The Old French word ordinarie, meaning “ordinary, usual,” derives from the medieval Latin ordinarius (“customary, regular, usual, ordinary”), which derives in turn from the classical Latin ordo (“row, rank, series, arrangement”). Originally, it had no pejorative connotations, but by the mid-eighteenth century, “ordinary” signaled inferiority in class, education, and taste. Daniel Defoe recalled from the year of the plague the “horrid oaths, curses, and vile expressions, such as, at that time of the day, even the worst and ordinariest people in the street would not use.” We think of the related word “common,” which may denote both “usual” and “vulgar,” though it also means “shared.” Ordinary people are uneducated or dull but also regular folk, the salt of the earth. In the latter sense, however unrefined they are, they participate in something larger than themselves, something held in common and altogether contrary to the monads of individualism.

The paintings of Vermeer, for example, are full of such quotidian tasks as sewing, preparing meals, and sweeping. The Lacemaker, his smallest work, shows the hunched figure of a woman whose hands form an exquisite architecture of fingers and bobbins. Vermeer focuses on the woman’s utter absorption, sets her against a blank wall with a blurred foreground, and draws us into her tiny, intimate world. The contemplative expression on her face suggests a rich and wordless inner life that is bound to the threads, lace pillow, pins, and bobbins with which she works. The care she devotes to her task ties her to the world she inhabits. Custom situates her, just as Vermeer’s painterly arrangement does. Custom and arrangement return us to some of the original history of the word “ordinary.” Yet there is nothing ordinary, in the pejorative sense, about this painting. What Vermeer reveals is how the extraordinary issues out of the ordinary.

The painting gives no hint as to whether the lacemaker thought of herself or her life as ordinary. We don’t know what she thought about herself at all. Would she even be bothered to be thought ordinary? Her competence with the tools of lacemaking is presented without commentary, as a matter of course. She was probably taught by her mother. I doubt she consulted a book in order to master the skill by which we remember her, because her life did not depend on distinguishing herself from others, or on making something of herself through self-improvement. Quite possibly, the only book that mattered to her was the Bible, where glory comes from being loved by God. Significantly, she has a small Bible or prayer book beside her.

The distinction thus divinely bestowed is what C. S. Lewis meant when he said, “There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal.” Lewis rejected what he called “the worship of the human individual simply as such,” the exaltation of personality as something special in itself, driven by the need to liberate one’s originality. It would be difficult to place the lacemaker within the modern obsession with singularizing the self. A member of a painters’ guild, Vermeer was to a great degree considered an artisan in his time. (He was an art dealer as well.) Lacemaker and artist alike were apprenticed, acquiring their skills in the family or the workshop. God, in this scenario, was not a guru of self-help.

In the nineteenth century, Americans thought of themselves as self-reliant, with Emerson’s “habits of self-help” their model. Earlier, Ben Franklin’s Autobiography had codified thirteen virtues, among them frugality, order, and industry, as the cornerstones of self-improvement and success. Though the roots of such advice are ancient and can be found in conduct manuals both for princes of the realm and for the not-so-princely, the first real self-help book was published in 1859. It was written by a Scotsman, Samuel Smiles.

Smiles explained why he wrote it: “The origin of this book may be briefly told. Some fifteen years since, the author was requested to deliver an address before the members of some evening classes, which had been formed in a northern town for mutual improvement. . . . Two or three young men of the humblest rank resolved to meet in the winter evenings, for the purpose of improving themselves by exchanging knowledge with each other.” This hugely successful book appeared in the same year as John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty and Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. It shares with them an emphasis on individualism and struggle—not the Darwinian struggle for life, but the value of striving amid hardship. The philanthropic-social aspect of the book, insofar as it arose from concern for working-class lives, should not be ignored, either.

