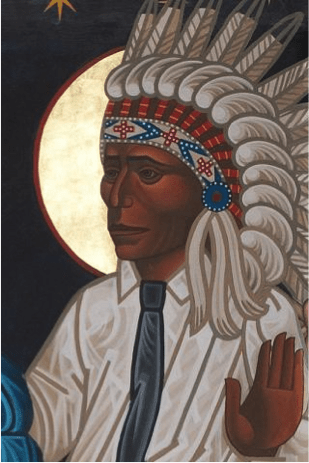

A mong the more adventurous sallies in church décor in recentmemory is the dancing saints sequence at San Francisco’s Saint Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church, where Hypatia, Charles Darwin and William Blake among others have been drafted into the communio sanctorum. Perhaps the program is less a declaration than a prayer, illustrating Hans Urs von Balthasar’s dictum that universalism is a hope though not a doctrine. But if so, wouldn’t a message of God’s universal love necessitate the inclusion of a figure or two who would rankle San Francisco Episcopalians? Still, there are many in the sequence who should long ago have been visualized in the context of Christian worship, and one especially justified inclusion is the Native American visionary Nicholas Black Elk (1863-1950).

mong the more adventurous sallies in church décor in recentmemory is the dancing saints sequence at San Francisco’s Saint Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church, where Hypatia, Charles Darwin and William Blake among others have been drafted into the communio sanctorum. Perhaps the program is less a declaration than a prayer, illustrating Hans Urs von Balthasar’s dictum that universalism is a hope though not a doctrine. But if so, wouldn’t a message of God’s universal love necessitate the inclusion of a figure or two who would rankle San Francisco Episcopalians? Still, there are many in the sequence who should long ago have been visualized in the context of Christian worship, and one especially justified inclusion is the Native American visionary Nicholas Black Elk (1863-1950).

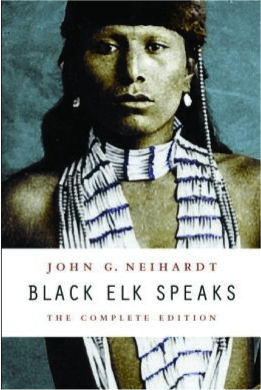

As anyone familiar with the annals of the American West will know, the life story of this Lakota mystic might have been lost, had he not divulged it to the American writer John Neihardt, resulting in the American classic Black Elk Speaks. Generations of seekers have poured over its contents, many of them seeking a release from the presumably narrow confines of traditional Christianity. But the story of Black Elk is in fact far more complicated than most such seekers, or even John Neihardt himself, assumed.

Black Elk’s first visionary experience occurred during a bout of illness when he was nine years old. Neihardt masterfully relates how the boy was transported to Harney Peak, above what is now Mount Rushmore, where he “saw in a sacred manner the shapes of all things in the spirit….” North American Christians rightfully wrestle with Plato, but how many of them know that a similar pre-Christian witness to the “real world behind this one” emerged from their own continent as well?

As the book continues, Black Elk struggles to reconcile his childhood vision with the decimation of his people in the wake of settlement – but a breakthrough came with the Ghost Dance. This mysterious fusion of Christianity and native religion swept through the Badlands of South Dakota, led by a Paiute Indian named Wovoka about whom we still know very little. Participating in the Ghost Dance as an adult, Black Elk found it corresponded to his childhood vision. While dancing, he fell into ecstasy and entered the spiritual world again. Neihardt’s account of what Black Elk saw reads like the book of Revelation:

I saw the holy tree full of leaves and blooming… But that is not all I saw. Against the tree there was a man standing with arms held wide in front of him. I looked hard at him, and I could not tell what people he came from. He was not a Wasichu [white man] and he was not an Indian. His hair was long and hanging loose, and on the left side of his head he wore an eagle feather.… While I was staring hard at him, his body began to change and became very beautiful with all colors of light, and around him there was light. He spoke like singing: ‘My life is such that all earthly things belong to me. Your father, The Great Sprit, has said this. You too must say this.” Then he went out like a light in a wind.

