Henri de Lubac’s Corpus Mysticum is a densely detailed study of the changing punctuation of the medieval theology of the triple body of Christ. “Body of Christ” has a threefold significance: His historical body, in which He lived, died, and rose again; His sacramental body, the bread of the Eucharist; and the ecclesial body, the church.

Early Eucharistic theology presumed this punctuation: [Sacramental body – Ecclesial body] / Historical body. That is, the focus of theological reflection was not primarily the relation between the sacramental and ecclesial body, on the premise that the Eucharist made the church (“we are one body because we partake of one loaf”). The historical body was present in the sacramental body, and Jesus’ work in His historical body was the foundation of both the ecclesial and sacramental body. But the connection between the sacrament and the church was equally or more significant.

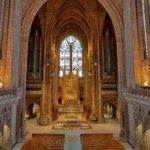

By the end of the middle ages, a new punctuation had shifted: [Historical body – Sacramental body] / Ecclesial body. Here, the link between the historical and sacramental body is the key issue: How is the Christ who was incarnate, lived, died, rose, and ascended, present in the sacramental body? The fact that the sacrament was at the center of a gathered ecclesia was no longer the main concern of Eucharistic theology. This new punctuation was reflected liturgically: The ecclesia stood at a distance watching the priest consecrate the bread so that the sacramental body became the very substance of the historical body.

The Reformers rejected transubstantiation and attempted in various ways to restore the older punctuation. They castigated the Catholic church for celebrating masses that excluded the laity. In the long run, though, Protestant sacramental theology and practice retained the late medieval pattern. Theologically, the relation of the historical and sacramental body continued to be the critical, and divisive, question; that was the question that divided Zwingli and Luther, despite their common conviction that the sacramental body was for the ecclesial body.

Practically, as James Jordan pointed out to me, many Protestant churches ended with a slightly modified version of the late medieval mass. In theory, no believer was to be excluded from the Supper. In practice, many Protestants refused to participate, thinking themselves unworthy to draw near. They end up in the same position as a medieval cathedral congregation, watching from a distance as elite believers receive the holy meal.

In part, this practice violates Protestant (largely implicit) theologies of threefold body. Yet, the heavy emphasis on the penitential requirements of participation, the stark somberness of some Protestant liturgies, have contributed to this result.

Protestants haven’t, in short, practiced a fully Protestant Eucharist. We have never quite escaped the distortions of medieval theology, liturgical practice, and Eucharistic piety.