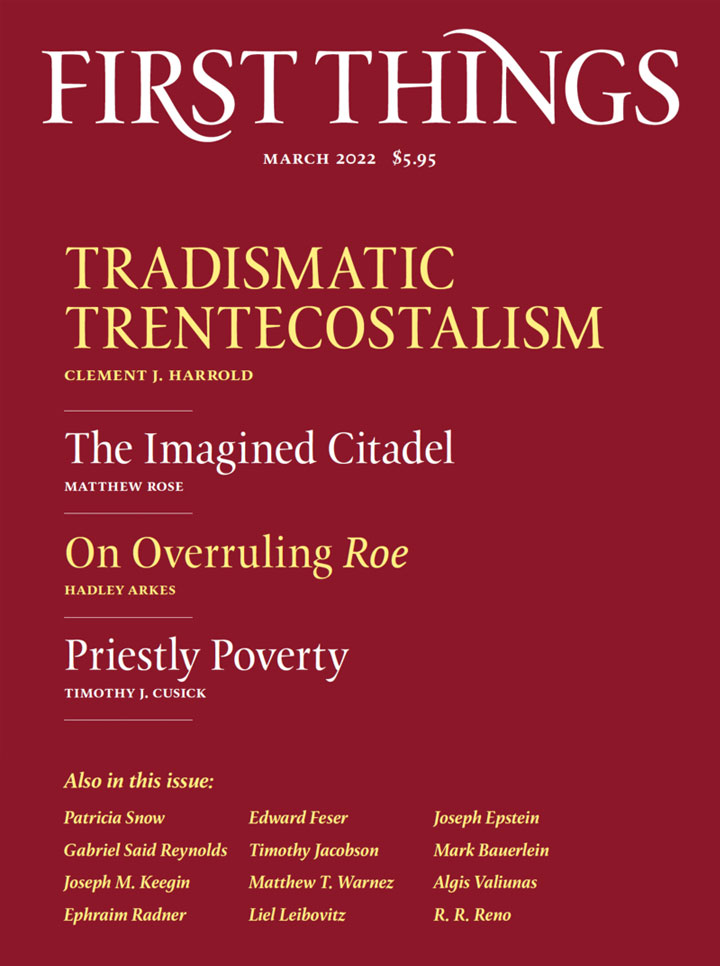

Steubenville, Ohio, home to Franciscan University, is a small city on the banks of the Ohio River linking the Buckeye State with Pennsylvania and West Virginia. Like much of the Rust Belt, Steubenville has seen better days. But coinciding with economic downturn has been a spiritual renewal that offers hope to the American Church: a unique blend of the “traditional” and “charismatic” liturgical-spiritual elements that in many other places are pitted against each other. It is a synthesis that appeals to head and heart alike, suggesting what the Church might become in the twenty-first century.

Franciscan University gave me my first exposure to the American Church after an adolescence spent in the spiritual wasteland that is modern-day England. Steubenville became for me a site of spiritual flourishing, for it was here that I first experienced a mature and meaningful relationship with Jesus Christ. It was here also, at the campus chapel, that I first heard “How Great Thou Art” played on a guitar, and first witnessed the contradiction of a female worshipper wearing gym shorts and a mantilla. And yet the chapel in which these encounters took place was always full. And so, despite occasional incongruities, I am convinced that the “tradismatic” synthesis emerging in Steubenville is worthy of emulation.

Steubenville’s charismatic character dates back decades, to the early years of the presidency of Michael Scanlan, T.O.R. Beginning in the mid-1970s, Fr. Mike sought to make Franciscan a leader in the fledgling Catholic charismatic renewal movement. As he explains in his autobiography, “The charismatic renewal embodied the kind of dynamic faith that I thought should shape the college life, a faith marked by free praise of the Lord, spiritual gifts, commitment to one another’s welfare, and a life of prayer.” Fr. Mike viewed this renewal as an antidote to the cultural chaos of the 1970s. At one time, he faced calls from students and staff for the ending of Sunday morning Masses. In response, he announced that the Sunday Masses would be lengthened to allow more time for praise music.

