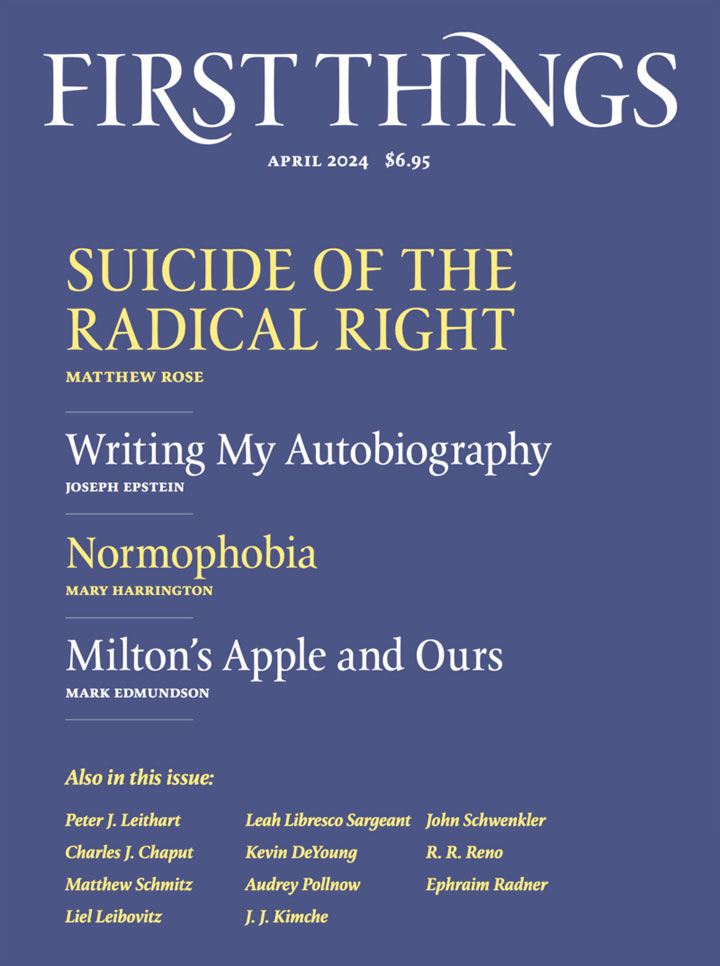

Why did Eve bite the apple? Milton puts this question at the center of Paradise Lost, the greatest long poem in English. Why did Eve listen to Satan, pluck the apple from the tree, and take a bite? This temptation bears on us now. Satan always hides in plain sight. So it’s no surprise that there on the laptop, courtesy of Steve Jobs, you see an image of the apple with the fatal bite taken. It’s a brilliant piece of corporate poetry. Open the computer, Satan says, log on, engage. Bite the apple. Become as gods. In Milton’s story about a garden, an apple, and the quest for godlike knowledge, we can see a reflection of our own encounter with computers and artificial intelligence—and the way we might fall, or navigate it virtuously.

Milton tells us that on a certain day in heaven, prelapsarian Satan, one of the highest-ranking angels, flies into a rage against God. God’s crime? He has revealed to the angels—Thrones, Dominations, Princedoms, Virtues, and Powers—that they are now subordinate to a figure God calls the Son. The Son is the ruler of all the heavenly hosts. He is also, God proclaims, their creator. The Son made them all, and is eternal, like the Father, though up until this day, the angels have known nothing of him.

Satan’s rage stirs a mighty headache, until from out of his forehead bursts a terrifyingly seductive figure. Later she recalls her birth:

Out of thy head I sprung; amazement seized

All th’host of Heav’n; back they recoiled afraid

At first and call’d me Sin, and for a sign

Portentous held me. (II, 758–61)

Here is the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus with a twist. Out of Satan’s head comes not wisdom but gorgeous horror.

Immediately Satan falls in love with Sin. She is his own reflection, and she relishes the fact that she is irresistible:

Thyself in me thy perfect image viewing

Becam’st enamored, and such joy thou took’st

With me in secret, that my womb conceived

A growing burden. (II, 764–67)

Satan impregnates his self-image, who will give birth to their monstrous child, Death.

Satan’s fall prefigures that of the original man and woman and sets the pattern for Milton’s reflections on why Adam and Eve eat the apple—and why we too, have bitten ours. It begins with self-love, with Narcissus, though there’s more to it than that.

