The Incarnation of God by John Clark and Marcus Peter Johnson is an excellent book. This accessible book offers a mini-systematics from the perspective of the incarnation, showing how the incarnation affects our understanding of God and His attributes, atonement and salvation, church and sacraments. They end with a chapter examining the import of the incarnation for sexual ethics. The theology they present is systematically coherent, moving from Trinity to incarnation to salvation as incorporation into the Son and the Triune fellowship. Union with Christ takes center stage in their soteriology.

Throughout, the authors’ theological judgments are generally well-informed and sound. They argue, for instance, that the attributes of God have to be understood as attributes of the God who is Father, Son, and Spirit – that is, as attributes of a triune communion. Holiness, they insist, is not, as many think, “the antithesis of relationship” but a “relational reality”: God is the “Holy One of Israel in their midst” (89). Divine simplicity, they write, “is rightly understood only when informed and normed by his triunity. God’s simplicity affirms his unity, but in no sense does this affirmation imply a unitarian notion of God” (77). They reject impassibility (97), though here it’s not clear that what they reject actually is the classic notion of impassibility. They argue (rightly) that the Son is incarnate into flesh, into our dilapidated condition, and not into some hypothetical pristine human nature.

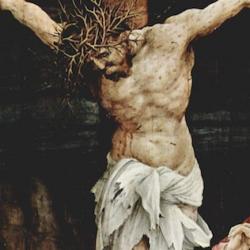

Just as importantly, they express the mystery of the incarnation with the kind of ecstatic prose that it deserves.

For instance, in a chapter explaining how the incarnation makes God known (in which Clark and Johnson sharply, rightly, charge that many operate by an “epistemological Pelagianism”), they make this point: “God does not merely tells us about his love for his Son, nor does Jesus merely tell us about the love his Father has for him. Such knowledge would perhaps be interesting, even novel – but it would not require the enfleshing of God’s Son, and it would not be saving, eternal-life-giving knowledge. The stunning reality of the incarnation is that the love that God the Father has for God the Son has come into our humanity through the enfleshing of the Father’s Son. The love of God for his Son has actually entered into our humanity, allowing our humanity entrance into that love” (57-8).

Or this: To say that God is love is to say “that God is himself the love by which he loves. Just as there was never a time when God was not Father to his Son, so there was never a time when God was not love. Love is not a disposition in God that comes to expression only in the creation and redemption of the world; rather, God simply is and always has been the love by which he loves the world” (67).

They recognize that the incarnation extends the Son’s “relationship with his Father into our human existence, through the Spirit. . . . the pericoretic relation of Father, Son, and Spirit . . . has taken up residence in our human flesh in the person of Jesus Christ. Thus, the love and life that God is and always has been as Father, Son, and Spirit comes to us as the Spirit joins us to the Son that we might know his Father” (69).

In Jesus, “we are granted to know the very being of God.” This is condescension, but they rightly note that “the incarnation neither contradicts nor obscures who God is, as if God were known more fully and clearly prior to or apart from the appearing of Immanuel. God the Son come in the flesh is not an instance of divine retreat, the regressive revelation of God! On the contrary, in this stunning act of divine invasion, of progressive revelation, God accommodates himself to us in the humanity of Jesus Christ to reveal himself all the more radiantly” (80).