Spain’s premier nineteenth-century novelist, Benito Pérez Galdós, is another example of the promise that even the meanest among us is capable of some form of eminence. The character who illustrates this point in his Fortunata and Jacinta is an illiterate grifter and would-be revolutionary. With his superb physique, however, he becomes a celebrated artist’s model, perfect for representing nobility and saintliness. Galdós’s other characters are bunglers and washouts from ordinary walks of life, yet they are hardly standard or dull. What sets them apart? Like Don Quixote, they possess a rich inner life ruled by the imagination. Even the bourgeois womanizer Juanito Santa Cruz, the least endearing of the novel’s characters, knows how to turn his deceit into a good story. Don Quixote, likewise, reinvented himself as he retold his personal history. The ingenious gentleman from La Mancha did not start out that way; his life was most ordinary until he was driven crazy by reading too many books about chivalry. You might say that he treated chivalric romances as early-seventeenth-century self-help books, guiding his perspective on life through one misadventure after another. The genius of Cervantes was to turn his character’s life into something extraordinary in the moment it became a walking disaster, as soon as it strayed from the straight and narrow into knight-errantry. An astonishing form of self-improvement, indeed.

At once exemplary and aberrant, Don Quixote has an aesthetic sense of himself. He takes the stuff of ordinary life and makes it into something else. He becomes his own story; in a word, he becomes art, not simply because Cervantes wrote him into existence, but because the character acts out a new script upon a most peculiar stage. That stage is so-called reality, though what a strange, unfamiliar reality it appears to us. Don Quixote himself doesn’t always see the strangeness. To the gentleman from La Mancha, those windmills really are giants that happen to resemble windmills. Enchantment is the norm. Only by working through his illusions (and his failures) does he acquire self-knowledge in the end.

The relation of the ordinary to the extraordinary depends upon this aesthetic sense. Nobody wants to be perceived as ordinary, but few have the imagination to avoid it. Obsession with celebrity and shortcuts to success have taken the place of the enchantresses of old, led by the most seductive siren of all, the image industry of mass media. Interviewed by Joe Hagan for Vanity Fair on running for president, Beto O’Rourke said, “I want to be in it. Man, I’m just born to be in it.” Spotting a stack of presidential biographies, Hagan wrote, “O’Rourke might be destined for this shelf. He has an aura.” The aura apparently was not powerful enough to carry him to the Democratic nomination in 2020, as he has already dropped out of the race. But maybe his chance will come during the next cycle. Destiny has its own timetable.

Is O’Rourke’s aura real or fabricated? Being photographed by Annie Leibovitz, who hypes celebrity, certainly helps. Almost nowhere in the Vanity Fair profile do we read of the man’s achievements, only his inordinate sense of personal destiny. Americans have seen this before in their politicians. Vanity may be a necessary element of the kind of personality who feels impelled to sell himself to voters. Anyway, we shouldn’t expect much from a human-interest story laced with political ambition. Hagan’s buildup of Beto does, however, tell us something about how political figures are portrayed as at once ordinary and extraordinary. Hagan threads the needle between hipster-outsider status and domestic grunge. Just the kind of non-ordinary ordinariness Gen Xers casually assume.

O’Rourke picks up his kids from school, makes Sunday morning pancakes, and goes barefoot in blue jeans and a T-shirt. But we also read of “the power of O’Rourke’s gift” at political rallies, something he calls “a near-mystical experience.” There, he said, “every word was pulled out of me. Like, by some greater force, which was just the people there. Everything that I said, I was, like, watching myself, being like, How am I saying this stuff? Where is this coming from?” Another word for this is spin. Or maybe magic. If Don Quixote blamed enchanters for the ever-changing illusions he encountered, can’t Beto explain his out-of-body experience as the work of the audience itself? The crowd’s emotional investment in Beto becomes a transformative act. The role of the crowd epitomizes the difference between a knight-errant and a celebrity. A knight sets out to do good, even a half-mad knight questing in imagined worlds; a celebrity thinks he already is good, awaiting only the world’s recognition.

