Liberals and conservatives disagree less about principles than we often imagine. (It’s common for intellectually inclined, theory-informed people to interpret disagreements about policy as matters of principle.) For example, aside from full-bore revolutionaries, everyone endorses the rule of law, even as we sometimes violate that principle in the heat of political battle. I regard the prosecutions of Trump as political in nature, something liberals tolerate (or refuse to acknowledge) because they think the stakes are so high that principle must be relaxed. They convince themselves that bending the rule of law is necessary to prevent a demagogue from gaining power and flouting that same rule of law. The same line of reasoning justifies social media censorship and other illiberal collusions of government and corporate power to suppress speech.

This inconsistency among liberals illustrates my point: Our judgments about political and social realities are often more decisive than our principles. If Trump in fact represents a threat to our constitutional system, if he commands a proto-fascist army of ardent supporters, then dire countermeasures are justified, even extra-constitutional ones.

I don’t share the liberal establishment’s assessment of Trump, but I don’t want to litigate the immediate issue. My disagreement goes much deeper than any dispute over Trump’s rhetoric, personality, and role in American politics. As I’ve talked with my liberal friends, I’ve come to see that we have fundamentally different assessments of the central problems facing our country. They fear a closed-minded hostility to the “other.” I worry about the disintegration of crucial institutions and anchoring authorities.

Liberals think our society is too homogeneous, judgmental, hidebound, and restrictive. To some extent, this judgment is inherent to the progressive mind. Progressives seek to be open to the future, which they believe can be better and brighter—provided we’re willing to free ourselves from present constraints and embrace new possibilities.

The unique circumstances of the twentieth century encouraged this attitude. After World War II, liberals interpreted fascism as arising from a “closed-minded” mentality. Erich Fromm’s widely read book, Escape from Freedom, was a psychological version of this interpretation. A frightened, disoriented populace turns to authoritarian leaders because people fear the uncertainties and responsibilities of modern freedom. Another influential book, The Authoritarian Personality by Theodor Adorno and a team of social scientists, described traditional views of parental authority and sexual morality as proto-fascist. On this view, conservative sensibilities became suspect. They were symptoms of psychological disorder and harbingers of totalitarianism.

Few Baby Boomers have read these books. But having grown up during a period that was uniquely homogeneous, they were sympathetic to the main thrust of these and similar assessments of the dangers facing the West. After the war, the American middle class expanded dramatically. Society was governed by a largely traditional morality that prized being “normal.” In the 1950s, social scientists such as David Reisman, author of The Lonely Crowd, worried about the pervasive conformity of that era.

The 1960s brought many changes. The civil rights movement challenged bourgeois complacency. The sexual revolution took hold. Yet even amidst cultural uproar, marked by riots and anti-war protests, the homogeneity was palpable. Everyone watched the same TV shows. The then-young Baby Boomers thrilled to top-40 hits. Moreover, the decades after World War II were a time of extraordinary demographic stability. Aside from wartime refugees, immigration was minimal. By 1970, the percent of non-native born residents in the United States was at a historic low of less than 5 percent. (In 1890, that population had been nearly 15 percent; today it is reaching that level again.)

These factors, ideological, cultural, and demographic, fueled a consensus in favor of openness: the open-society consensus. It took unity and stability for granted and focused on the failures, injustices, and dangers of an overly consolidated society. To this day, being liberal means adopting the open-society consensus.

Consider the sixty-year-old Ivy League graduate and corporate lawyer. He is by no means radical. But he’s troubled by Trump’s harsh talk about deporting those who are here illegally, and he places a sign in his front yard: “In this house we believe . . .” He regrets some of the excesses of Black Lives Matter, but endorses the view that racism remains a major social evil. He’d rather not think about drag queens, transgender surgeries, and the chaos at the border, but if pressed, he’ll assert that we should reduce social stigma and make our society more inclusive. He believes that diversity enriches and strengthens the body politic.

