Too much of the discussion of nature and the supernatural is conducted in the idiom of Aristotle rather than the Bible. Most obviously, for Scheeben, Rahner, and even de Lubac (though to a lesser extent), the issue is framed as a question concerning the constitution of human “nature” or the make-up of the “creature,” whereas the Bible reveals a particular being in particular circumstances, who is given the proper-generic name Adam.

It is more fruitful to work out human nature and destiny from a consideration of Adam’s concrete condition (what Rahner calls his “concrete quiddity”) in the garden, rather than in the abstracted and general terminology of metaphysics. What happens when we do that?

I can give only a brief sketch, but a few points stand out. Rahner (Foundations of Christian Faith, 123), says that man was created “empty” but with the promise of filling. This is perhaps no more than a dramatic way of stating that humanity was created for a destiny that surpassed its original state, but if it suggests an actual emptiness, then it goes quite against the account of Genesis 2. When we look at Genesis, we find, first, that Adam was created in communion with God.

This is true not only in the sense (implied by the very notion of creation) that His existence depended on some kind of original participation in God (“living, moving, and having his being”), but also in the specific sense that he was created in a living relationship of communion and communication with God. Adam was placed in the garden, God’s sanctuary, with free access to the tree of life. Yahweh his Creator spoke to Him, giving him a command, a threat, and an implicit promise. In Genesis 3, after Adam and Eve sin, Yahweh comes walking in the “Spirit of the day,” as if coming to meet with the man and the woman were the most natural thing in the world. To put it another way, Adam was not created merely as a “servant” who was destined to become a friend, as von Balthasar and Scheeben put it. He was created a son (Luke

At the same time, there is clearly an “incompletion” in the garden. Adam had free access to the tree of life, but not to the tree of knowledge of good and evil. The tree of knowledge was not, however, permanently off-limits to Adam, but was implicitly promised at a later time. Once he was prepared, he would have been permitted to eat the tree. The second tree signifies and communicates a new state for Adam, a state in advance of his original condition but a state he was designed to reach.

This is the hint in Genesis 2 that Paul describes in terms of a contrast between “soulish” (not “natural” – the Greek is psychichon rather than phusikon) and “spiritual” (pneumatikon) existence. Paul states that the very existence of a “soulish” humanity was a pledge of a “spiritual” humanity: If there is a soulish body, there is also a spiritual (1 Corinthians

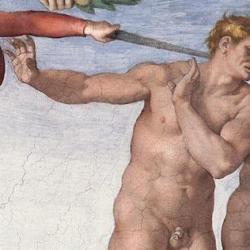

The path toward this Spiritual existence was not a path of smooth ascent, an uninterrupted progression. Genesis 2 records a movement from original glory to greater glory in the creation of the woman, who is the glory of the man (1 Corinthians 11). To make the transition from glory to glory, Adam was put into deep sleep, a near-death state, torn in two, repaired and reawakened. It was through this death-like experience that Adam reached his greater stage of glory, the glory of communion with a bride who was one flesh with him. He progresses from existence as an “I” to existence as a “we” through a sacrifice procedure of dismemberment and restoration.

That was to be the progression to the tree of knowledge as well. “In the day that you eat of it, you shall surely die,” was not only a threat to keep Adam from seizing the fruit for himself. It was also a promise: In the day he ate from the tree of knowledge, he would die to his soulish existence and enter into a spiritual existence (for more on this, see James Jordan’s essay in The Federal Vision).

This brief sketch captures what I want to say about human nature as created, and the destiny of humanity. It is a radically non-extrinsicist account, first because it affirms Adam’s original communion more emphatically than even the theologians of the nouvelle theologie and, second, because it treats Adam’s advance in glory as part of the proper story-line of human history. It is also superior to most forms of the nature/grace scheme because it does not even hint that the original state of Adam or creation was anything less than good, does not involve any assaults on material reality, does not assume, against Scripture, that Adam was created as “servant” and not son.

At the same time, this account also protects against the dangers that de Lubac and Rahner feared from a thorough-going intrinsicism, a collapse of grace into nature. Does this account protect the gratuity of the original creation, and make created participation in God foundational? Yes; that is one of the foundational claims of my whole story. Does this account protect the progressiveness of human destiny, the fact that man’s finality exceeds and transcends his original condition? Yes; Adam was created a priestly servant destined to be king, created in fellowship with Yahweh but destined for ever and eternally deeper fellowship, created as crown prince but destined to ascend to the throne. Does this account protect the eruptive character of this grace? Yes; Adam would not simply grab the fruit of the tree of knowledge one day, but would die and rise to it in the day he ate. (This account is also consistent with the Scotist and Orthodox notion that the incarnation was necessary even apart from sin.) It is through that disruptive event that Adam would reach his final telos, and be united to God more fully than ever.

The great question for this account, though, is whether it protects the gratuity of grace. Is Adam’s admission to the tree of knowledge a surprising and unexpected gift? Here is where my criticisms of the entire nature/supernatural paradigm come into play. As I see it, the problem of gratuity arises from the questionable nature/supe

rnatural framework, so that dispensing with the framework dispenses with the problem. The framework requires, as Rahner realizes, that the gratuity of grace be different in kind from the gratuity of creation. Leaving sin to the side (since we are not discussing the question of God’s favor to sinners, but of God’s favor to creatures), this does not seem at all necessary. Adam received his existence as an unexacted gift from a loving Creator. Each breath and heartbeat and mouthful of food was a further unexacted gift from this loving Creator, as was each seventh-day meeting with Yahweh in the garden.

At some point, Adam would have received an even greater gift, the gift of access to the tree of knowledge, of deification, of union with God, through an experience of death and resurrection. The gift is richer, but its richness consists in the nature of the gift itself and not in the “quantity” or “quality” of its graciousness. The gratuity of this further gift is the same unexacted gratuity expressed in the original act of creation. It is a greater gift, but neither more nor less gratuitous.

I believe that an account of human nature and destiny along the lines I suggest is more fruitful than the traditional or new accounts have been. I have the lingering sense that at a number of points I have simply changed the terminology, that I have not said anything substantively different from Rahner or de Lubac. If that turns out to be the case, I will be the last one to object. Protestant though I am, I could not protest if I found myself in happy agreement with such profound and pious Catholic thinkers.