Identity politics has weakened national identity, but it hasn’t destroyed it. As Jean and John Comaroff put it (Theory from the South), “the fractal nature of contemporary political personhood, the fact that it is overlaid and undercut by a politics of difference and identity, does not necessarily involve the negation of national belonging. Merely its uneasy, unresolved, ambiguous coexistence with other modes of being-in-the-world. It is this inherent ambiguity, we suggest, that makes the ostensible concreteness of concepts like ‘citizenship’ and ‘community’ so alluring.”

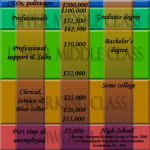

Not all identities are equal. Cultural identities are widely believed “to run deepest.” But this takes an odd turn, as culture and identity come to be views as “intellectual property . . . even more, as a naturally copyrighted collective possession—and what is the result? It is the dawn of the Age of Ethnicity, Inc.”

The Comaroffs offer these specifics in evidence: “Observe, in this regard, that many ethnic groups have formally incorporated as limited companies; that a large number of others have established themselves remunerated reproduction of their symbols, sacred and secular. Thus it is that identity, in the age of partible, conditional citizenship, is defined ever more by the capacity to possess and to consume; that politics are treated ever more as a matter of individual or collective entitlement; that social being in general, and social wrongs in particular, are translated ever more into the language of rights.”

While “multiculturalism” corrodes national identities, the cultural entities depend on the legal resources of the nation-state to protect themselves, and they market themselves in the global economy. It may begin as a gesture of resistance to “global capitalism” and “liberal order,” but multiculturalism preserves itself only by its embeddedness in those global systems.

Still, these developments have disrupt the liberal state. Multiculturalism shouldn’t be reduced to the “benign indifference to difference.” Rather, it exposes the “critical limits of liberal pluralism: that, notwithstanding the utopian visions of some humanist philosophers, the tolerance afforded to culture in modernist polities falls well short of allowing claims to autonomous political power or legal sovereignty.” In what the Comaroffs call “postcolonies,” “ethnic assertion plays on the simultaneity of primordial connectedness, natural right, and corporate interest,” and this means that the nation-state is less multicultural than it is policultural,” with the prefix denoting both “plurality and its politicization.”