In a number of places in his writing on Pentecostalism, David Martin refers to a musical variant of the “Halevy thesis,” Elie Halevy’s argument that the evangelical revival that birthed Methodism was the framework within which English religion and culture developed during the 19th century.

Martin’s variant is a musical Halevy thesis, which he applies to Pentecostal music in Tongues of Fire: “The power of music is . . . an influence toward social harmony. Music is anciently credited with charms ‘to soothe the savage breast.’ A Woodstock is as much a harmless release as it is an incitement to change the world. Above all it unites across boundaries, Perhaps one should say that music initiates precisely the kind of potent cultural change initiated by religion, and in much the same way slowly corrodes the outer forms of social structure.” In Latin America, Pentecostal music is so powerfully successful that “Pentecostals actually accuse Catholics of attending their services in order to steal their musical clothes’ (175).

He cites a study of the Chol area of Mexico that argued that “music is the most powerful of all agents for the propagation of ‘the gospel,’ so much so that in the Chol country . . . believers were labeled ‘singers’ by their irritated neighbours. . . . Next to the healings it is the rhythmic music and hand-clapping of the Pentecostals that provides the biggest attraction. When the Presbyterians cling to the older more hymnic styles and quieter kinds of service they lose ground to the Pentecostals” (176).

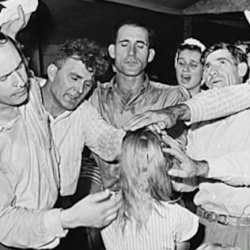

To italicize one point: Martin highlights the way Pentecostal music – music in general – can poke holes in social boundaries. Joined in music and dance, class and racial distinctions dissolve as everyone becomes one as they become one with the music.