In the end, Emerson wrote, “We cloy of the honey of each peculiar greatness.” What would he have thought about confected worth of the kind Jay Gatsby achieved, at least for a season? Or something more contemporary still: anticipated, as opposed to actual, achievement? Do we reward people for what they were “born” to do? Why, yes, we even give Nobel Peace Prizes to presidents barely in office. It shouldn’t surprise us, then, that wealthy parents bestow accomplishments upon their children by paying to have someone else take their SATs or photoshop them as buffed athletic bodies. Or that a New York Times article should tell high school seniors, already jaded after acceptance into the college of their parents’ choice, to “make themselves their senior project.” Heaven protect us from the affliction of appearing ordinary and, failing that, our cheerleading culture of self-affirmation.

Fetishized celebrity and aspirations to world-beating success are not new to American society. Self-Help, which exceeded commercial expectations well beyond Great Britain, made Samuel Smiles an instant celebrity. The popularity of such books in the United States reinforced the older ideal of self-reliance. But self-help guides also marked a new ideal, one that promised a swift and stumble-free path to distinction and attainment. Eagerness for self-help existed alongside a growing culture of celebrity in nineteenth-century America, suggesting a link between self-improvement and the promotion of personality. Americans were enthralled by Jenny Lind, the Swedish opera singer shrewdly promoted by P. T. Barnum. They flocked to Edwin Forrest and Junius Brutus Booth’s performances, and to Charles Dickens’s and Oscar Wilde’s lecture tours. What drew them was personality on display, fame and notoriety radiating outward.

This largeness of self is now seen as a universal birthright. Oprah’s latest book, The Path Made Clear, asks, “Do you believe that you are worthy of happiness, success, abundance, fulfillment, peace, joy, and love? What I know for sure is you become what you believe.” There’s nothing wrong with “discovering your life’s direction and purpose,” as the subtitle says, but boosterism of this kind has the shelf life of a Twinkie. (In case you’re wondering, it’s forty-five days.) This anticipatory praise of greatness within does not work, and for a simple reason: It disengages individuals from the social body, the common realm that is the nourishing soil of enduring personal qualities that rise above what is ordinary. Oprah’s approach, widespread in today’s society, affirms self-definition and self-reliance but leaves people with no resources but their own selves—which for most of us, most of the time, are meager. Families, churches, neighborhoods, nations . . . these features of a well-grounded life are absent.

Addicts probably don’t read books outlining strategies of self-care; dissatisfied souls yearning to escape an ordinary life do. Celebrity culture feeds into discontent with what is common. It’s no accident that Oprah’s book is filled with the advice and commonplaces of celebrities, from Deepak Chopra, Ellen DeGeneres, Joe Biden, and Jon Bon Jovi to Cindy Crawford, Jay-Z, Stephen Colbert, Tim Storey, and Marianne Williamson. In this, she follows the original model, Smiles’s Self-Help, which cites notables from Shakespeare, Newton, and Bacon to Sir Walter Scott, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Disraeli, and Josiah Wedgwood.

The use of models, or exemplars, is at least as ancient as Plutarch’s Lives. In Oprah’s book, Storey and Williamson are “life coaches”; in a broad sense, all the celebrities in The Path Made Clear operate as life coaches. Your life is wonderful, but you don’t know it yet! Think about beautiful things, and they will come. Or as Tim Storey says, “You are a mighty person in the making. You are a miracle in motion. We’re not there yet. But we’re in motion.” I can’t wait to get there. Storey’s breezy, alliterative self-confidence brushes right past the fits and starts of everyday life. Or the affliction of ordinariness, which can’t be cured with sweet words. After all, most of us are clustered around the mean, never more than a standard deviation away from the commonplace.

At one level, Oprah and Storey offer little more than up-to-date versions of Norman Vincent Peale’s commendation of the power of positive thinking. But their techniques of affirmation also recall one of the giant figures of the nineteenth century: Walt Whitman, the greatest life coach of all. Whitman elevated ordinary people to the ranks of the extraordinary, in part by wrapping himself around the lives of others. He donated himself to what is common, and he drew into himself what is ordinary, portraying both as heroic acts of the democratic soul in which every American shares.

