In recent years, historians have argued that the state didn’t exist in the medieval period. States are born of war, argues Charles Tilly, especially the wars of the early modern era. Annales scholars and their descendants saw tiny medieval duchies and counties as antitheses to centralized state power.

Sverre Bagge is skeptical of this new orthodoxy, and in Cross & Scepter, his lucid recent study of the rise of Scandinavian kingdoms, he examines the medieval contribution to the rise of the modern state.

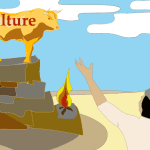

In Bagge’s account, the church plays a central role: Symbols such as “legitimate birth, specific qualifications, or formal elections . . . assumed particular importance with the introduction of Christianity and the formation of the kingdoms.” Scandinavia’s kingdom took rise from the combined efforts of cross and scepter, and the cross came first: “Bishops and archbishops were elected and consecrated and wore miters, staffs, rings, and crosses as signs of their dignity. Kings eventually followed a similar path, the office being filled according to formal rules and by an incumbent who wore a crown and scepter.” Cross and scepter replaced the fist that had governed Scandinavian politics earlier (2).

Behind the church’s efforts was a particular vision of politics, according to which it was God’s will for the world “to consist of a number of separate territories, each governed by a king” who would “respect each other’s rights and not interfere in the realm of their neighbors” (6). This was, Bagge notes, a radical departure from the earlier Roman system, whose dissolution “forced the church to adapt to political division,” thus laying the groundwork for the nation-state, “one of the most distinctive features of Europe compared to other civilizations” (6).