Half a mile, not more, separates 50th Street and Park Avenue in central Manhattan from the northwest corner of 42nd Street and Seventh Avenue. But the two points mark the antipodes of New York City’s axis of religious dedication: to timelessness at one pole, to change at the other.

On the 50th Street corner stands the community house of St. Bartholomew’s Protestant Episcopal Church, one of a small complex of structures and handsome open space covering the entire Park Avenue frontage of the block north of 50th Street. The buildings include a 1920s version of an eastern basilica, a cloistered walk, and a garden space as well as the community building.

On the 42nd Street corner there’s an excited woman with a microphone in her hand, a loudspeaker behind her, and a few pedestrians in front briefly hypnotized by the voice that comes from the box on the pavement. The cone of speech uttered from the box is, so to speak, her nave; the microphone her pulpit. The woman wrestles, orally, with the devil. “Do you think you can go on with your evil ways?” the challenge issues hoarsely across sidewalks and streets for the edification of Satan’s presumed followers. “Jesus said there would be earthquakes, fires, damnation to cleanse the vileness of the flesh. Your flesh. Do you think God does not notice what you do with your body? You think He does not know the difference between good and evil and remember how you try to drag others down in the foulness of your ways?” An Hispanic accent intensifies the urgency in her voice, suggesting that on the brink of doom she could not wait to Americanize her speech. At this moment her listeners must either fall on their knees in repentance or flee from disaster. But attention wavers as the traffic lights change, and the obligation of staying alive in the city takes over.

Back on Park Avenue, in St. Bartholomew’s, a different struggle, equally earnest but inaudible to the passerby, has just ended. The adversaries here were two groups of parishioners. On one side the rector and his vestry and a majority of the present parishioners: they wanted to lease the site of the church’s community house to a builder who proposed to demolish the present community house and construct a large office building on its site. He would have allowed the church itself an indoor substitute for a community house in the new building––more spacious, modern, and, the rector’s adherents claimed, more suitable for carrying on what they describe as religiously inspired good works. The proposal also gave the church the right to participate in the rental income of upper floors in the office building, enhancing its ability to restore the remaining structures of the St. Bart’s complex, including the sanctuary itself.

Their opponents, including former vestry members and communicants as well as a well-behaved but emotionally roused company of outsiders whose participation reflects their devotion to good architecture and city landmarks, believed that maintaining St. Bart’s buildings as they stand is the most relevant good work of which this, or possibly any, urban church is capable.

The New York City Landmarks Commission, exercising its statutory powers of architectural preservation, refused to allow demolition of the community house. St. Bart’s appealed, and the matter wound up in the courts. It is ironic that the architecturalists, many of whom are on other occasions outspoken admirers of the First Amendment’s metaphorical wall of separation between church and state, supported the city’s right to analyze the books and financial records of the church in an effort to determine whether, by cutting salaries and activities other than building maintenance, the church might be able to afford necessary structural repairs and improvements without invading on a major scale the capital it accumulated from donors and testators in years gone by and with the earnings of which it tries to balance its present budget.

In any case, the architecturalists carried the courts with them. The U.S. Supreme Court declined in early March to hear an appeal from a ruling of lower federal courts that New York City has the right to make the church use its resources to maintain its buildings as directed by the Landmarks Commission because the congregation failed to prove that its present community house is no longer satisfactory for the congregation’s proper religious purposes.

This decision was consistent with a ruling in an earlier case by New York State’s highest court. That decision, involving the building of the Ethical Culture Society (which the state court, perhaps generously, classified as a religious institution), held that refusing permission to alter or demolish a landmarked religious building was not an unconstitutional taking of property or denial of rights so long as the building could still be used for its original purpose. That ruling (and the major costs of professional services that disputes over landmarking impose on a religious body challenging it) stimulated resistance among a wide spectrum of denominations. In effect, the Ethical Culture decision could foreclose the possibility that growth in an institution, or change in its surroundings, might force a religious institution to realize the value of its property to pay for a new building, perhaps in a different place, in order to fulfill its religious duties as it sees them.