You can’t read Leaves of Grass without wondering which part of Walt’s persona is his and which part belongs to that vast forest of common life he draws into himself. What looks like sheer narcissism in the poet’s song of himself opens into the larger unfolding of life. Whitman is “the poet of comrades.” In “Song of Myself,” he announces, “I am of old and young, of the foolish as much as the wise”; “Through me many long dumb voices”; “I do not ask the wounded person how he feels, I myself become the wounded person.” In “Starting from Paumanok,” he writes, “I am the credulous man of qualities, ages, races, / I advance from the people in their own spirit, / Here is what sings unrestricted faith.” The I is never simply the poet’s voice; it is everyone else’s voice as well.

The word Whitman favored was “common,” not “ordinary”; “ordinary” never appears in Leaves of Grass. He sang in “Song of Myself,” “What is commonest, cheapest, nearest, easiest, is Me. . . . Of every hue and caste am I, of every rank and religion, / A farmer, mechanic, artist, gentleman, sailor, quaker, / Prisoner, fancy-man, rowdy, lawyer, physician, priest,” in “this the common air that bathes the globe.” He spoke of “slow-stepping feet, common features, common modes and

emanations.”

For all his talk of the common, Whitman magnified himself. He acquired a celebrity status of sorts by manipulating the celebrity culture of his time, as David Haven Blake has argued. He wrote anonymous favorable notices of the first edition of Leaves of Grass, flaunted a facsimile of his autograph in the book, and used staged photos of himself, such as one in which he gazes at a cardboard butterfly poised on his hand. Not above commercial exploitation of his notoriety, he endorsed a brand of cigars named after him. The readers to whom he spoke so intimately were woven into the fabric of his poems. They are the crowd, ordinary folks, made partners in the poet’s promotion of himself. In this way, Whitman was like the powerful politician who adopts a folksy demeanor. The effect is not to bend down but to raise up. Whitman is really saying to his readers that they are not ordinary. How can they be if he, too, is part of the crowd? “Just as you feel when you look on the river and sky, so I felt,” he writes in “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” And in “By Blue Ontario’s Shore,” he affirms, “We are the most beautiful to ourselves and in ourselves.” From the same poem: “Produce great Persons, the rest follows. . . . I am he who tauntingly compels men, women, nations, / Crying, Leap from your seats and contend for your lives!”

Whitman’s pep talk works like an elixir. He brings “good health,” strengthening the fiber of our being. It’s a form of self-advertising, to be sure, but his poetry goes beyond the promotion of self. By identifying so closely with ordinary folk, Whitman the “kosmos” suggests a blending of the I with the whole. His own extraordinariness is made visible through his affirmation of the ordinary lives of others, an affirmation available to anyone willing to embrace the democratic spirit. Through the technique of accumulation (itself an innovative use of the classic amplificatio), his enumerations of different persons, labors, things, and geographies become repeated affirmations of unity in variety, a modern prayer to a chain of being to which we all belong. Vermeer elaborated the customs and context of the lacemaker’s art. These are her ties to a shared world, a common world, and those ties are the substance of her beauty, allowing him to paint her as she draws us into the world she is making. Whitman’s arrangement of the universe in Leaves of Grass seeks something similar. He wants to sing of what is common, and in so doing elevate his readers to a shared condition of democratic fellowship. But all too often the poetic effect rests on Whitman himself, a surcharged personality that dilates and buoys us up while what we hold in common—our ordinary traditions, our varied customs, our differentiating manners—disappears in his grand embrace.

The equality that inspired Whitman is an ideal, not a variegated and inherited social reality, as was the case for Vermeer’s lacemaker. Whitman’s genius was to give that ideal an embodied poetic expression, drawing from the ordinary features of life around him. But what is sung in verse is not lived in life. Whitman anticipated the obsession with celebrity, the fetish of individualism, precisely through his gregarious hyping of the ordinary.