I’m baffled by these sentiments, not because they are wicked, but because they are so disconnected from present realities. I look at America in 2024 and see a globalized and financialized economy that has eroded the foundations of middle-class prosperity. We’ve witnessed the striking decline of marriage and the near complete acceptance of all sexual practices. (Will the New Yorker ever tire of running articles about “throuples” and other deviant practices?) The old, censorious morality no longer exists, much less dominates. Charles Murray’s 2012 book, Coming Apart, documents the nearly complete secession of society’s winners from those who have been abandoned and damaged by the economic and cultural revolutions of recent decades. Demographic change—collapsing birthrates combined with high levels of immigration—is accelerating. Our body politic is increasingly fragmented, sometimes to the point of open hostility.

In a word, our society is threatened with disintegration. In the face of this peril, the regnant liberal consensus is worse than irrelevant; it’s part of the problem. Take as an example the southern border. Polling indicates that voters overwhelmingly favor stopping the influx of migrants. Yet the Biden administration does nothing, because liberal elites are beholden to the open-society consensus. Or consider the sad fact that children born to mothers without a college degree are likely to have no fathers in their homes. The response of liberal elites? Make Pride Month the nation’s most sacred celebration. Huge numbers are dying of drug overdoses—and liberal elites legalize marijuana.

There’s an academic fashion called “queer theory.” Unlike older efforts to secure gay rights, queer theory does not argue for the acceptance of homosexuality as normal. On the contrary, it opposes the notion that anything should be normative. “Queering” society means demolishing social authority, deconsolidating and disintegrating institutions that impose standards and censure deviance. This ambition is extreme, to be sure. University presidents, trustees, and other elites don’t embrace it. But the imperative of radical deconsolidation and disintegration makes sense within the open-society consensus, which is why universities hire and promote faculty who advance queer theory, just as they sponsor colloquia on critical race theory, programs of postcolonial studies, and other instruments of disintegration.

In Return of the Strong Gods, I argue that the open-society consensus has become a flesh-eating monster. We are living in a deconsolidated and disintegrated world, one that lacks the strong loves and loyalties that anchor personal and collective life. We need a new consensus that recognizes that fascism, middle-class complacency, racism, and other dangers of an over-consolidated society were our grandfathers’ problems. Our challenges are quite different. They can be summed up as the dangers of drowning in a liquid world.

We’re seeing the first signs of change. Both political parties have strong voices urging a pivot away from globalization and toward re-industrialization. This shift in economic policy gives priority to reconsolidation. Both candidates for president have proposed significant subsidies for newborn children—another sign of awareness that we need to buttress the fundamental institution of society, the family, rather than celebrating an infinite variety of “lifestyle choices.” Some are calling for a chastened foreign policy, another sign of the turn toward reconsolidation.

And we can observe a parallel spiritual trend, one that emphasizes God’s authority. Yes, we’re called to sanctify the world, but many are aware that we first must re-sanctify the church. We can’t “go to the peripheries,” as Pope Francis urges, unless the center holds.

