In a brilliant brief discussion of the Reformation revision of Christian sacramental theology, Philippe Buc (Dangers of Ritual) writes:

“The Reformation’s success in sixteenth-century Europe can be explained partly by the skill with which its propagandists mustered against the Roman Church notions basic to the medieval definition of Christendom. They positioned themselves on the side of the spiritual against a putative carnal, and attributed to the enemy a mindless ritualism, recycling for their polemical descriptions of Catholic rites late antique depictions of pagan cults, but perhaps more pointedly the opposition between the New Law and the Old Law.”

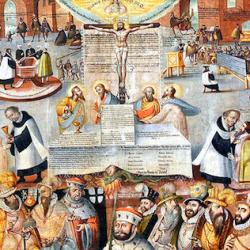

In short, the charge of “Judaizing” was a central plank in the Reformation agenda: “Catholic rites were all ‘ceremonies,’ just as Jewish rites had all been ‘ceremonies.’ Unlike the few sacraments now acceptable to the Reformers, they were at best dispensable dross, at worst a cause of perdition. . . . Since the relationship between regnum and sacerdotium could be conceived in terms of the contrast between the Old Law and the New Law,” the distinction between ceremonies and sacraments could also be correlated to the hierarchized complementarity of Polity and Church” (164).

Thus the Reformers reclassified a number of ceremonies that had once been considered sacraments (marriage) or sacramentals (coronation) as external political rituals, helpful for maintaining order and cohesion within a polity, but not conducive to spiritual unity. The result was a new configuration of church and world. As Buc puts it, “four sets of dyads were put in correspondence: (1) polity-Church; (2) Old Testament-New Testament; (3) ceremonies-Spirit; (4) order-salvation” (166). That may be too schematized, but it’s accurate enough to make one uncomfortable.

The division of external political rites and spiritual sacraments also affected sacramental theology. Melanchthon (unfairly) attacked Zwingli for teaching “that the Lord’s Supper was instituted for two reasons. First, that it be a mark (nota) and testimony of our profession [of Faith], just as a specific shape of cowl is a sign of a specific [monastic] profession. Then they believe that it pleased Christ [to institute] this mark, that is a banquet, mostly to signify a mutual conjunction and friendship between Christians, because symposia are signs of pact and friendship. But this is a civil [menschlich] opinion; it does not make manifest the main usage of things that God transmitted to us, [but] speaks only about the exercise of charity, which profane and civil human beings understand in some manner, [and] does not speak of the Faith, which few human beings understand as what it is” (quoted Buc, 167).

If this is all sacraments are, then “the church will differ in no way from a mere politia externa.” It will be functionally Jewish (167-8, Buc’s wording).

Even if this were fair to Zwingli, even if Zwingli were as reductionist as Melanchthon makes him out to be, his criticisms would be wrong-headed. He assumes, rather than argues for, a dichotomy of Faith and Love, and between civil and spiritual. What if sacraments were signs of spiritual goods just because they were signs of the “civil” union of human beings with one another (at God’s table, no less!). Why is that not “spiritual” or “Faith” enough for Melanchthon? Why isn’t it enough to say that the sacrament signifies salvation just by gathering human beings to eat and rejoice together in the presence of God?