Confusing the ordinary with the extraordinary carries grave risk. “Song of Myself” begins, “I celebrate myself, and sing myself, / And what I assume you shall assume.” That is a remarkable presumption, perhaps unavoidable as part of the democratic proposition to which Whitman was devoted, which may be why individualism, the cult of celebrity, and a pervasive belief in greatness latent within everyone are very American. But Whitman’s is a presumption that assumes no liabilities, no enduring debts, no nagging guilt, no incurable defects. In this respect, Whitman falsifies reality, for these centripetal forces always and everywhere are part of what is common. Life coaches or self-help gurus airbrush the ordinary in the same way. They promise that your ordinary life is always already something great; the bad stuff is just the alien husk of the real me, waiting to be cast aside. All you need to do is be yourself!

Turning life into an endless selfie was not Whitman’s aim. Elevating the vigor of a common life was: “Leap from your seats and contend for your lives!” Indeed we should. But as we contend, we do well to contemplate Vermeer’s lacemaker. We contend best not in spasms of self-affirmation or even self-help. We need strong roots in order to leap with consequence. The wearying tasks of doing one’s craft with care and dignity, accepting long apprenticeship as a condition for excellence, and harkening to the divine for help and counsel—these are the foundations of the lacemaker’s art. In Vermeer’s painting, the lacemaker shines within a world of custom, convention, and discipline. What we see is not an aura or a “destiny.” Hers is a life that is part of a way of life. Therein lies the beauty, the window onto the uncommon and extraordinary.

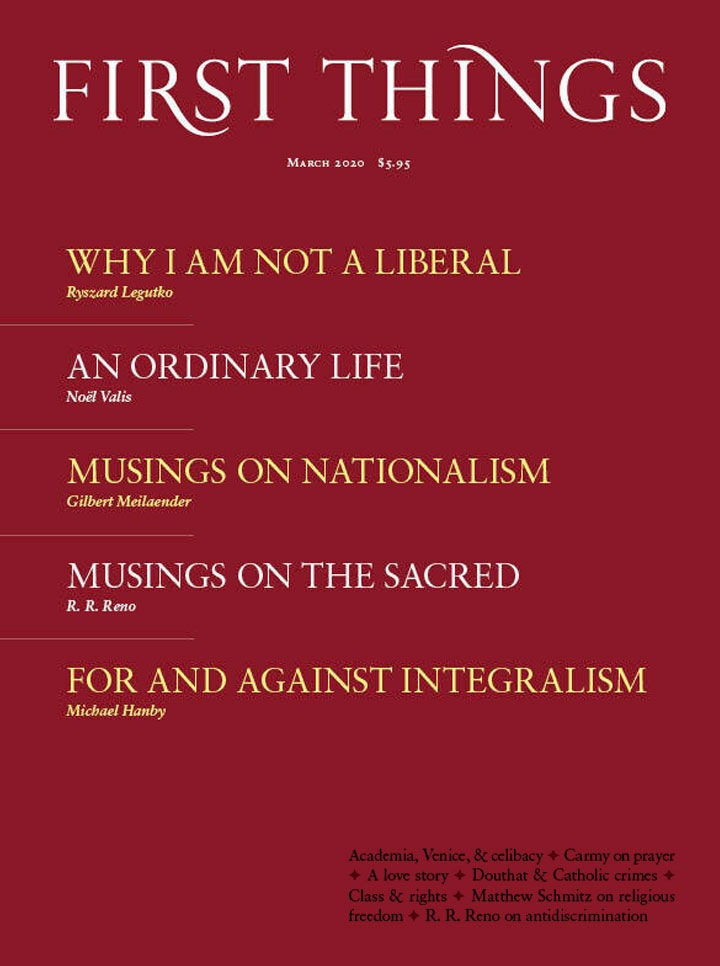

Noël Valis is professor of Spanish at Yale University.

Bladee’s Redemptive Rap

Georg Friedrich Philipp von Hardenberg, better known by his pen name Novalis, died at the age of…

Postliberalism and Theology

After my musings about postliberalism went to the press last month (“What Does “Postliberalism” Mean?”, January 2026),…

Nuns Don’t Want to Be Priests

Sixty-four percent of American Catholics say the Church should allow women to be ordained as priests, according…