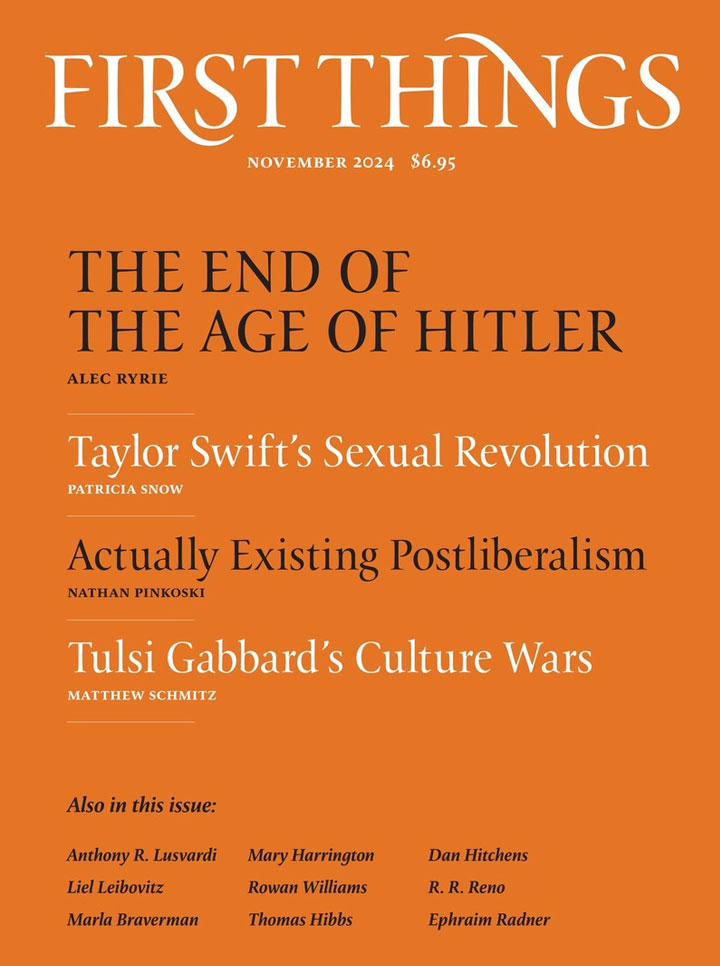

I’m convinced that a new consensus will take hold in the twenty-first century. (Alec Ryrie suggests something similar in “The End of the Age of Hitler” in this issue.) At some point, perhaps soon, responsible leaders will recognize that we need to do the opposite of “queering”; we need to restore the stable anchors of spiritual, moral, and political life. When that change comes, the application of principles—left, right, and center—will change as well.

Richard John Neuhaus

Does the founder of First Things matter in 2024? It’s a question that Aaron Renn asks in his Substack newsletter. He was prompted by James Davison Hunter’s recent book, Democracy and Solidarity. Hunter pairs John Dewey and Reinhold Niebuhr as exemplary figures in mid-twentieth-century America. A prolific writer, Dewey was an influential voice for progressivism in politics and education. Arguably the most widely read American Protestant theologian of his generation, Reinhold Niebuhr helped many see the dangers of liberalism’s naive optimism.

Hunter also pairs Richard Rorty with Richard John Neuhaus. Both exercised significant influence in the later decades of the twentieth century and at the beginning of this one. Rorty, like Dewey, was a spokesman for pragmatism in philosophy and progressivism in politics. As readers of First Things know, Neuhaus endorsed orthodoxy in religion, truth in morality, and, like Niebuhr, a chastened liberalism in politics—the outlook that came to be known as neoconservatism.

Renn observes that in both instances the progressive paladin enjoys lasting notoriety, whereas the figure on the right has faded from public view. I think he is mistaken.

I don’t wish to dispute Dewey’s influence. More than any other figure, he steered American liberalism toward a cocksure progressivism that pretends to be nothing more than common sense applied to changing social circumstances. His theories of learning and pedagogy have helped produce today’s dysfunctional educational culture. All true, but my point is this: In the last fifty years, few have read John Dewey, except when assigned to do so in an advanced college seminar on the history of American philosophy or educational theory. There are good reasons why Dewey’s work is neglected. I recently read his 1919 book, Reconstruction in Philosophy. It’s a treasure trove of progressive rhetoric masquerading as argument, rhetoric still very much with us today. But my reading of the book was the exception. Few people interested in contemporary philosophy, politics, or religion would pick up that volume. I’m willing to bet that Reconstruction in Philosophy has not been read by anyone who earned a Ph.D. in philosophy in the last forty years, beyond a few specialists in the history of pragmatism (and eccentric pundits like me).

By contrast, Reinhold Niebuhr’s books are not preserved in the amber of college syllabi. As Renn notes, Obama called him his favorite theologian. Michael Mandelbaum cites Niebuhr at the outset of his 2016 book on the naive humanitarian interventionism that has shipwrecked American foreign policy. I’ve heard sermons that refer to Niebuhr’s insights. It’s not hard to imagine a young person who wants to gain a theological perspective on politics picking up Christianity and Power Politics or Christian Realism and Political Problems and reading them with a general rather than specialized interest.

What accounts for this difference? By its very nature, Dewey’s pragmatic philosophy ties him to his historical moment. Truth is whatever promotes progress, and progressive activists in 2024 have moved beyond Dewey’s concerns. His “truth” is no longer useful. Foucault and others long ago supplanted him as touchstones. Niebuhr’s work was also tied to the issues and concerns of his time. But the sinews of his thought are biblical, which means that a contemporary Christian—indeed, a secular person sensible of the biblical DNA of Western culture—can enter into his thought and draw insights.