Eve is disposed to self-love from the start. When we first meet her, she is recounting the tale of her origins, looking into a pool, and falling in love with her “smooth wat’ry image.” The passage is charming:

A shape within the wat’ry gleam appeared

Bending to look on me, I started back,

It started back, but pleased I soon returned,

Pleased it returned as soon with answering looks

Of sympathy and love. (IV, 461–65)

God’s voice intervenes to let Eve know that the image in the pool is a reflection of herself, not another being she can possess. He offers her substitutes: He will lead her to Adam; she’ll bear children, “multitudes like thyself.” But the allure of the image persists. Eve gets her first look at Adam, standing in front of a platan tree, and finds him “fair indeed and tall,” but “less winning soft, less amiably mild, than that smooth wat’ry image.” Eve turns around to find the image again, and Adam pursues her. “Thy gentle hand seized mine,” Eve says. How alluring must that glorious reflection in the pool be for Eve to run from Adam and defy the voice of God?

Hiding nearby, Satan overhears it all. He knows Eve to be a kindred spirit. She too swoons before her own image. When the temptation begins, he will use what he’s learned, praise her beauty and promise her not “multitudes like thyself,” but multitudes of admirers. Now she has only one man to gaze on her with delight. What is one when a whole universe longs to see her in the godly state she’ll attain after she eats the apple?

Milton’s moral is simple: When you love yourself and embrace yourself and yourself only, you stop loving others. Milton’s image of paradise is a garden where a certain kind of love presides. Adam is responsible to and for Eve and she for him. They are both responsible to the animals, whom they love, and to the verdant green earth. They are gardeners. Every day, they tend the plants and the soil, prune the trees, trim the grasses, harvest fruit, and, after prayerful thanks, eat it. They take care of what is below them in their world and they look to what is above with wonder and gratitude. When the sociable angel Raphael comes to visit, Adam questions him about the workings of the universe.

Adam and Eve are vegetarians. Before the Fall, it is inconceivable to them to harm any miraculous creatures God made to share the garden. When Raphael sits, they serve him fruits, giving rise to the only joke the narrator makes in the poem: “no fear lest dinner cool.”

Self-love threatens this earthly order, just as Satan’s self-love does the order of heaven. Self-love takes your focus away from what is above you and what is below. You forget about the welfare of inferiors and the gratitude you owe superiors. Harmony, coherence, and belonging begin to fail. Satan’s self-love leads to rebellion and makes him an apostate. He takes a third of the angels with him, destroying the joyful harmony of heaven. Before Satan’s rebellion, the angels gather in mystical song and dance that reaffirm creation and enhance their connection to one another and to God. Satan and his minions replace the ceremonies of heavenly innocence with war.

There’s something else. Satan doesn’t tempt Eve only with the narcissistic dream. He offers an expansion of consciousness. He tells her what the fruit has done for him, and leaves her to imagine what it will do for her:

Thenceforth to speculations high or deep

I turned my thoughts and with capacious mind

Considered all things visible in heav’n,

Or Earth, or middle. (IX, 602–5)

Satan claims that eating the fruit has expanded his mind: He sees more; he knows more. And so it shall be for Eve. Satan tells her that the fruit—the apple—gives him power to discern “things in their causes” and “to trace the ways of highest agents, deemed however wise.” The last phrase—“deemed however wise”—is a dig at God and the tutelary angel Raphael, who comes to instruct Adam and Eve. There is more in heaven and earth than is dreamt of in their divine philosophy. There is Satanic wisdom to be had.

The demonic science comes in two forms in the poem. Despite Satan’s implied promise that the fruit will deliver metaphysical “speculations high or deep,” both are material and pragmatic. The first is Pandemonium. Pandemonium is the city that the devils under Satan’s charge build in hell, after the Son has driven them down. The city is stunning, ornate, intricate, amazing, and it is the seat of evil. There, the devils consort and plan ruin for mankind. In Pandemonium, you’ll find Moloch, Belial, and Satan’s admirer, Beelzebub. They have time, proximity to one another, and devilish luxury to compound their plots. These angels, cast by God into hell, will in time become the false gods of the wayward people of Israel. Men will follow the demons’ example and also become builders of cities, and “with impious hands / Rifle . . . the bowels of their mother Earth / For treasures better hid” (I, 686–98).

The other Satanic wisdom emerges on the second day of the war in heaven, when the rebel angels attack God’s loyalists. On the first day, God’s angels create havoc among the rebel ranks. The archangel Michael, greatest warrior in heaven, decimates the files of demons. Though the devils cannot perish, made as they are from immortal stuff, they endure bitter pain.

On the second day the evil spirits rally. They face their foe not with swords and shields but with Satanic engines, cannons that, Satan says,

with touch of fire

Dilated and infuriate shall send forth

From far with thund’ring noise among our foes

Such implements of mischief as shall dash

To pieces, and o’erwhelm whatever stands

Adverse. (VI, 485–90)

And the Satanic engines do succeed in blowing apart the ranks of the loyal angels. God’s angels counterattack by seizing enormous hills, throwing them on their foes, and crushing many. Still, the devilish engines do their work: They manage to rout God’s legions.

