Writing in 1961 (Is Christ Divided?), Lesslie Newbigin observed that while it is “common to say that we live in an age of revolutionary change,” it is uncommon “for Christians to welcome this fact.”

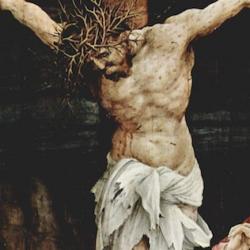

Newbigin thinks that’s a mistake: “we should welcome it—not merely because of the challenge which it offers to any man of faith and courage, but because it is precisely what our Lord led us to expect.” He came to cast fire to the earth: “Did anyone really think that so revolutionary an event as the preaching of the Gospel of a crucified Messiah could fail to produce revolutionary effects?” (26-27).

He sees the shock of the gospel in the turmoil of post-colonial Asia and Africa: “It is not accident that the newly-liberated people of these continents, having thrown off the colonial tie, do not and cannot go back to the conceptions of human life, of government, of human rights, with which the white man found them. It is no accident that they think now in terms of fundamental human rights, of human dignity, of the welfare state, of freedom from want and fear and the other ills of the world” (27).

Even the messianic character of Asian and African politics is a sign of the Gospel’s work: “Once He who is the Alpha and the Omega, the true origin and the true end of human existence, has appeared, human life can never be the same. It can never return to the static or cyclical patterns of man’s pre-Christian history. When Christ has come, men and nations must either give themselves to Him, their true Saviour, or else follow those who offer salvation on other terms. . . . All history converges upon that choice—the history of every man, and the history of the world” (28). Jesus or unbelief. Christ or Anti-Christ. Once Jesus comes, those are the only two choices, and, through the successes and evils of colonialism, Jesus came.

Newbigin places the Cold War too within this larger framework. If we grasp history in the light of Jesus, “We shall not allow ourselves to be so obsessed by the fear of communism that we can see nothing else. Communism is not the author of the revolution of our time; it is one of the movements which exploits it; the revolutionary movement of our time has deeper roots and a wider meaning that communism understand. . . . The penalty of allowing our judgment to be controlled by the fear of communism is that we may find ourselves defending injustice against the human cry for justice, and tyranny against the cry for freedom. . . . If God has permitted communism to gain a measure of world power and thereby to threaten our security, that is for His own good reasons. He knows what we need. Our concern is with something far more glorious and far more terrible than anything which any earthly power can either promise or threaten. We have seen the on real crisis of human history, the Cross” (29-30).

Newbigin’s wise counsel isn’t confined to the ferment of the early 60s. We should always evaluate the world in the light of the Gospel, which will deliver us “from much of the anxiety which we find around us. We shall not ask, ‘What is coming to the world?’ because we know Who is coming. We shall not think of our task as one of trying to hold back the revolution of our time, but as one of bearing witness within that revolution to its true meaning” (29). In brief: “For civilizations as for individuals, the beginning of wisdom is to fear God more than we fear death or disaster or anything else” (29).