As a professor, I often taught Introduction to Christianity. One assignment was Martin Luther’s The Freedom of a Christian. Like or dislike that short treatise, students had little difficulty reading the text and grasping its paradoxical argument. As a teacher, I reflected on this remarkable fact. How could a five-hundred-year-old book be so immediately accessible? The answer is simple: Luther uses idioms and concepts drawn from St. Paul’s letters, elements of the living language of the church. Reinhold Niebuhr was not a great theologian. But he, too, speaks the language of the church, which means that his books will be accessible and relevant for as long as the church continues to form the minds of believers.

The fates of Rorty and Neuhaus are different from those of Dewey and Niebuhr. Rorty made a big splash with his 1979 book, Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. It was a convincing attack on the formalized rationalism that was the dominant mode of philosophy in American universities. In the 1980s, Rorty wrote widely read essays that sought to develop a pragmatic philosophy akin to Dewey’s, whose reputation he championed. Truth is what works, and Rorty defines “what works” as that which enlarges and advances the achievements of American liberalism.

My copies of Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature and Consequences of Pragmatism are heavily underlined. I have relished Rorty’s fine essay on George Orwell. But I doubt that Rorty’s work will find readers in the future. Like Dewey’s, his pragmatic philosophy assigns priority to whatever brings about a better future, and thus he theorized his own irrelevance as history moves forward. Moreover, unlike Dewey, Rorty was not an activist or institution builder. (Dewey was the most significant figure at Columbia Teachers College, the institution that did a great deal to transform public education in the twentieth century.) This difference means that historians won’t feature Rorty’s name prominently in histories of late-twentieth-century American progressive politics. In histories of philosophy, I doubt that he will be much mentioned, any more than is Josiah Royce, a once famous philosopher who flourished one hundred years before Richard Rorty attained his own fleeting fame.

Richard John Neuhaus filled countless pages with his prose. He commented on church politics and secular politics, theological controversies and moral debates, cultural trends and literary masterpieces. It’s fair to say that he invented blogging avant la lettre. He perfected the art of fluid commentary on the passing scene in “The Public Square” and “While We’re At It,” columns I perpetuate, albeit with far less brio and in briefer compass. His most widely known book, The Naked Public Square (1986), defended the then-influential Religious Right as a legitimate voice in the American tradition of democratic deliberation and debate. He authored many other books, and he had his finger in numerous projects and publications over the years.

Some of Neuhaus’s output falls into the genre of highbrow journalism. He also penned works of pastoral theology, aiming to help clergy understand their vocations. He reflected on his brush with death, and he wrote about the central truths of the Christian faith. His range was broad, but his idiom was consistently theological. He therefore shares with Reinhold Niebuhr a certain timelessness, born of participation in the ongoing life of the church. Neuhaus’s meditation on the last words of Jesus from the Cross, Death on a Friday Afternoon, is exemplary in this regard. It has been and will remain a popular book. I can easily imagine that this book, unlike anything written by Richard Rorty, will be selected fifty years from now by a Christian fellowship as a basis for spiritual reflection during Holy Week. Faithful exposition of the words of Scripture does not go out of style.

Like Dewey, Neuhaus was an activist and institution builder. Possessed of a gift for friendship, he was a leader who empowered others and won their loyalty. First Thingsendures because of Neuhaus. He put his stamp on our publication: orthodox in theology, unapologetic in witness, confident in assertion, wide-ranging in interest, stern in warning, and cheerful in celebration. More importantly, he assembled around himself a community of writers and readers who carried forward his projects, interests, and passions after his death.

