In a TLS essay on the Welsh poet David Jones, A.N. Wilson traces Jones’s poetic impulses back to World War I: “The First World War in general, the Battle of the Somme in particular, became Jones’s imaginative habitation for the rest of his life, as a visual artist and as a poet. In a prescient note to his Somme poem, In Parenthesis, he describes how, even in 1917, he and a friend (Leslie Poulter) imagined tourists traipsing over the battlefield—‘I recall feeling very angry about this, as you do if you think of strangers ever occupying a house you live in.’”

Wilson compares Jones to William Blake: “Jones left a triple legacy: he was a visual artist of supreme originality and skill . . . . He was secondly a poet of genius. W. H. Auden believed that Jones’s The Anathemata was ‘very probably the finest long poem written in English this century.’” Finally, and most Blakean, Jones was a “visionary,” one might almost say, a mystic.

The mystical vision infuses the poetry. Of Anathemata, Wilson writes that it “can be read as a sort of patchwork or commonplace book – Arthurian legend, Stone Age archaeology, Romano-British history, woven into thoughts about the origins of the Eucharist. Read it more than half a dozen times, however, and the randomness of the offerings seems less random; the connections begin to make sense; one thing in history illuminates another, whether it antedates or post-dates it in linear time.” It is “a Christian cathedral of allusions, memories, speculation—is to see the all-embracing significance of the Event stretching forwards and backwards.”

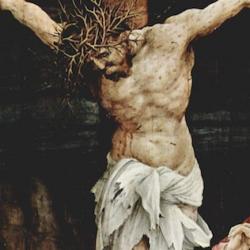

And it is a cathedral in which everything coheres at one point: “the sixth-century BC carving of Rhonbos on the Acropolis, an exquisite marble depicting a man carrying a calf on his shoulders, is seen as a foreshadowing of the Good Shepherd. Hector dragged round the walls of Troy is a type of Christ’s suffering outside the walls of Jerusalem. Helen of Troy, Guinevere, or ‘Gwenhwyfar’ in Welsh, and the Selene of Thule, all manifestations of what Goethe would have called ‘das Ewig-Weibliche,’ allude to, and find their true fulfilment in, the Christian Theotokos.”