The centrality of the landmarking of churches and synagogues to the role of religion in a major city is indicated not only by the hundreds of thousands of dollars spent on lawyer’s fees by St. Bart’s and its opponents, but by the supporting briefs, amici curiae, filed on behalf of twelve religious bodies ranging from the New York State Council of Churches to the New York Board of Rabbis. Supporting briefs were filed also by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York and Brooklyn and the New York State Catholic Conference; by the Church of St. Paul and St. Andrew (a New York church also involved in a landmark dispute); and by the Council on Religious Freedom.

When the New York City Landmarks Law, one of the nation’s earliest if not its first, was proposed in the early 1960s, public attention was drawn immediately to a possible impact on private, profit-motivated ownership. Even the law’s strongest boosters recognized that there might be problems of constructive confiscation if the proposed law forced an owner of real property to forego, without compensation, the right to alter or demolish a building because it had been designated a landmark.

While zoning also restricts owners’ rights to deal with their property as they choose, it does so on a different basis. Zoning restrictions on the use of private property are based on safety and health considerations and are enforceable as an exercise of the police power of local government. To be valid, a zoning law must be drawn in conformity with a general plan for conserving the community’s health and safety by prescribing land usage. Such a plan must cover every parcel of land under the jurisdiction of the government with police power.

Landmarking a building for its historic or cultural value stretches the police power beyond its traditional limits of protecting public health and safety, and then stretches it still further. Landmarking does not depend upon a plan that affects every parcel of property. It affects only those buildings that happen to be older than the statutory minimum age and that possess certain attributes, not previously identified, that led the members of a commission to designate it a landmark. That decision is inevitably more personal, less objective, than the mathematically expressible standards of a modern zoning law.

In response to objections and in order to provide at least minimal equity, the law finally included a hardship provision, subsequently revised, stipulating that if an owner could not, after being landmarked, earn a 6 percent return on the assessed value of the property, and if the Landmarks Commission could not find a way to assure such a return, the landmark designation was voidable.

While that gave some relief to profit-motivated owners, it soon appeared that it offered nothing at all to any owner who was not motivated by financial considerations. Thus the law denied statutory relief to educational institutions like private schools and colleges, cultural institutions like museums, and all religious institutions. No statutory standard spells out the nature of a hardship imposed on such a non-profit owner that would entitle him to alter the appearance of or demolish the structure.

Owners of such properties have consistently complained that lack of a hardship standard applicable to their landmarked properties is unfair, especially since the Landmarks Commission has demonstrated a tendency to landmark what they claim is a disproportionate number of religious buildings (95 of 600 as of 1986).

Supporters of the Landmark law have opposed such owners consistently. Some have argued that showing special favor to owners of religious buildings would constitute a breach of the same wall of separation that they, or others on their side, have not hesitated to ignore when it comes to governmental inquiry into how the religious institution spends its funds. Others have not found such disputation necessary. They merely point out that if ecclesiastical architecture were given an escape clause on the grounds of hardship, New York City would lose a lot of good old buildings. The possibility that, unless a hardship clause were inserted, New York might lose a lot of good old congregations does not seem to bother them. Nor are they troubled when it is pointed out to them that, if we are to compare the values imputed constitutionally to religion and architecture, religious activity is protected by the First Amendment while nothing anywhere promises architects freedom from government restraints, about the proliferation of which architects are often heard to complain.

Even though they do not seek to make a profit, the hardship issue often arises for churches, synagogues, and, presumably, mosques and temples because of the rapid changes that characterize settlement patterns of urban residents. Devotion to a religious institution rarely determines a family’s choice of neighborhood. As the character of an area changes, families move, leaving their homes to new arrivals, probably of another economic status and perhaps of a different religious persuasion. The religious institution to which the movers belonged may lose so many members that it finds itself forced to sell land and buildings and move on, using the proceeds of the sale as foundation for a new structure in a likelier location. A landmark designation tends to block this progression. Only a limited number of buyers want to take over an aging house of worship that, under the landmarks law, can be turned into a discotheque on the inside but cannot be demolished or changed in its exterior aspects, not even to allow a sign warning or promising strangers that, despite appearances, they are unlikely to find worshippers inside.

