Neoteny comes from two Greek words, “new” and “hold.” As Robert Pogue Harrison defines it (Juvenescence, 18), evolutionary biology speaks of neoteny as the “persistence of fetal, larval, or juvenile features in adult organisms.” Harrison means something more broader, “a modified type of development that brings juvenile traits to new levels of maturity, where they are preserved in their youthful form” (21).

Einstein enjoyed the benefits of neoteny: “Toward the end of his life Einstein claimed that his breakthroughs in physics were due to the fact that, in mind and in spirit, he had remained a child his entire life. Now Einstein’s mind obviously did not cease its development when he was still a child. What he meant was that he never stopped asking more probing and technically sophisticated versions of those basic questions that parents never quite know how to answer: Why is the sky blue? How old is God? What can’t I see the wind? It takes a childish sort of inquisitiveness to wonder what an atom is made of, or under what conditions time might move backward, or what light would look like to someone traveling at its speed on a parallel beam. Einstein’s mind continued to grow in capacity and complexity while holding on to its intrinsic wonder, curiosity, and love of the marvelous.”

For Harrison, this “is another way of saying that he was quite a genius” (21), since “our genius derives from our reluctance to grow up” even while wisdom comes from “our heightened awareness of death” (22).

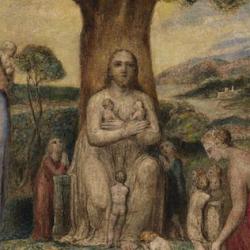

Harrison’s book examines some of the major “neotenic” revolutions in cultural history. Christianity is one: “one could speak of early Christianity as a neotenic revolution” (81). God comes on the scene as a little child, and Jesus calls His followed to become as little children, “to embrace the humbleness of Jesus himself, who was born in a manger and died on a cross” (83). Become as a child is a “transvaluation of values,” that turns “the lowest into the highest, the highest into the lowest, such that wise men now come to pay homage to the child.” What Nietzsche called a transvaluation of values Christianity calls a “conversion” – “literally a turning around, or upside down” (83).

This becomes quite central in Paul, though the figure of the child is embedded in Paul’s discourse on faith. Faith is “unconditional trust – the sort of trust, precisely, that a child puts in its parents.” It’s not “the innocent, instinctive, blind trust of naive, unreflecting children” but rather “an existential commitment taken with full awareness of what is at stake in the decision to put one’s trust resolutely in God through Christ.” Becoming childlike is not reversion but a retrieval in an adult believer of “the child’s innate capacity for trust.” This is another way to talk about conversation, the conversion of “the child’s trusting disposition into an adult mode.” Retaining childlike trust in adult life is “the essence of Christian neoteny” (87).

Typology is rooted in a similar instinct. In response to the pagan criticism that Christianity was new, Christians said that Moses is older than Homer, and that they are the heirs of the ancient tradition of the Jews. This was the only way for Christianity “to remain a child. It had to become an old man. It did this by reinheriting and transforming the wisdom of its predecessors and incorporating that wisdom into its genius, in such a way as to secure a rock-solid institutional foundation for the childish trust and foolishness that to this day remain the primary means of access to the inner core of the Christian kerygma” (92).