It’s the puzzle of the 2016 Presidential race. It’s the question that’s dominating European politics in the aftermath of Britain’s exit from the EU and after a summer of immigration turmoil. Everything was going so swimmingly toward a global future. Everyone seemed so happy. Suddenly, so it seems, nationalism, patriotism, Firstism are breaking out all over. It used to be Obama and Clinton and Cameron and Merkel; now it’s all Trump and Farage and Le Pen.

What happened?

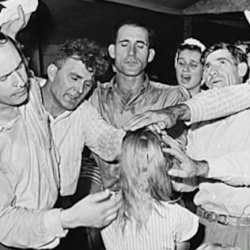

Immigration has been the catalyst. As NYU’s Jonathan Haidt puts it in an illuminating piece in the American Interest, “immigration has been so central in nearly all right-wing populist movements. It’s not just the spark, it’s the explosive material.” To many, the populist/nationalist response to immigration is a fresh wave of fascism, a frightening resurgence of overtly racist ideologies that we fondly believed had been purged.

That, Haidt argues, is wrong-headed, oversimplifying by leaving out the dynamics of “moral psychology.” In fact, the charge of racism is the very kind of thing that fans the fires of populist nationalism: “globalization and rising prosperity have changed the values and behavior of the urban elite, leading them to talk and act in ways that unwittingly activate authoritarian tendencies in a subset of the nationalists.”

Many analysts get the cart before the horse. Before we can understand the populist/nationalist resurgence, Haidt says, we must understand what’s happened to Western elites. Not too awfully long ago, slogans like “American jobs for Americans” were boilerplate on both sides of the political spectrum. Why has that become problematic?

Haidt takes a long view. Industrialization moves nations away from traditional values and authorities toward “secular rational” values and autonomy. As nations become wealthy, they leave behind “survival values.” They begin pursuing “self-expression” and “emancipation.” Thus, Haidt suggests, “As societies become safer and more prosperous, they generally become more open and tolerant. Combined with the vastly greater access to food, movies, and consumer products of other cultures brought to us by globalization and the internet, this openness leads almost inevitably to the rise of a cosmopolitan attitude, usually most visible in the young urban elite.”

In support, he cites Christian Welzel’s theory of emancipation (Freedom Rising), which claims that rising wealth leads nations to “prioritize freedom over security, autonomy over authority, diversity over uniformity, and creativity over discipline.” When you don’t have to worry about survival, you can climb what Welzel calls the “utility ladder of freedoms.” Freedoms that were once luxuries become useful, threats are transformed into opportunities, and so secure and prosperous nations seek and expanding set of entitlements and guarantees of those freedoms.

This produces some ironies. Global elites themselves adhere to a strong set of norms—equality, autonomy—that are threatened by traditionalist Muslims, but their code requires them to tolerate Muslims. The irony ties them up in knots. In hyper-tolerant Sweden, Haidt observes, some swimming pools now have sex-segregated hours to accommodate Muslims. Egalitarians thus make space, in the name of equality and tolerance, for the intolerant.

The problem is, security isn’t evenly distributed. As Welzel puts it, not everyone has equal access to “action resources” or an equal ability to act at will. Thus, Haidt writes, “persistent existential pressures keep people’s minds closed, in which case they emphasize the opposite priorities.” The sectors of society that are more secure, prosperous, and free are open to “tolerance and solidarity beyond one’s in-group,” while the “existentially stressed state of mind is the source of discrimination and hostility against out-groups.”

Stressed groups can’t climb the ladder of freedoms, and don’t see any utility in expanding the menu of lifestyle options. They are less tolerant than their more secure countrymen. Their intolerance may be directed against people of other races, but, Haidt argues, racism can’t explain their reaction: “racism usually turns out to be deeply bound up with moral concerns. . . . People don’t hate others just because they have darker skin or differently shaped noses; they hate people whom they perceive as having values that are incompatible with their own, or who (they believe) engage in behaviors they find abhorrent, or whom they perceive to be a threat to something they hold dear.”

Haidt depends on Karen Stenner’s 2005 book, The Authoritarian Dynamic, which claims (in Haidt’s summary) that “authoritarianism is not a stable personality trait. It is rather a psychological predisposition to become intolerant when the person perceives a certain kind of threat. It’s as though some people have a button on their foreheads, and when the button is pushed, they suddenly become intensely focused on defending their in-group, kicking out foreigners and non-conformists, and stamping out dissent within the group.” That button gets pushed when people perceive a “normative threat.”

In Stenner’s own words, this is “the experience or perception of disobedience to group authorities or authorities unworthy of respect, nonconformity to group norms or norms proving questionable, lack of consensus in group values and beliefs and, in general, diversity and freedom ‘run amok’ should activate the predisposition and increase the manifestation of these characteristic attitudes and behaviors.”