Franciscan continues to be a place where souls with a charismatic leaning find a home. From the pulpit and in campus ministry, a radical openness to the Holy Spirit is emphasized, as are the healing power of grace, the power of testimony, the necessity of praise, and the importance of joy in the Christian life. At the monthly Festivals of Praise, which draw a third or more of the student body, ministry teams pray over individuals seeking spiritual or physical healing. This practice is always regarded as supplementary to—never a substitute for—the Sacrament of Confession, which is offered five times per week on campus. I can attest that my years at Franciscan changed my life, precisely thanks to the university’s commitment to joyful liturgy, confident prayer, and authentic Christian community.

In the past two decades, however, another spiritual-liturgical recovery has taken place within the Western Church, propelled in large part by the young. Often called “traditionalist,” it can be described as a desire to return ad fontes—“to the sources”—and reclaim the full sacramental and ecclesial patrimony that has too often been denied us. In a move that may appear surprising, the Steubenville community has largely welcomed this recovery. An increasingly popular approach, especially among undergraduates, has been to adopt and synthesize the best parts of both charismatic and traditional spiritualities. Hence an embrace of the emotions in prayer need not slide into emotivism. Effective catechetics need not be extolled at the expense of sound catechesis. Pedagogy and mystagogy can and should work together.

The spiritual and liturgical life at Franciscan University responds to the younger Church’s desire for a Catholicism that embraces many of the traditions and rituals of Catholics who lived before the 1960s, without rejecting the good to be found in the charismatic movement. During my time serving on student government, for example, we conducted polling that showed that more than 90 percent of students at Franciscan supported the putatively “trad” measure of introducing patens in the distribution of Holy Communion—an indication that old labels might need revision. A few years ago, the T.O.R. Friars undertook a major work of beautification in the campus chapel, which included returning the tabernacle to the center of the sanctuary. As the director of chapel ministries, Shawn Roberson, T.O.R., explained to me: “Franciscan is, at its heart, a Christ-centered university and as such it strives to have good and vibrant liturgical celebrations whether that is in the Novus Ordo, Traditional Latin Mass, or the Byzantine Rite. Our fundamental witness is our active participation in the liturgical life of the Church.”

These days, many students attend the more charismatic Masses offered on campus, where the music is contemporary, the priest faces the people, and numerous students receive Holy Communion kneeling and on the tongue. Likewise, many students receive the Sacraments at St. Peter’s Church downtown, where one can experience the Novus Ordo Mass celebrated ad orientem. Still others choose to attend the Latin Mass or the Divine Liturgy. In every case, students are seeking to appreciate the beauty in different liturgical expressions while recognizing the importance of reverence and rubric. As graduate student Maria Therese remarked: “Franciscan exemplifies the reality that tradition and charism are not opposed to each other but are fundamental pillars which build up the Church.” For my part, I am a student of the Latin language and see great beauty in the ancient rite, though I typically attend the Novus Ordo and routinely listen to praise and worship music, much of it written by Evangelical Protestants.

In a Church where 70 percent of the faithful no longer believe in the Real Presence, legitimate differences between charismatics and “trads” pale in comparison to the differences that separate orthodoxy from heterodoxy. Faithful Catholics of all stripes increasingly find themselves allies against the common foe of a corrupt Church and a post-Christian world. In the words of Jacob, a recent graduate now studying for the priesthood, “it is primarily the youth who are working through the false dichotomy of charismatic and traditional divisions in the Church.” The “tradismatic” spirituality found within the student body of Franciscan is a vibrant synthesis, one that modern Catholicism ought to prize.

Yet this synthesisis unwelcome in some quarters. Some in the episcopacy view the movement toward greater reverence and tradition with alarm and disdain. Pope Francis’s recent motu proprio Traditionis Custodes, which attempts to restrict severely the celebration of the Latin Mass, betrays this sentiment. Nostalgic for their vision of the 1970s Church, the Holy Father’s advisors cannot seem to understand either the charismatic zeal or the love of tradition that characterize many of today’s Catholic youth.