Nothing in the law compensates the non-profit owner for the loss in resale value that can follow from permanent landmark restriction on the future of the land. Nor, in most cases, is there any provision for financial help to keep the building’s unique but, to the religious owners, perhaps superfluous ornamentation in the state of repair demanded by the Commission to sustain landmark quality.

Brent Brolin, a New York architect and architectural critic, author of The Battle of St. Bart’s, a book-length account of the fight over that church’s landmark status, is one of the few landmark enthusiasts who offers an excuse for lack of a statutory provision of hardship relief to non-profit owners of landmark buildings. He claims that case law, made by judges in the courtroom, is an adequate substitute for statute law. If that were true, the statute would not have had to include hardship relief for profit-motivated owners as it now does. Brolin may have forgotten that higher-court decisions are binding only on the courts directly below them, and then only when the facts of the earlier decision are congruent with those in the case before the second court.

All in all, the rejection of statutory hardship protection for non-profit buildings reflects the view of contemporary legislators and jurists, perhaps influenced by the widely asserted beliefs of landmark enthusiasts, that in a democratic society local government is competent to define the primary obligations of a religious body within its boundaries.

It is possible that landmark enthusiasts are inspired not only by the aesthetic qualities of fine architecture but by their symbolic representation of religious doctrine. That would adequately explain devotion to saving, intact, structures of the quality of, let us say, Mont-St. Michel or King’s College at Cambridge University. The present St. Bartholomew’s and its community house may be the best early-twentieth-century adaptation of Eastern European sacred architecture that the city of New York could produce, but it seems unlikely that it is capable of inspiring the same religious awe that earlier expressions of almost total unity-in-faith are able to inspire even in skeptical modern visitors.

Old-time New Yorkers familiar with the city’s ecclesiastical rivalries suggested that, far from celebrating unity in Christendom, the choice of a Byzantine architectural vocabulary for St. Bartholomew’s shrine—only two city blocks east of St. Patrick’s Roman Catholic cathedral—could have been intended as a gentle extramural reminder to the latter’s communicants that large sections of what was the Papal See are now closer to Anglican theology and practices (and thus to America’s Protestant Episcopal Church) than to those of Rome.

None can question the power of great religious architecture to inspire awe. Nor doubt that in certain historic periods when the unity of faith dominated men’s consciousness that awe was energized not only by such a building’s symmetry and grace but by its reflection of the perfection and the timelessness of God. As a state of being, timelessness is a concept so difficult to grasp, at least by Western minds, that architects have tried to render it symbolically, a stone steeple reaching into a cloudless sky. Or, as in the case of St. Bart’s, by a dome, the perfect three-dimensional figure in that every point on its surface is equidistant from its source at the center. Unfortunately, the dome went up some years after the rest of the St. Bart’s complex was finished, and it was made nearly invisible by a surge of skyscrapers to the East, North, and South of it, long before the passage of the landmark law.

It need not be assumed that those who wanted to prevent changes in St. Bart’s sought to save it for its religious connotations. On the contrary, they often give the impression that they are truly comfortable in a religious building only when satisfied that no one will be able to embarrass them by experiencing religious awe in their presence. What they seek from landmarking is reassurance that there are limits to the physical and moral changes they will have to experience in their own lifetimes. There is nothing trivial nor shameful about hoping for such a consummation, but turning from Park Avenue, where religious emotions are fixed on conserving the present, to listen more attentively to the street preacher on Times Square, is to find that God’s timelessness is important because it offers men and women a lasting direction for change.

The street preacher, struggling against the ambient noises of urban life, her audience distracted not only by noise but by the trickle-down aestheticism of the times, is not, of course, arguing for change in the structure of the city’s buildings, but change in the hearts of her listeners, in their faith and then, perhaps inevitably, in their behavior (an obsolescent term connoting “lifestyle”).