Notice that it’s nature—grass and soil—that the heavenly hosts call to their aid. Paradise is not to be found in a city. Paradise is a garden, green and beautiful, and it requires human beings to tend it with care. In the garden we attend to order. We look up in gratitude to our superiors and look down, solicitously and kindly, at lesser beings. We cherish the land: We’re environmentalists of a pious kind. We use tools that till the earth, gently, but we do not construct tools to draw from the earth more than it readily gives. We conserve the world as it comes to us from our creator. Cities are suspect: They can devolve into Pandemonium. And technology is yet more so: In Milton, technology gives you weapons of war.

Milton’s dialectic is clear. God commends a life that is pastoral and pacific. God blesses gardening of a gentle, non-mechanized sort. He affirms leisure. Adam and Eve spend much of their time enjoying the garden and praising it. Their labor is light, almost a form of recreation. They pray frequently, thanking God for what they have. It’s a vessel for their grateful imaginations. Prayer is the poetry of Eden.

Satan represents a life that is urban. That’s where energy lies, where beings collect and collaborate to create new possibilities. The devils in hell seem less inclined to leisure than to plotting and scheming. Their work is never done. Satan is the god of technology: His dark engines show you as much. His spirit infuses the drive to create one transforming device after another.

In Milton’s poem (and in the present), Satan is the bringer of the apple. He invites us to take the city as the source of human flourishing and to adopt the faith of technology. His vision of what is best for humans is dangerous, but it is anything but empty.

The great poem lays out the crucial choices that we must navigate. Call it the dialectic of the city and the garden. We have embraced the machine, the city, technology, the computer. We have downgraded the garden: spontaneous art, leisure, gentle connections with others, love for plants and animals. Of course, technology has been and can be a blessing. But it’s a mistake to develop a culture that idolizes the machine. Milton gives us the terms with which to challenge that false religion. The ethos of the garden should always interrogate the ethos of the machine.

When Adam questions Raphael about the workings of the cosmos, the genial angel answers his questions fully and with pleasure. At a certain point, though, Rafael lets Adam know that it is not in his interest to push too far. The ethos of the garden sets limits on knowledge. For unfettered knowledge gives us Pandemonium, the Satanic engines. The apple can destroy life. We shouldn’t take another bite without deep reflection.

How are we to begin?

Milton leaves us a clue. The Fall of mankind is based on the quest for forbidden knowledge, yes. But it has its roots in the malady of Narcissus: Satan and Eve both fall to self-love. When we encounter the choice that Satan provokes—the garden or the machine?—we need to begin by asking a simple question: Does this innovation serve the self-love of its beneficiaries at the expense of community and harmony? Does it function at the cost of the green world, the earth, our commitment to gratitude, kindness to others, and praise of what Coleridge called “the one Life within us and abroad”? Does this particular machine do harm to the garden? Sometimes the garden may need to be reordered and replotted, but never radically, never in its entirety. Always be suspicious of what threatens the green world and our contact with it.

Can robots—they are on the horizon—be used in ways that don’t utterly outrage the garden ethos? Can having a slave, even a mechanical one, fail to corrupt us and to degrade our connections with others? Will the mechanical man or woman diminish love between two humans, the garden virtue that Adam and Eve cherish most? (“Sex robots are coming,” read a billboard I recently encountered.) Entirely artificial means of reproduction are also coming. Where will wonder and gratitude go in a world where we can almost reproduce the miracle of God’s sixth day of creation? Before we bite any apple, and bite it again, we need to stand before the jury of the garden and its blessed way of life.

Garden values resist idolatry. With the creation of AI we can believe that we have become as gods. After all, we have created new and astounding forms of being. Why not worship ourselves for doing so? Why do we need to look down at Nature and honor her? Isn’t the greatest imperative to exploit the material world to fuel technological progress? And what’s the point of looking up at God? We can worship ourselves, the way that Satan does, and that Eve is brought to do.

You say you don’t believe in God, and that there’s no need to offer prayers of thanks? If you cannot recognize and thank God, I suggest that you observe the Mystery that has brought this glorious earth and human life into being. Existence is a wonder—the world shines with more glory than any tools or toys that we can conceive. The Buddhists say that they give thanks, even if there is no one or nothing to thank. Walt Whitman says that he sees God in every human face and in the face of nature, though he has no interest in knowing God’s essence at all. The Buddhist monks and the great poet of democracy are of the Edenic party, a capacious one that welcomes those who accept responsibility and express gratitude.