Most authors are swallowed by time. Nearly all that is published is foredoomed to be unread and forgotten. Those who survive are most often more than writers. Some are devoted teachers. I have no doubt that Leo Strauss endures because he inspired a cohort of brilliant graduate students, who went on to assign and discuss his books with subsequent generations. Others are activists and builders of institutions. Public schools are named after John Dewey, not because he wrote timeless treatises, but because he led the progressive educational movement. The same will hold for Richard John Neuhaus. The lasting influence of First Things is rightly seen as his legacy. And that legacy includes more than this publication. Neuhaus theorized the role of religion in public life. He advocated for it tirelessly, and he organized to ensure its perdurance. The wide array of religious writers, policymakers, and politicians (some of whom hotly insist that theological principles, properly understood, militate against positions taken in First Things) testify to his influence.

Let’s imagine an American future. It will feature Christian and Jewish communities that, though not majorities, are nevertheless vigorous and substantial. In this future, secular progressives will be seen as representatives of a discredited past. The rainbow flag will have been retired. The country won’t be a biblical republic; theocrats won’t be in charge. But in this future, men and women of faith, educated in the best traditions of the West, possessed of a flexible, capacious outlook, and able to articulate moral principles that are not the exclusive province of the religious believer, will exercise outsized influence. If this future comes to pass—it is our ambition—there is no doubt that historians will highlight the role of Richard John Neuhaus.

Christian Populism

More than three decades ago, Nathan Hatch published The Democratization of American Christianity, a history of the Second Great Awakening, arguably the most important religious episode in American history. At the recent Intercollegiate Studies Institute annual homecoming, I served on a panel that discussed the award-winning book. It was a pleasure to do so. Hatch gives a magisterial account of the upsurge of religious populism that shaped the new American republic in decisive ways. Anyone who wants to understand the last ten years of American politics should read The Democratization of American Christianity.

Denunciations of the “swamp” echo the Second Great Awakening’s polemics against the clerical establishment of its day, which itinerate preachers derided as complacent, more interested in high salaries and comfortable parsonages than in gospel preaching. Trump rallies follow in the tradition of raucous, call-and-response camp meetings. Commentators wonder at the fact that respectable people support Trump, not knowing that some of the most important leaders of the religious populism of the early 1800s were elites such as Barton Stone, who embraced the new, raw, and uncouth style of religious revival.

Elias Smith was a renegade preacher and journalist who, in 1808, launched America’s first religious newspaper, Herald of Gospel Liberty. He mocked and abused the Calvinist grandees, the “clerical hierarchy” that dominated Protestantism at that time. Establishment clergy like Lyman Beecher raged against preachers like Smith who were disturbing the religious landscape. It does not take much imagination to cast Tucker Carlson in the role of a latter-day Elias Smith. He thrills his populist devotees and outrages the guardians of political respectability such as George Will, a Lyman Beecher of our time.

Hatch raises larger themes. The Second Great Awakening took place during a time of rapid social change. The new republic gave rise to radicalisms of many sorts. People were on the move, as territories west of the Appalachian Mountains were settled. Old institutions and authorities lost their power. As I note above, recent decades have seen similar changes. Globalization, demographic change, the sexual revolution, social media, and other factors have precipitated a quite different but equally significant crisis of authority. We should not be surprised, therefore, that populism has returned, as it did in the late 1800s, when America was transformed by industrialization, urbanization, and swelling waves of immigrants.

Hatch documents that revivalist preachers were confident that their individualist, evangelical Christianity would fulfill the sacred mission of America. In their sermons and broadsides, populist religion mixed freely with populist politics, as was the case for William Jennings Bryan and subsequent American populists. Today’s Trumpian populism is different. To be sure, many pious people support Trump and other populist politicians. Avatars of popular religion like Paula White lurk on the peripheries. But the movement lacks an explicitly religious dimension, which is striking when we compare it to the administration of George W. Bush, an establishment figure who was not shy about his evangelical convictions.

Which makes me wonder: In spite of fascinating parallels to the outpouring of Christian enthusiasm and political radicalism in the Second Great Awakening, does today’s populism ironically contribute to an important elite ambition, the establishment of a post-Christian, entirely secular political culture in America? I hope not.