Between Park Avenue and Times Square one can imagine a continuum including each of the city’s religious institutions, of whatever faith or sect, age, or condition, ranked on a scale that measures which of two fundamental postulates of religion—the timelessness of Divinity and the malleability of man—is more important to its congregation. And shaping their messages accordingly.

The street preacher speaks to people whom she understands to be lost. Not lost in the Park Avenue meaning of adhering to the wrong view of architecture, or, as in too many of the religious institutions on the continuum, because they adhere to the wrong politics, but lost to God, to virtue, to life everlasting. Her mission is to recall them from the depths, reclaim them to face the moral life, free them from the evil forces that have them in their grasp.

II

Such have been the motives of what one might call the street religions of the great cities. At times they have existed as a separate branch, a special order within the walls of the established churches and synagogues, only to discover that a common book of prayer was not always enough to overcome the differences in doctrine and practice between the old and the new.

Sometimes street religions were successfully absorbed by the older structures—organizational as well as architectural. Sometimes, as most remarkably in the cases of what became the Lutheran and Methodist churches, despite the wishes of the original leadership, what started as a mission to revive original commitments of the older institution became a movement to leave the older church altogether.

Although religious inspiration, reaching a level of hysteria at times, can be found on the street or in a storefront, religion is more than moments of inspiration. Street religions lack the sustaining power that fellowship and institutionalization, in the proper circumstances and with the right leadership, can provide. Especially in the current atmosphere, when moral arguments that depend on the acceptance of timeless truths are suspect, and when racial and political explanations of some aspects of human behavior are too often accepted as explaining all of it, constant reinforcement of personal commitment is essential to produce a lasting change of behavior. Yet there are examples of street-corner religions that have become sufficiently institutional to make the initial appeals effective over a long period.

Currently, the street preachers in the cities who attract notoriety and a following that makes up in fervor for what it lacks in number are most likely to emphasize racial and political conflict. But half a century ago, a notorious New York City street preacher attracted thousands of devoted followers and established a remarkably strong institutional base with a message that was substantially apolitical, though over a period of years he collaborated informally (according to his biographers) with the Communist Party. His preaching stressed behavioral values associated with the Judeo-Christian tradition despite the fact that we must conclude that his own conduct was at best heretical, at worst blasphemous. His name was George Baker but he was more often known as Father Divine (1880-1963). That he was literally a divinity and thus immortal was explicitly accepted as truth by his followers.

The overwhelming majority of them were black people with little education, but they included white men and women, some with college degrees and some who abandoned spouses and children to live in one of his residential “Heavens” (Divine/Baker’s term). These were sexually segregated dormitories in urban centers like Harlem, Newark, and Philadelphia, acquired with funds contributed to Divine/Baker by his followers and admirers. Conditions in the Heavens were neat, clean, and cheap, and the food generous in quantity.

Divine/Baker asked in return only that the faithful turn over to him all their earnings from outside work and all their accumulated capital. Even more demanding was his insistence on rules of behavior that stressed the bourgeois virtues of sobriety, honesty, cleanliness, and reverence, as well as some norms more consistent with the patterns of extremist sects, including total sexual abstinence even for married couples and the abandonment of normal family responsibilities, such as responsibility for the upbringing of children.

During the Depression, when Divine/Baker flourished, the bargain was a good one for both sides. Divine/Baker’s followers found peace and security when neither was readily attainable by black Americans. These social goals were reached with the help of ingenious (and extremely conservative) management skills exercised by the Divine/Baker and his aides in investing contributions from the faithful and enforcing the rules.

Divine/Baker and his closest associates lived in the same buildings as other communicants, although with access to better suites of rooms, finer clothes, automobiles, servants, and, in the case of Divine/Baker himself, the services of twenty-four secretaries.

Anyone who claims to be God, as George Baker did, and who ultimately is proven not to be, must either have been grossly misinformed by himself or others, or was from the start a self-conscious mountebank. It seems most likely that Baker belonged in the latter category, but his biographers, Sara Harris and Harriet Crittenden, who were certainly not disciples, believe that despite this egregious and fundamental flaw of insincerity, he was scrupulously honest in his financial practices. They tell readers that the Heavens were held in the name of groups of individual Angels (otherwise known as members) and none of the income inured to the taxable benefit of Divine/Baker. Despite audits of his books by the Internal Revenue Service, to which he never, according to the same sources, paid a penny in income taxes, its agents were unable to charge him with tax evasion. That at least was the case when Harris and Crittenden compiled their biography (Father Divine: Holy Husband, 1953).

