Rosalind Williams Notes on the Underground is an examination of 19th-century narratives about underground worlds, which she sees as prophetic texts: “Subterranean surroundings, whether real or imaginary, furnish a model of an artificial environment from which nature has been effectively banished. Human beings who live underground must use mechanical devices to provide the necessities of life: food, light, even air. Nature provides only space. The underworld setting therefore takes to an extreme the displacement of the natural environment by a technological one. It hypothesizes human life in a manufactured world. What would human personality and society look like then?” (4).

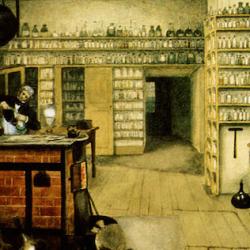

Williams’s insight is based on Lewis Mumford’s Technics and Civilization, where Mumford not only describes the effect of mining on technological development but takes mining as a metaphor for working environments in a technical age. Mumford wrote, “The mine . . . is the first completely inorganic environment to be created and lived in by man: far more inorganic than the giant city that Spengler has used as a symbol of the last stages of mechanical desiccation. Field and forest and stream and ocean aue the environment of life: the mine is the environment alone of ores, minerals, metals. . . . Except for the crystalline formations, the face of the mine is shapeless: no friendly trees and beasts and clouds greet the eye. . . . If the miner sees shapes on the walls of his cavern, as the candle pickers, they are only the monstrous distortions of his pick or his arm: shapes of fear. Day has been abolished and the vhythm of nature broken: continuous day-and-night production first came into existence here. The miner must work by artiJicia1 light even though the sun be shining outside; still further down in the seams, he must work by artijicial ventilation, too: a triumph of the ‘manufactured environment’” (quoted, p. 5).

Tales of adventures exploring underground worlds go back several centuries, but Williams argues that something new emerged in the nineteenth century: “Instead of being a place to visit, the underworld becomes a place to live. Instead of being discovered through chance, an underworld is constructed (or a natural underworld is vastly enlarged) through deliberate choice” (10). This new sort of fiction was a response to the advance of science and technology: Science had made the discovery of an underground world unlikely; technology had made the creation of such a world completely credible.

New forms of narrative went along with new patterns of aesthetic sensibility: “New aesthetic concepts-first sublimity and later fantasy-were invented that expressed the emotional power of subterranean environments, a power not encompassed by the traditional aesthetic terminology of beauty and ugliness. Furthermore, sublime and fantastic images were extended from subterranean environments to technology in general” (17). Williams discerned, however, a difference between American and European conceptions, which she summarizes in terms of a contrast between British and French “verticality” with America’s “horizontal” imagination.

Digging down took on a class dimension, since the lower classes are imagined as being beneath the surface, metaphorically “pieces of buried evidence to be dug up and analyzed.” But the narratives, Williams argues, reveal less about the lower classes and more about “middle-class anxieties” (21).