In an interview with Image magazine, Rowan Williams explains the at of trust that is inherent in writing poetry:

“Poetry is always a risky enterprise. You don’t know where you’re going when you start writing. One thing you do know is that you’re not going to exhaust what you’re talking about; the willingness to take the next step, to put the next word down, is itself an act of faith. You know you’re not going to encompass it, conquer or control it. That’s what makes poetry an act of faith. One thing that interests me is the way this image of faith or trust is shot through all our use of language: The trust that I am understood. The trust that I will discover something by speaking. By listening. The trust that our words are not, as some philosophers would like them to be, games in the dark. Faith is implied in the very fact of the difficulty of the task: you know that you are going to find something there but you never quite manage it. I can’t make sense of that difficulty we experience without the sense that our language is about something. It’s not just choosing what we want to say. That’s why difficulty, I think, is one of the most positive things in language, and poetry which is deliberately working to make language more difficult, for the writer and for the reader, is actually doing us a great service. We must remember, it’s neither a game nor a simple labeling operation. It’s neither arbitrary nor controlled. Somewhere in between is this great, luminous darkness where we are risking the words that just might pierce that darkness.”

Poetry is also an act of faith because it involves listening: “When you write, you don’t simply put things down. You listen. When I talk to people about the experience of writing, quite often I tell them that there are some poems that walk in and sit down. You hear them coming in. It’s a dangerous metaphor, but you almost channel them. Then there are others where you have to listen and listen. It takes forever for things to assemble around the core. There may be moments when, for whatever reason, the channels are cleared, and something is so powerful and overwhelming that the appropriate poem streams in.”

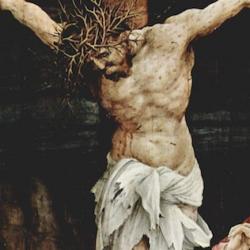

Successful art involves making something that possesses “the solidity, the claritas, in the medieval sense, the radiance, the luminosity, the density, of real things. The poem, the music, the visual artwork has that density that says that the world is full; the world is not empty; the world is packed.” An artist aims to produce “a reality that is charged, that is present, and that passes the radiance on to another level.”

Against this background, Williams complains that some religiously motivated artists work in unbelief. They don’t trust the material to make their case, and so turn their art into religious propaganda. Williams advises the believing artist to work out of faith in the truth of the gospel: “if you really believe that the kingdoms of this world become the kingdoms of our God and of his Christ, and not the other way around, then you ought to be more relaxed than otherwise about these things. More ready to let the meaning happen.”