It may appear ridiculous to waste time in searching the record for useful apologetics for Divine/Baker. To put matters mildly and simply reject his self-attribution of divinity as spurious, a fair-minded observer must acknowledge that he was not simply a swindler, that his influence on his followers was effective and, whatever this statement may do to common conceptions of ethical behavior, even constructive.

Drawing a majority of his followers from the worst off of the black migrants who came north in troubled times, Divine/Baker devised a program for restoring egos shattered by a lifetime of discrimination and a new crisis of poverty. He broke the color line in living accommodations when not even the United States Army dared to try to do the same. He made each follower start a new life by taking a new home; treated each as his own direct offspring and therefore similarly touched with divinity; demanded that each live up to an exemplary code of self-denial, not only in the sexual mores that attracted widespread attention but in commercial transactions. He resisted the argument that because people of color had been discriminated against they should be excused from observing the same scrupulous standards as the pillars of society.

A curious demonstration of effects and shortcomings of this last rule may be found in a publication regularly distributed to Divine/Baker’s followers and friends. The journal contained copies of letters exchanged between members of the movement and officials of some of the nation’s largest and busiest companies.

Each such exchange begins with a letter from a Divine/Baker follower to, for example, the treasurer of a major railroad. It explains that the writer, a follower of Father Divine, on a certain day some years previous, traveled between two points on the railroad without having bought a ticket. Enclosed please find a postal money order reimbursing the company for this dishonest act, sent at the behest of Father Divine himself who, characteristically, extends “best wishes for (the recipient’s) health in every cell, fiber, tissue, bone, atom, molecule, and vessel of (your) bodily nature and with every wish for good health and good cheer.” Then the signature of the repentant sinner.

Printed below each such letter was the response from the official to whom the original had been addressed. Dear Henry, it begins; or Dear George, or Dear Sarah, but never Dear Mr. or Miss Jones. To present-day readers, the demeaning salutation conveys a long and melancholy story. It reminds us that years would pass before white America would be prepared to recognize Negro Americans to be entitled to natural acceptance as equals, no matter how long and faithfully Negroes endeavored to conform to the code that Father Divine prescribed as opening the path to full rights.

Divine/Baker’s insistence that no one could take away from the child of God what He had implanted shielded the person of color from having to notice the “Dear Henry” snubs.

That shield was the product of an extraordinary psychological device. Divine/Baker was able to inculcate patience because he promised and inflicted prompt retribution against those who wronged him or his children. His secretaries regularly revealed to the faithful that some celebrated person who had just been described in the newspapers as encountering sudden misfortune was, in fact, the most recent victim of divine retribution for a most sinister offense against Divine/Baker or his followers. The retribution list included such punishments as sudden accident or illness or even death, especially death from peculiar and mysterious offenses, often of people whose offenses had been unnoticed until retribution caught up with them and which usually continued to be unspecified. While he never quite said so himself, Divine/Baker allowed his secretaries to allow his followers to assume he had arranged the retribution personally.

Divine/Baker is of interest because his success demonstrates that thirst for a timeless set of values and an orderly life remains even—or perhaps especially—in a modern city that has dehumanized charity, proclaimed relativism, politicized religion, and seeks nightly to televise the Book of Revelation as entertainment. While the established churches criticize these tendencies, Divine/Baker offered an immediate remedy: shedding an old life and entering a Heaven. That Divine/Baker was essentially a self-conscious charlatan reflects on his character, not on the motives of those who accepted at face value his assertion of his own divinity.

Those who had occasion to observe him in the presence of his followers suggest that his assertion of divinity was the more believable for the restraint in his performance.

