With Their Rock Is Not Like Our Rock, Daniel Strange has written a superb book on the theology of religions. The book is careful, patient, methodologically conscious and conscientious, combining biblical and systematic theology with missiological interest. Strange makes extensive use of the Dutch Reformed tradition of Herman and J.H. Bavinck, Cornelius Van Til, John Frame, and Vern Poythress, but his research is broad and thorough.

Strange states his thesis several times: “From the presupposition of an epistemologically authoritative biblical revelation, non-Christian religions are sovereignly directed, variegated and dynamic, collective human idolatrous responses to divine revelation behind which stand deceiving demonic forces. Being antithetically against yet parasitically dependent upon the truth of the Christian worldview, non-Christian religions are ‘subversively fulfilled’ in the gospel of Jesus Christ” (42).

That’s a mouthful, and fortunately most of Strange’s sentences are not so dense. To unravel this a bit.

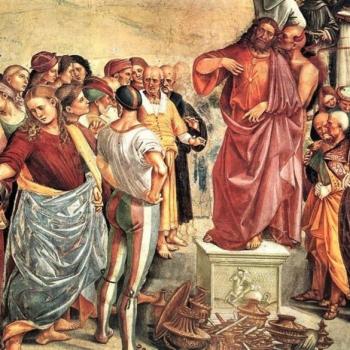

First, the biblical revelation part. Strange devotes a chapter to the biblical portrayal of man as homo adorans, created for worship and even after the fall inescapably bound in relation to a personal Lord. As image, human beings have an impulse to worship; because of sin, the human impulse to worship is distorted. Sinners want to flee from God at the same time they cannot escape His presence and revelation, and what Strange does not hesitate to call “false” religions arise from this tangle.

But, second, taking biblical revelation as authoritative also means that Strange takes the early parts of the Bible as an historical account of the early history of man, as a religio-genesis. False religions are not merely responses to natural or general revelation; they are not merely expressions of the created impulse to worship. “Remnantal revelation” is also a factor, the memory and tradition, distorted by sin and through time, of special revelation. Strange analyzes the account of Babel as an account of the diversification not only of ethnicities and languages but also, inseparably, of religions (he neatly connects Genesis 11 with Moses’s claim that God apportioning the heavenly host to the nations [Deuteronomy 4:19], 133-149). “Influential” revelation is another factor, the impact that ancient Israel had on surrounding nations. False religions are thus the product of a complex interaction of various factors. In every respect, false religions are parasitic on the true.

Behind these human factors, third, are demonic deceptions. In his treatment of the fall, Strange notes that the “false religion” adopted by Adam and Eve is the product of Satanic temptation. Demonic influence stands at the root of idolatry. Strange is well aware of evangelicals who argue that there were moments of benign pluralism in biblical history, and he convincingly disposes of the arguments. Idolatry is antithetical to the faith of Israel and the church, and it is seen as such throughout the Bible.

At the same time, as his thesis indicates, he recognizes that Christianity answers to the distorted elements in other religions. And so the gospel fulfills the deepest dreams of paganism, while at the same time fundamentally subverting the same paganism. As Cornelius van Til put it, “Christianity stands . . . in antithetical relation to the religions of the world, but it also offers itself as the fulfillment of that of which the nations have unwittingly had some faint desire” (quoted, 268).

This issue is immensely important, and likely to increase in importance—not only in missiology but as it becomes a contested issue among Christians. As Strange says, Evangelicals have been slow to develop a considered response. His book is an excellent contribution to the effort to catch up.