It’s wrong, Haidt argues, to charge authoritarians with being selfish: “They are not trying to protect their wallets or even their families. They are trying to protect their group or society.” To be sure, “some authoritarians see their race or bloodline as the thing to be protected, and these people make up the deeply racist subset of right-wing populist movements, including the fringe that is sometimes attracted to neo-Nazism.” But many are reacting to threats that have little to do with race, and everything to do with moral disruptions and the perception that moral order is decaying.

Even physical threats aren’t at the core of the reaction. Europeans and Americans distrust Middle East immigrants not only or primarily because they may be terrorists; they distrust them because the believe Islam demands a way of life that is incompatible with American and European norms. Haidt observes that non-nationalist conservatives, who simply want to curtail the pace of social change, will join with populists when they perceive a threat to moral order.

Here’s where tolerant elites make matters worse: “whether you are a status quo conservative concerned about rapid change or an authoritarian who is hypersensitive to normative threat, high levels of Muslim immigration into your Western nation are likely to threaten your core moral concerns. But as soon as you speak up to voice those concerns, globalists will scorn you as a racist and a rube.” Elites respond to populism by insisting that we should broaden the scope of our toleration. But that is precisely what pushed the “authoritarian” button in the first place.

Stenner puts it this way: “[T]he increasing license allowed by those evolving cultures generates the very conditions guaranteed to goad latent authoritarians to sudden and intense, perhaps violent, and almost certainly unexpected, expressions of intolerance. Likewise, then, if intolerance is more a product of individual psychology than of cultural norms . . . we get a different vision of the future, and a different understanding of whose problem this is and will be, than if intolerance is an almost accidental by-product of simple attachment to tradition. The kind of intolerance that springs from aberrant individual psychology, rather than the disinterested absorption of pervasive cultural norms, is bound to be more passionate and irrational, less predictable, less amenable to persuasion, and more aggravated than educated by the cultural promotion of tolerance.”

Haidt applies his analysis to immigration: “Think carefully about the way your country handles immigration and try to manage it in a way that is less likely to provoke an authoritarian reaction. Pay attention to three key variables: the percentage of foreign-born residents at any given time, the degree of moral difference of each incoming group, and the degree of assimilation being achieved by each group’s children. . . . Moderate levels of immigration by morally different ethnic groups are fine . . . as long as the immigrants are seen as successfully assimilating to the host culture. When immigrants seem eager to embrace the language, values, and customs of their new land, it affirms nationalists’ sense of pride that their nation is good, valuable, and attractive to foreigners. But whenever a country has historically high levels of immigration, from countries with very different moralities, and without a strong and successful assimilationist program, it is virtually certain that there will be an authoritarian counter-reaction, and you can expect many status quo conservatives to support it.”

Stenner’s conclusion is similar: “all the available evidence indicates that exposure to difference, talking about difference, and applauding difference – the hallmarks of liberal democracy – are the surest ways to aggravate those who are innately intolerant, and to guarantee the increased expression of their predispositions in manifestly intolerant attitudes and behaviors. Paradoxically, then, it would seem that we can best limit intolerance of difference by parading, talking about, and applauding our sameness . . . . Ultimately, nothing inspires greater tolerance from the intolerant than an abundance of common and unifying beliefs, practices, rituals, institutions, and processes.”

Which, curiously enough, is what the Firsters want to talk about.

Haidt’s essay is, as I say, very illuminating, a convincing challenge to the knee-jerk charge of racism. But a few caveats in conclusion. First, it’s not clear to me why Haidt and Stenner use the charged term “authoritarian” to describe reactions to the perceived decay of moral order. “Moralist” also has negative connotations, but seems to capture the argument more accurately.

More importantly: While Haidt refutes the equation of nationalism/populism and racism, that doesn’t exonerate nationalism/populism ethically or theologically. Even if nationalism isn’t racist, it may still be idolatrous and a challenge to the church. Since as it conflicts with Christian’s membership in a global communion, and contradicts with Jesus’ command to love our neighbors, the nationalism/populism reaction is a temptation to be resisted. Liberal tolerance isn’t the only basis for advocating justice for strangers.

Can we resist it? The evidence isn’t encouraging, but even in the pressure cooker of Nazism, some German Christians resisted.

At the same time, Christians should also resist the lure of security. Cultural norms matter, and complete relativism in cultural norms is a fundamental threat to social order. Can we resist that? Welzel doesn’t think so. Cultural norms can’t withstand the tsunami of emancipative values; cultural norms instead adjust to the new freedoms. We can see it before our eyes, as support for gay marriage and transgender rights have quickly become normative.

No doubt I’m revealing my place among the emancipated by saying that the moment presents an opportunity for Christians, an opening to articulate a public stance that rejects both blithe indifference to moral order and populist reaction.