He did not strut or posture. When a follower stepped to the microphone in one of his banquet halls to plead for divine help in overcoming some painful condition or disease, Divine/Baker characteristically paid no attention; he continued to eat his dinner or to wipe a spot of gravy from the lapel of his white linen jacket. Observers who saw him often felt that had he attempted to play the part of an all-seeing, merciful divinity, the fraud would have been easy to detect, even by the most gullible of his followers.

III

To recognize the way in which a street preacher who is as wise as he is inspired can affect his contemporaries, the character of religious institutions generally, and the definition of public morality for decades to follow, one should turn to eighteenth-century Britain and the life of John Wesley. Wesley managed to combine the emotional power of the preacher outside the church with the institutional continuity of the church itself. There are signs, in the formation of new religious revivalist groups with strong institutional tendencies in today’s cities, that a similar tendency is developing in the modern American city.

There is a basis for expecting a similarity between the religious movements that developed in eighteenth-century London and those that are emerging in contemporary New York. The similarity reflects striking resemblances between the two societies despite their separation in space and time. Both were troubled societies wrestling with the social and economic problems of massive change.

Eighteenth-century England was emerging from the premodern era with its traditional communal groupings in which conditions of geography, social status, religious affiliation, economic activity, and the level of education were homogeneous and rigid. In the new industrializing society, social groupings such as political parties, trade unions, common schools, fraternal organizations, and industrial corporations were just beginning to take shape. The one institution with any claim to a place in both worlds was the established church, the sole institution powerful enough to deal with social problems. Contemporary American society has now fairly exhausted the institutions that were conceived with industrialization, leaving religion (which now includes a multiplicity of separate institutions) once again alone as qualified to claim some measure of continuity extending from the past into the future. And with that continuity to claim the potentiality—not as yet fully realized—of confronting constructively the new problems of society.

Labor unions are declining in power as electronically controlled machinery takes over work formerly carried on by human workers collectively under a single roof. Broadening choice of a place to live and the incredible increase in the provision of personal mobility have undermined communities formed in the factory age, which themselves barely resembled the tightly woven small communities of the premodern world.

The word “community” continues in popular usage, but the human reality it purports to describe has been diluted until it gives off more of a nostalgic flavor than the reflection of a living reality.

Political parties have seen much of their power eclipsed by intervention of government itself in the problems of individual welfare. Fraternal organizations no longer prescribe codes of personal behavior, nor do they inspire group loyalty; they have become mere social clubs.

Most important, multiplication in the number of “authorities,” persons who purport to enlighten their listeners through mass communication technologies, has undermined the notion of authority altogether. Mid-rank figures—the policeman, the schoolteacher, the merchant in commercial transactions, the landlord who imposed on displaced sharecroppers the urban principle of saving money—collectively sometimes called the sergeants of society, have lost their badges of authority.

And so in the contemporary large city, religion remains practically the only institution capable of asserting moral authority, as was also the case in Britain’s eighteenth century. In both locales, however, the institutionalized church lost interest generally in questions of individual moral conduct. In eighteenth-century London, the new rationalism among intellectual leaders had produced skepticism of whatever could be derided as essentially superstitious. Among the nobility, new and old, churchmen were welcomed only when they shed the gravity that was considered offensive in a social order in which wit was king. In today’s New York, church leaders have grown impatient with the prospect of retailing an uncertain cure for human ills, while government claims to cure them wholesale, though hardly with greater certainty. Among the leaders of society, worship of aesthetics and nature have become triumphant ethical values, readily apparent in the victory of the church-as-architecture over the church-as-house-of-worship.

John Wesley was not the only revivalist preacher, in and out of churches, in England’s eighteenth century, and by most accounts not even the most effective in rousing emotional, sometimes hysterical, response among his auditors. Yet it was he who combined religious dedication with great organizational talents and a remarkably sensitive gift for what we now call public relations. He added a rare quality of sincerity and innocence that must account for his ability to disarm even violent proletarian opponents who threatened to maim, drown, or imprison him as an agent of the Pope of Rome and an envoy of the Devil himself. Equally determined Church of England bishops and vicars, curates, and laymen denounced him for a whole catalogue of ecclesiastical offenses against the established church, most damning of all, his excessive “enthusiasm.”