A case in point arose for me a few years ago when I attended a call-to-action meeting of liberal Catholics in Bristol, England. Having shared during the open floor session my desire as a young Catholic for a return to a radical faith, I was confronted by an elderly gentleman as soon as the meeting was over. He could not understand why I would support an institutional Church that “treats us like children,” with all its rules and moral codes. I cited Matthew 18:3: “Truly, I say to you, unless you turn and become like children, you will never enter the kingdom of heaven.” He walked away without another word.

Traditionis Custodes bespeaks a Catholicism stuck in the past. On the whole, Catholics my age are not interested in ideology or party politics. We feel wounded by a world that seeks our spiritual ruin and betrayed by a Church hierarchy that often goes along with the world. We cannot understand how any bishop or pope could ignore the devastating effects of the liturgical iconoclasm wreaked in the 1970s Church, and we feel wrongly deprived of the liturgical and cultural patrimony that our forefathers in faith laid down their lives to defend. Yet we have no schismatic impulse. We find solace in the unity the Catholic Church offers as an antidote to the turmoil of the world: a unity neither homogenous nor static, but incorporating, and enriched by, legitimate diversity.

When I read St. Paul, I detect some of the spiritual practices charismatics highlight and trads at times downplay. I find no evidence that these practices were intended to be limited to the early Church. The joy, the emphasis on healing, the love of Sacred Scripture, the confidence in the power of grace—all of these are laudable. Charismatics internalize the idea that there is something in our faith worth shouting about, and their feeling is that if King David can dance in the presence of God, then so can we. I find it impossible, moreover, to fault some of the liturgical practices of, say, the African churches. The custom in Uganda, for instance, of the whole congregation’s breaking into applause at the moment of the Consecration seems to me a witness of Eucharistic coherence par excellence. This is not to excuse liturgical abuses or to offer other cultural customs as a prescription for the West, but only to recognize that it takes all sorts to make a Church.

By the same token, among traditionalists one detects a consciousness of essential elements the charismatics at times neglect. The importance of a daily examen, the necessity of striving for habitual virtue, awareness of the poisonous reality of sin—trads appreciate and emphasize these spiritual disciplines and combine them with worship that highlights the centrality of Christ’s sacrifice. Trads get what the Psalmist means when he invites us to be still and know who God is. They favor a counter-worldly promulgation of beauty that lifts the mind to heaven. As a counterweight to occasional liturgical experimentalism on the part of charismatics, they call to mind the injunction of the Apostle that we should “test all things” (1 Thess. 5:21). They rightly recognize, too, the damaging effects the eradication of the Latin language has had in dislocating us from our cultural and religious birthright. (Having attended Mass in ten or more tongues, I am convinced of the unifying and progressive nature of a common liturgical language, while still conceding the pastoral efficacy of the vernacular.)

One of my favorite lines from John Henry Newman comes in his Development of Christian Doctrine, where he speaks of just the kind of Catholic synthesis I have attempted to outline here: “One aspect of Revelation must not be allowed to exclude or to obscure another; and Christianity is dogmatical, devotional, practical all at once; it is esoteric and exoteric; it is indulgent and strict; it is light and dark; it is love, and it is fear.” Catholic Christianity surely is all these things and more. It is faith and works, nature and grace, virtue and Spirit, charismatic gifts and liturgical traditions, body and soul, head and heart. Tradismatics, Tradicals, Trentecostals, Born Again Catholics: These are what the Church of tomorrow will be made up of, even as we continue to look forward to that day when in the manifold unity of the Blessed Trinity—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit (or Ghost)—God will be all in all.

Uncovering the Real Melania

Melania, Brett Ratner’s documentary following the first lady of 2017–2020 around as she gets ready to become…

The Evangelical Elite Gap (ft. Aaron Renn)

In this episode, Aaron Renn joins R. R. Reno on The Editor’s Desk to talk about his…

Don Lemon Gets the First Amendment Wrong

Don Lemon was arrested last week and charged with conspiracy against religious freedom. On January 18, an…