It was not uncommon in the early 19th century for blacks and whites to worship together. As Niebuhr observes, they “did not enjoy complete fellowship” and there was certainly not equality between them, yet “they participated in the same services and were members of the same denominations. . . . Domestic servants, if not plantation slaves, often shared with their masters and mistresses the ministrations of the same pastors and communed at the same Lord’s table. The Anglican Church was the leading denomination among the Southern masters and this church was officially very mindful of its duty toward the slaves, however inadequately its members may have practiced the ideals set forth by its slaves” (Social Sources of Denominationalism, 240).

Niebuhr quotes Georgia Bishop Stephen Elliott’s comment that common participation in church services “would tend very much to strengthen the relations of masters and slaves . . . bringing into action the highest and holiest feelings of our common natures. There should be much less danger of inhumanity on the one side, and of insubordination on the other, between parties who knelt upon the Lord’s Day around the same table, and were partakers of the same communion” (242).

That quotations suggests something of the mix of motives that produced the mix of races, and Niebuhr is careful to dispel any idyllic portrait of racial harmony: “The white man’s fear of Negro independence was as important a factor in the matter as the white man’s concern for the Negro’s soul.” Lest blacks get the wrong idea, theologians and churches made it clear that the freedom that the gospel promised was a spiritual rather than a social freedom (248-9). Yet there were large numbers of black members in Methodist and Baptist denominations, and majority white churches with black pastors. When First Baptist of Richmond had a revival in 1831, 217 of the 500 members who joined the church were white (247).

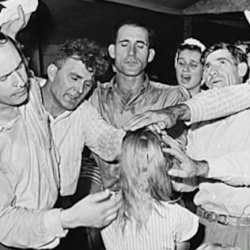

All that changed around and after the Civil War. The formation of separate black denominations was “largely a movement of self-assertion on the part of the oppressed” (261). When Richard Allen and his friends were forcibly removed from praying in a certain part of St George Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, they left to form an African Methodist Episcopal Church (260). A mixed church in Mobile dissolved and reorganized without black members, and so the blacks organized the African Baptist Church. Niebuhr sketches the various ways in which racial lines were drawn: “The series of steps from fellowship to schism includes complete fellowship of white and Negro Christians in the local church, segregation into distinctly racial local churches with denominational fellowship, segregation into racially distinct dioceses of conferences with fellowship in the highest judicatories of the denomination, and, finally, separation of the races into distinct denominations” (253).

The result was a precipitous decline in black membership in mainline churches: “Of the 208,000 colored members in the Southern Methodist Church in 1860 only 49,000 remained in 1866.” At the time Niebuhr wrote in 1929, 88% of blacks were in black denominations and most of the blacks in mainline denominations were segregated into African-American conferences. Instead of healing, racial divisions within the church were, he argued, starker than ever (258-9). Niebuhr notes, “The color line has been drawn so incisively by the church itself that its proclamation of the gospel of the brotherhood of Jew and Greek, of bond and free, of white and black has sometimes the sad sound of irony, and sometimes falls upon the ear as unconscious hypocrisy.” More hopefully, he suggested that “sometimes there is in it the bitter cry of repentance” (263).