Yet in the end, Wesley, a man of less than average height, a tireless traveler, something of a plagiarizer, and a proud bowdlerizer of classic works which he distributed at cut rates among his followers, a political conservative who encouraged men to become wealthy (on condition that they share their gains with the poor), a fervent, premature abolitionist who was also an opponent of the tax-resistant American colonists straining to free themselves from the mother country, founded what has become in all probability the largest single Protestant church in the world: Methodism.

Two centuries later, Methodism itself is so firmly established in its own right as a part of the Christian orthodoxy that its revolutionary achievements in the eighteenth century are all but forgotten.

When Wesley emerged from obscurity by urging his listeners to expel the Devil inside them with the help of God, his nation was shifting from agriculture to industry as its principal wealth-producing activity. The change moved villagers and peasants from the countryside in which they had lived for generations and dropped them on the streets of the big cities. In the process, it alienated hundreds of thousands from their personal and institutional affiliations and demonstrated the feebleness of their attachment to the established church. Ignorant, untrained for the work they now expected to find, desperate for relief from hunger, disease, and simple fear, they, like many of our contemporaries in modern cities, became addicted by the thousands to a new form of an old drug; in their case, alcohol, in ours, cocaine.

The development of gin—a distilled spirit that can be drunk without aging—was as devastating as the 1980s invention of crack. Gin’s alcoholic content (more than 40 percent by volume as compared with less than 6 or 7 percent in fermented drinks like beer and ale) made swift, cheap response to alcohol inevitable. It created an instant market with tragic results even among women and children. By the mid-eighteenth century, there were said to be 17,000 gin shops in London in which customers could get a shot of gin for a penny, a full glass for two cents, and, for an additional penny, a straw sack on which to sleep off one’s drunkenness.

With the spread of alcohol, a new, sub-proletarian class formed in London, Bristol, Liverpool, and other exploding English cities. Families disintegrated. Crime, violence, disease, and general demoralization spread. Similar migration has had similar results in our own time.

Eighteenth-century London lacked a legal method for discouraging drinking. Its crime control depended on the inculcation of terror rather than the certainty of laying hands on every offender. Hanging or lifelong overseas exile for every felon who was caught, however trivial the charge, doubtless discouraged some prospective criminals but tended to deepen the demoralization of a large part of the population. John Wesley believed that a proper religious revival would counteract the temptations of gin and crime, but that without constant reinforcement the impulse to personal reform would lapse, no matter how striking an event the original epiphany might have been.

Preaching where he could, in churches if they would permit it, outdoors if they did not, in halls or vacated buildings as his movement started to grow, Wesley concentrated his evangelical revival efforts in the growing cities—London, Birmingham, Bristol, Liverpool, Manchester. The itinerant preachers he trained, the circuit-riding Methodist ministers, followed.

Yet Wesley differed from other evangelical revivalists by his recognition of the necessity of developing an organization of followers, groups in every city that would be open to members of every class of society. In these groups continuing emphasis, described by one biographer as imposed with almost military severity, would be placed on living the good, the blessed life. Prohibitions were many: No drinking of spirits. No gambling. No cursing. No idle frivolity or game playing. Sexuality restricted to marriage. Reading of Scripture and of serious texts, Wesley to supply the books. No gluttony.

Much as in the case of newcomers in the modern city, displaced agricultural workers in Britain’s eighteenth century left behind religious institutions, small parish churches with which they were familiar, and found themselves without churches that could serve them and their children when they reached the city. If it can fairly be said that many Protestant sects are currently turning out Mrs. Jellyby by the hundreds of thousands, trained to be more concerned with mass morality and international politics than with the condition of their families, it would be even more true to say that the established church in England in the eighteenth century was a decayed institution in which the occasional dedicated cleric was far outnumbered by political functionaries who owed their posts to influence and spent their time in avoiding religious duties.

