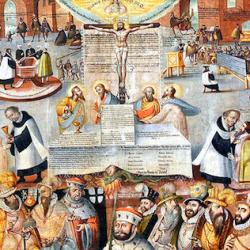

Sophie Read’s Eucharist and the Poetic Imagination in Early Modern England examines six early modern English poets on the assumption that “particularities of belief can be made manifest in the verbal texture of a literary work: that there is an analogy between the rhetorical and theological plans of understanding, and that their relation can be traced quite precisely. The most characteristic figures or tropes in a body of devotional poetry in this period are often used to express a conception of the mechanics of the eucharistic transformation, even when that is not the explicit point on which a poem meditates. Because the incarnation (word made flesh) and its liturgical re-enactment (bread made body) are fundamentally concerned with the power and possibilities of language, they exert a compelling imaginative pull.” Because “Protestant sacramentalism privileges the figurative,” the eucharist can be “a model of rhetorical expression” (38).

Read’s description of Protestant figuralism will raise some howls of protest from Lutherans, and her more detailed discussions of eucharistic theology leave something to be desired. But she’s a careful reader of poetry, and teases out subtle eucharistic/sacramental patterns and images. Donne is easier game in some respects, since he left behind eucharistic sermons where he explicitly lays out a Calvinist view of the real presence, steering between two “dissolutions” of Jesus: “there are other dissolutions of Jesus, when men will . . . mold him up in a wafer Cake, or a piece of bread” and another “annihilation” when “Men will make of him, and his Sacraments, to be nothing but bare signes” (quoted 74). He affirms a form of transubstantiation, not of the bread but of the soul of the recipient: “There is the true Transubstantiation, that when I have received it worthily, it becomes my very soule; that is, My soule growes up into a better state, and habitude by it, and I have the more soule for it, the more deified soule by that Sacrament” (quoted 75).

This receptionist, communicative view of real presence is behind Donne’s talk of letters as “sacraments of friendship.” Donnes writes, “It is a sacrifice which though friends need not, friendship doth; which hath in it so much divinity, that as we must be ever equally disposed inwardly to do or suffer for it, so we must seose some certain times for the outward service thereof, though it be but formall and testimoniall.” Letters communicate presence across absence, like the eucharist. As Read puts it, “the real presence of the writer is guaranteed to transcend distance and even death by a folded paper which takes on transubstantiatory powers of reconstitution and reembodiment” (76). Donne thinks that letters can do what physical presence cannot. Writing a letter in verse to Henry Wotton, he says, “Sir, more then kisses, letters mingle Souls, / For thus friends absent speak” (77). Toward the end of the letter where this verse appears, Donne claims that any guidance he has given to Wotton is just the reflection of Wotton’s own wisdom back to himself. He concludes with a punning flourish, focused on his own name: “But if myself I’have wonne / To know my rules, I have, and you have DONNE.” Read nicely glosses this with: “This enacts the unity it describes by making one word bear two meanings. If he has understood his rules, which are of course Wotton’s rules, then they have both finished (done”: he has ownership of himself, and Wotton has ownership of him (DONNE).” The very form of the lines suggests a sacramental union of sign and thing, of meaning and meaning. Read continues, “The rhyme fractures its twin, too: ‘wonne’ is also ‘one,’ and again the two men share the space of a word. Here Donne’s syllepsis manages to transcend the isolation of the individual in a way that is profoundly analogous to the spiritual effects of communion. This verse letter becomes a successful sacrament of friendship, sealed by what must be more than a phonetic coincidence to Donne” (77).

Donne’s love poetry suggests a more anxious response to questions of sacramental presence and absence. On the one hand, Donne knows that the communion lovers long for is communion in bodies: “Loves mysteries in soules doe grow, / But yet the body is his booke” (quoted 80). Yet the poems are haunted by the persistent fear that the bodily union is a bare sign: “Donne invokes the whole spectrum of sacramental belief to try for an expression of faith that will transcend absence, but it is the deluded lovers, besotted or rageful, that turn out to be the best Catholics. There is an insistent sense that the kind of incarnationalist sacramentalism they seek always threatens to subside into the merely figurative, whether they realize it or not, and the written nature of the sign is implicated in this feared failure. The lovers’ rhetoric fluctuates between thinking itself truly transformative and a series of empty signs” (82).