While We’re At It

WHILE WE’RE AT IT

- Dietrich Bonhoeffer wrote about the moral inversions that took hold in 1930s Germany. The inversions were often theologically baptized as fitting reactions to the moralizing complacency of bourgeois Christianity. Here is a sharply worded passage from his Ethics:

The justification of the good has been replaced by the justification of the wicked; the idealization of good citizenship has given way to the idealization of its opposite, of disorder, chaos, anarchy and catastrophe; the forgiving love of Jesus for the sinful woman, for the adulteress and publican, has been misrepresented for psychological or political reasons, in order to make of it a Christian sanctioning of anti-social ‘marginal existences,’ prostitutes and traitors to their country. In seeking to recover the power of the gospel this protest unintentionally transformed the gospel of the sinner into a commendation of sin.

Transgression liberates! Perversion opens new and more inclusive horizons! The mentality Bonhoeffer criticizes is very much with us today.

- Speaking of reversals: Adam Smith-Connor is being prosecuted in Great Britain. His crime? Engaging in silent prayer for his aborted son near an abortion clinic. Apparently, this act is prohibited behavior within a four-block zone around the abortion clinic. Christian piety prohibited; a temple of child sacrifice protected. Would it be harmful to the witness of the Church if a dozen priests were arrested for doing as Smith-Connor has done?

- Brad Littlejohn on the proper role of pessimism (from his regular musings, “Commonwealth Dispatches”):

We must reject the pragmatic premise that self-deceit is better than honesty if it produces better immediate results. There comes a point in every life when a man must have the clear-eyed courage to look the end of all his strivings squarely in the face, rather than listening to doctors who promise him he’ll be back on his feet in no time. For the Christian, death is not the end, either for an individual or for a civilization. We can face our cultural decline with the world-renewing vision of a Benedict or a Boethius only if we are willing to look beyond the possible death of our own social world toward the new ones the Lord may have in store.

- Oren Cass takes on the phenomenon of tiger-mom parenting. He notes that today’s parents are far more anxious to give their kids every advantage in life than they were in previous generations. But outcomes are perversely worse, not better.

Everyone agrees that parenting has gotten wildly more intensive in recent decades. The data do not provide evidence of improved outcomes. Kids are not more emotionally resilient—almost surely less so. Their mental health is worse. Their test scores are lower. Those who go to college arrive less able to handle living on their own or doing the coursework. Heck, young men’s wages are no higher than they were 50 years ago. For the first time, in the 2010s, young Americans aged 18 to 34 were more likely to be living at home with their parents than in their own home with a partner. Serious question: How much worse could we do here?

Cass makes suggestions: “Alongside the push to get phones and social media apps out of young hands, could we convert youth sports back to gaggles of kids chasing a ball around the field in town?” And what about the great scramble to get Junior into a selective university? Well-to-do parents encourage their kids to enroll in enrichment programs and take internships with save-the-world organizations, both regarded as key elements of successful college applications these days. Cass suggests refocusing admissions on standardized tests. He’s right to do so. Setting one or two hurdles in their paths leaves teenagers with a great deal more freedom to be teenagers instead of groomed thoroughbreds.

- I came of age in the 1970s. In those years, the SAT carried a great deal of weight. As a result, my sometimes-dissolute participation in boring high school classes and my imperfect compliance with class requirements were not dispositive. Moreover, Kaplan and other test prep companies were not yet perceived as necessities. One simply took the test on the assigned day. Say what you will about the “unfairness” of admission on the basis of test scores, the arrangement was a great deal less stressful than today’s system.

- The University of Pennsylvania is offering a writing seminar, “Abolish the Family.” From the course description: “In this seminar, we will look at the history of family abolition and its threads through various other movements, examine variations in cultural models of the family, and imagine new models of collective care together.” Again, the open-society consensus blesses courses like this. It tells us that the decline of mental health among the young, like all other problems, arises from overly repressive institutions. Disintegrate the family, and life will be more fluid, flexible, and fulfilling!

- As Penn indulges every fashion on the left, it punishes conservatives. After two years of disciplinary proceedings against law professor (and First Things author) Amy Wax, the university upheld the sanctions it had imposed for her “crimes,” one of which was to notice that a middle-class work ethic and self-discipline can do much to bring about success in life, another of which was to notice that affirmative action misplaces unprepared black students into academically competitive environments, which is why they often end up in the lower reaches of class rankings. These and other statements were adduced as evidence that Wax creates a “discriminatory environment,” even though no evidence has been brought forward showing that Wax has discriminated against her students.