John Wesley described his life’s work in these words: “We went forth to seek that which was lost, more eminently lost, to call the most flagrant, hardened, desperate sinners to repentance. To this end we preached in the Horsefair at Bristol, in Kingswood, in Newcastle, among the colliers in Staffordshire and the tinners in Cornwall, in Southwark, Wapping, Moorfields, Drury Lane, in London. Did any man ever pick out such places as these in order to find serious, regular, well-disposed people? How many such might there be in any of them I know not. But this I know, that four in five of those who are now with us were not of that number but were wallowing in their blood; till God by us said unto them ‘Live.’”

It is obvious that Wesley’s work did not redeem all those in the British Isles who were wasting their lives for reasons which they might have been able to bring under control. But it seems clear to chroniclers of the eighteenth century that Methodism had a palpable, if unquantifiable, effect in reducing the consumption and availability of gin, in stimulating the pride of the new working class, in moderating the excesses of eighteenth-century criminal justice, in helping to reestablish a greater measure of family stability after the shocks of migration from farm to factory.

All of these changes were effectuated by a combination of the direct, immediate, and overwhelmingly emotional experience of revelation and its continuing reinforcement by the structure of a religious institution. Surely it is not inconceivable that new religious leaders will rise in the city, to echo in their own words the Wesleyan claim of having restored life to the lost and purpose to the institutions of religion.

Roger Starr is a member of the New York Times editorial board and author of The Rise and Fall of New York City.

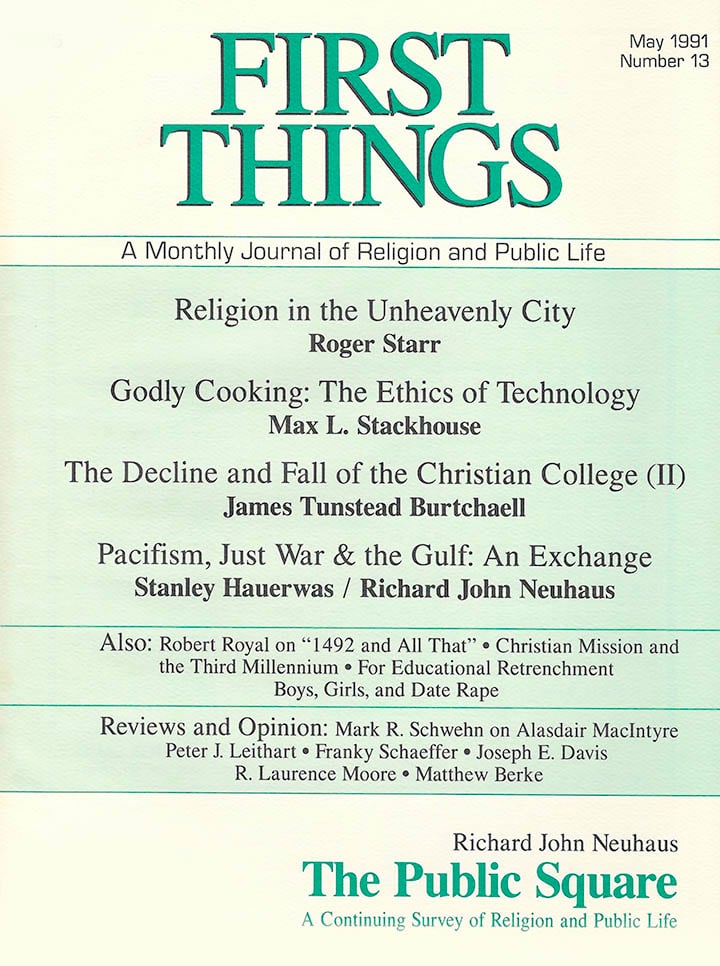

Photo by Elisa Rolle on Wikimedia Commons, licensed via Creative Commons. Image cropped.

What Vivek Gets Wrong About Citizenship

December is here. The air is chill, the leaves have fallen, and children are preparing for school…

Tucker and the Right

Something like a civil war is unfolding within the American conservative movement. It is not merely a…

Andrea Grillo and the End of His Usefulness

No one with any knowledge of Roman universities would be the least surprised to hear that Sant’Anselmo,…