Andrew Walls (The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History) argues that Europe’s encounter with non-Western peoples was one of the key factors in the secularization of Western politics.

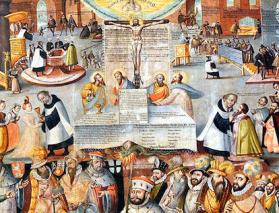

At a moment when Europe’s hegemony over the world seemed secure, it came “by means of the expansion of the Iberian powers, into massive contact with the nonWestern world. With Christianity essentially territorial in concept, all recent experience pointed to crusade as the natural mode of relationship.”

And so conquistadors embarked on their crusades, but destroying the idols of the Indians was only half the battle: “trying to comprehend a society so different from the norm of Christendom exposed the gaps in European intellectual, and indeed theological, equipment.” For pastoral reasons, the missionaries had to make use of the conceptual and linguistic equipment they found among the peoples of the new world: “how could an Andean peasant make a confession to salvation without understanding? The only way forward was to grapple with understanding the Andean vernaculars and attempt to explain Christian doctrine in indigenous terms.” While the official policy was to use loan-words from Latin or Spanish, but that wasn’t a workable solution: “if confession is to be made from the heart, loan-words have to be understood in the vernacular.”

The Portuguese experience was especially important. Portugal controlled vast imperial territories, but “did not have the power of coercion, whose function was to commend, persuade, demonstrate and discuss; and who in order to perform these tasks needed to understand and enter into the life of other societies.” Portugal’s army was too small, her resources too meager, to “compel them to come in.” They had to re-learn arts of persuasion.

More directly, the new world situation demanded new configurations of the relationship between the Catholic church and European Catholic powers: “Padroado or Patonato by which the Pope not only gave to the monarchs of Portugal and Spain monopoly powers of rule and trade in the new worlds which they were now meeting, but committed to them the oversight of the church in those lands. The latter provision marks thefirstreflex action of colonialism upon Christendom, and perhaps marks the first step in its secularization.”

It was in the later missionary movement of the nineteenth that the gap between the aims of empires and the aims of the missionaries became stark. Missionaries watched in horror as the British Empire used its power to advance the cause of Islam throughout Africa: “At the beginning of that century the great Islamic power had been the Sultan of Turkey; by the end it was the British Empire, with the Royal Republic of the Netherlands in second place. The missionary interest was lamenting that Britain kept missionaries out of the emirates of Northern Nigeria, that Britain was encouraging the Islamization of the Sudan. Furthermore, the British did these things more efficiently than the Sultan ever did. In the twentieth century it appeared that the most considerable religious effects of imperial rule were the renovation and reformulation of a Hinduism that had seemed to be disintegrating at the time British rule was established, and a quite unprecedented spread of Islam.” Walls concludes with this shocking claim: “Colonial rule did more for Islam in Africa than all the jihads together.”

And he concludes generally: “Colonialism, in fact, helped to transform the Christian position in the world by forcing a distinction between Christianity and Christendom.”