In his contribution to Pentecostalism and the Christian Churches, Waldo Cesar calls attention to the spatial connection of Latin American Pentecostal churches with the urban streets of Latin America:

“There is nothing special from an architectural point of view, and in many cases large movie theater, rented or bought, which do not even have the appearance of a church, are meeting places. . . . The link with the street is achieved by means of a large facade, usually a long stairway establishing a certain territorial continuity, an invitation for free entry. The flow of the multitude entering and leaving repeated in the succession of several worship services on the same day, reminds us of the incessant walking of people on the sidewalks. The sidewalk seems to extend up to the church, a place of refuge and for the renewal of strength so that the worshipper can go back to the daily routine. Men, women, and children walk naturally between the public and the religious space – and the distance between the one and the other is transformed into a bridge, into a relation not always experienced in other churches or regions” (19).

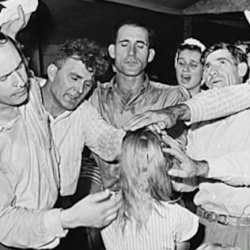

All sorts of people cross the bridge: “The human gathering inside the churches, aesthetically closer to the poor classes, resembled the diversified composition of the profane world, including drunks, prostitutes, drug addicts, and homosexuals – who do not feel rejected in the sacred space” (68).

As the language his this last comment indicates, Pentecostal churches tend to erode the sacred-secular dichotomy that is characteristic of many traditional churches: “the antagonism between Christian faith and secular life, so marked in the history of the church – and in Pentecostal fundamentalism – is overcome or at least relativized by a mission that reaches out into the street, to the transformation of those passing by, whoever they may be, into new creatures” (18). The blurring of the sacred/secular division is evident in Pentecostal teaching, in the emotionalism of its worship, in its music, in mission and vocation. It is the priesthood of believers brought into reality.

When a pastor speaks about oil and wine, he isn’t talking about sacred elements to be used on Sunday. Rather, “This discourse creates a ‘relation of equivalence’ between faith and life and offers a contextual dimension that goes beyond the circuit of the mere relation between the speaker (the preacher) and the listener (the believer). And so we can speak about another type of antagonism between what was and what is going to be. This means, once more, that the traditional line separating the sacred space and the profane world is broken by the word” (50).