Artificial intelligence promises to do our work for us, and that is an enticing possibility. We can have more leisure, do what we like. We can be free. A forward-looking young guy went on Twitter to envision the prospect: “AI is going to take away all of our jobs and render us useless. And I, for one am stoked. I hate jobs. I had a job once, and everyone there talked in weird voices. AI is going to 86 all that.”

The Bro says that in the near future everyone should be “breaded” (great word) to the tune of about ten thousand dollars a month. Computer technology can make it happen. Why not go ahead?

The Garden generates a different view. God could easily have created an Eden in which people did not have to work, leisure all the time. But God did not. Adam and Eve prune and tend and harvest. Life without work is not worth living, at least according to the garden view. Not overwork, though, which is a problem, too. People must know when to stop or they’ll spend their lives tuning the robots and becoming ever more robotic in the process. The garden says no. Adam and Eve spend a large quotient of their time enjoying and praising the bounty that God has given them.

Will you let ChatGPT do your writing and thinking for you?

When we arrange words into coherent and sometimes revelatory speech and writing, we create our own vision of the world. We put our stamp on reality, a venture of interpretation that puts a stamp on us. In the Garden the speech most treasured is prayer. Adam and Eve talk to God and create a grateful vision of their own lives there. Religions are full of rote prayer, and there may be a place for that, but in the Garden prayer is spontaneous articulation.

Computer speech, scripted by AI, runs in the opposite direction. It’s a medium for conformity. It causes us to say what has been said before in the most literal way. We are inhabited—we might even say possessed—by the machine. What is fresh and bright and new in us languishes and in time may die. If machines speak through us, we become machines. Language is what gives us freedom and individual presence: It is both collective (all humanity has contributed to it) and individual (when I speak, I render myself). Those who speak with zest and invention enjoy the freedom of Shakespeare and Milton. In the garden we gain the gift of poetry.

Milton and the Bible tell us that the apple brought us the knowledge of good and evil. I’m not sure we understand that outcome in the right way. It’s not that Adam and Eve know what’s right and what’s wrong as soon as they bite the apple. They don’t become instant moral arbiters. By my reading, Milton suggests that, from the first bite of the apple, Adam and Eve will be compelled to pursue knowledge of good and evil. After Satan (the city, the machine), life presents itself as a series of crucial decisions, which makes life itself a problem in which distinguishing between good and evil is paramount. Milton does not answer our questions directly. He does not tell us how to think and what to do about the question of AI. What he does do is establish the terms for debates about this or any other issue: garden and city, pastoral and technological. Once we have clarity about these terms, we can begin thinking. Right now, we are lurching forward, not thinking.

I believe that young people will soon revolt against Satan’s ethos. They’ll unplug their apples, go back to the land, worship nature, grow their own food, and turn off Spotify so that they can make their own music, sing their own songs. And I’ll be cheering them on.

There are signs that a taste for garden life is returning. A course at the University of Pennsylvania called “Living Deliberately” requires students to unplug their devices, dress more simply, and talk sparingly if at all over the period of a month. Students are flocking to it: Back to the garden! Get thee behind me, Satan!

But let’s not make a mistake. In one of the most beautiful hymns to the sixties, “Woodstock,” Joni Mitchell sings about going back to Eden. She wants a complete transformation of the world: the city world, the techno world. Here is the garden, the country, Max Yasgur’s farm where the Woodstock Rock Festival took place—Three Days of Peace and Music. Joni crystallizes the vision in a wonderful image: “I dreamed I saw the bombers / Riding shotgun in the sky / And they were turning into butterflies above our nation.” The garden will overcome Satan! Total victory, butterflies and grass over the grinding war machine! It’s a sweet dream: “We are stardust / We are golden . . . / Caught in the devil’s bargain / And we’ve got to get ourselves / Back to the garden.”

But no. Not quite right, lovely as it is. We’re never going to get ourselves back to the garden, and we’d be fools to live entirely without technology. We must never forget the garden, though. Garden values must be on hand to consider and to judge every innovation that comes before us.

Joni’s right, we are in the midst of an exchange with Satan—with technology, with AI, with the machine. You can never fully evade him. Notice how he slips his nose into the song, when Joni finds herself celebrating the fact that she feels just like “a cog in something turning.” That’s not Garden language at all; it’s the machine talking, beckoning. We need to do some negotiating. Satan, apple ever in hand, drives a hard bargain, but in this exchange, we are not without resources. We have faith, the tender aspects of the human heart, mutual love, the values of the garden, and a 350-year-old poem on our side.