Lisa Deam’s A World Transformed is an engaging, meditative study of what she calls the “spirituality of medieval maps.”

Maps, she argues, are never neutral. They “show what their users want and need to believe about the world. They allow us to daydream, to plot and scheme, to envision our future. They help us take journeys, both real and imagined. Maps are belief systems in miniature” (19).

Modern maps elide worldview. Not medieval maps, which, whatever the makers thought about the real configuration of the terrain, depict a vision of the world, typically a Christian one. Maps were made in a T-O format – circular overall, but with a T formed by the intersection of Asia, Europe, and Africa. Jerusalem is at the center of the T on many maps, sometimes with the risen Christ in the center of Jerusalem. At the margins are monsters, the evil that stalks the edges of human life. In the fourteenth-century Hereford map that Deam explores most fully, there’s a picture of St Augustine in north Africa.

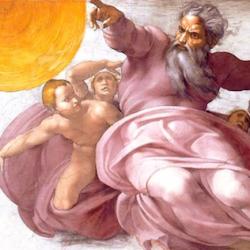

The Ebstorf Map (c. 1300) combines the “forbidden garden at the top of the world” with “monsters at the edges of the earth” – twenty-four monsters along the Southern tip of the map. Yet the map is also encompassed by Jesus: “the head, hands, and feet of Jesus peep out from behind the round image of the world. It is as though Jesus stands behind the earth, grasping it firmly in his hands. . . . He even holds the monstrous creatures; his left hand appears inside the boxed area that pictures a Troglogyte. . . . An adjacent inscription reads, ‘He holds the earth in his hands’” (52).

This is a world in which believers feel quite at home.