- After lamenting the missteps of the present pontificate, a friend observed: “On the other hand, I went to the Latin Mass today at St. Rita’s in Alexandria, VA. It was standing room only, and there were so many children on the laps of so many veiled mothers, it was hard not to feel at least a little hopeful about the future of the Church.”

- In the preface to his 1989 collection of essays, The Philosopher on Dover Beach, Roger Scruton writes:

The culture of Europe, and the civilization that has sprung from it, are not yet dead. The opportunity remains to give our best to them, and to receive, in reward, the experience of belonging. For a century or more, Western man has listened to prophecies of his own decline, has been schooled in guilt and self-abnegation, and has doubted the civilizing force of his beliefs, his institutions and his way of life. Since nothing has ever been put in the place of those good things, save tinsel illusions and lawless power, the result of this self-repudiation has been a kind of active nihilism—a nihilism not of the mind and soul only, but of the forms of social life and the structures of political power.

I dare say that active nihilism has gotten stronger in the ensuing decades (“Abolish the family!”). Still, opportunities for recovery and restoration remain. Indeed, they have perhaps multiplied, as the proliferation of schools dedicated to classical education suggests and my friend’s observations about the Latin Mass indicate. What’s needed these days is an active piety, a spirit of affirmation devoted to repair, that faces down active nihilism.

- New York Times religion writer Ruth Graham reports on the growing gaps between men and women. Gen-Z men are less likely to graduate from college than their female peers. In many major cities, they earn less than women. There’s a countertrend, however: Young men are spiritually ahead of their female peers. Graham: “It is young men who now register higher in attachment to basic Christian beliefs, in church attendance and in frequency of Bible reading.” They place a higher value on family life, as well. Graham notes a recent Pew survey: “Childless young men are likelier than childless young women to say they want to become parents someday, by a margin of 12 percentage points.” Young men are more conservative politically, overwhelmingly more likely to vote for Trump than Harris. Young women break in the opposite direction. Overall, it seems that the rising generation of women is increasingly loyal to the progressive promise that life’s greatest satisfactions are material: career, travel, consumption. Young men are turning in a different, countercultural direction. I fear that the war between the sexes is likely to get worse, not better.

- Kamala Harris has largely refrained from staking out policy positions—except on the question of abortion-on-demand. In a September 23 interview, she advocated for encoding into federal law the abortion-on-demand regime that held sway under Roe. Here is what she said:

I think we should eliminate the filibuster for Roe, and get us to the point where 51 votes would be what we need to put back into law the protections for reproductive freedom and for the ability of every person and every woman to make decisions about their [sic] own body and not have their [sic] government tell them [sic] what to do.

Donald Trump’s betrayals of the pro-life cause are disappointing. Harris’s enthusiasm for abortion, shared by far too many Democrats, is chilling.

- On September 20, senior editor Julia Yost and regular columnist Liel Leibovitz joined me for our first-ever Editor’s Circle webinar. Our theme was “The Promise of Renewal.” Where do we see the active piety that I describe above, the antidote to active nihilism? The Editor’s Circle is our community of core supporters. To learn more and make an Editor’s Circle gift, visit supportfirstthings.com/EC.

- I’m pleased to announce that Veronica Clarke will serve as deputy editor, overseeing our web publications. Vicky was a junior fellow from 2019 through 2021, and she has served as associate editor for the last three years.

- Nathaniel Stanley of Bangor, Maine seeks to form a ROFTers group. To become a founding member, contact him at nathaniel.stanley@maine.edu.

Is Trump Playing the Long Game on Abortion?

When news broke last week that the Trump administration had quietly restored federal Planned Parenthood funding, which…

The Rise and Fall of Gay Activism

The Pride flag is progressive America’s banner. Before it was unfurled, most gays stayed in the closet.…

Self-Destructive Liberalism (ft. Philip Pilkington)

In the latest installment of the ongoing interview series with contributing editor Mark Bauerlein, Philip Pilkington joins…