes in chapter 23; the mother dies as the bride steps into the story, an old Israel giving way to a new.

Whatever we might think, the writer of Genesis knew what he was about.