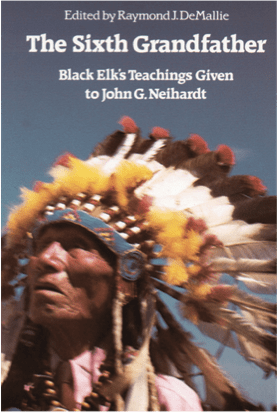

Secular historians may snicker at early Christians who insisted Virgil’s Fourth Eclogue was a vision of the Messiah, but the case for interpreting Black Elk’s vision that way is not so easy to dismiss. Raymond DeMallie, founder and director of the American Indian Studies Research Institute, has delved into the transcripts of what Black Elk originally divulged to Neihardt. DeMallie’s definitive study shows the association with Jesus in this culminating passage to be unavoidable. Black Elk also said that the transfiguring figure he saw had “holes in the palms of his hands.” In addition, Black Elk flatly asserted to Neihardt, “It seems to me on thinking it over that I have seen the son of the Great Spirit himself.” In short, Native America’s most famous vision quest culminated in a vision of Jesus; and Neihardt, universalist that he was, did not quite tell it like it was told to him.

Secular historians may snicker at early Christians who insisted Virgil’s Fourth Eclogue was a vision of the Messiah, but the case for interpreting Black Elk’s vision that way is not so easy to dismiss. Raymond DeMallie, founder and director of the American Indian Studies Research Institute, has delved into the transcripts of what Black Elk originally divulged to Neihardt. DeMallie’s definitive study shows the association with Jesus in this culminating passage to be unavoidable. Black Elk also said that the transfiguring figure he saw had “holes in the palms of his hands.” In addition, Black Elk flatly asserted to Neihardt, “It seems to me on thinking it over that I have seen the son of the Great Spirit himself.” In short, Native America’s most famous vision quest culminated in a vision of Jesus; and Neihardt, universalist that he was, did not quite tell it like it was told to him.

Black Elk’s vision of the transfigured glory of Christ, moreover, bore fruit. In his aim to have his informant encapsulate the tragic defeat of the Plains Indians, Neihardt ended Black Elk Speaks on a famously pessimistic note, strangely oblivious to Black Elk’s role, following his conversion to Catholicism, as rancher, patriarch, missionary and Catechist for the Catholic Church. One missionary estimated that Black Elk made up to four hundred converts to Christianity.

In attempting to reconcile Lakota and Christian wisdom, there were features of indigenous religion that Black Elk repudiated – specifically its violence. His original vision, which was not all sweetness and light, instructed him to use the bad medicine of soldier weed to wipe out his enemies – men, women and children. As DeMallie put it, Black Elk “refused to take responsibility for such wholesale destruction, so he give it all up and became a Catholic.” Still, when the actual soldiers of the Seventh Cavalry – Custer’s old regiment – massacred nearly 300 Indians associated with the Ghost Dance at Wounded Knee Creek (more than half of whom were women and children), they used precisely the methods that Black Elk, in the name of Jesus, had renounced.

In attempting to reconcile Lakota and Christian wisdom, there were features of indigenous religion that Black Elk repudiated – specifically its violence. His original vision, which was not all sweetness and light, instructed him to use the bad medicine of soldier weed to wipe out his enemies – men, women and children. As DeMallie put it, Black Elk “refused to take responsibility for such wholesale destruction, so he give it all up and became a Catholic.” Still, when the actual soldiers of the Seventh Cavalry – Custer’s old regiment – massacred nearly 300 Indians associated with the Ghost Dance at Wounded Knee Creek (more than half of whom were women and children), they used precisely the methods that Black Elk, in the name of Jesus, had renounced.

Whether at Wounded Knee or through the Indian Boarding School movement that followed it, American Christians did their best to eradicate native culture. Surely this is part of why Black Elk found John Neihardt, or later Joseph Epes Brown to be more attentive recorders of Lakota wisdom, and we should be grateful to both of them. Today, however, Christianity is proving a far more dignified carrier for native wisdom that the New Age movement upon which it has lately been grafted. The Holy Rosary Mission on the Pine Ridge Reservation has matured into the Red Cloud School where native culture flourishes, and medicine wheels have been elegantly worked into Catholic architecture. Richard Twiss’s posthumous publication promises to continue evangelical interest in native culture. Charles Chaput, the Native American archbishop of Philadelphia, and Blase Cupich, archbishop of Chicago, both emerged from the diocese of Rapid City which sponsors weekly powwows alongside Woyatan Lutheran Church. Finally, in the wake of Kateri Tekakwitha’s canonization, Laudato Si’ makes references to mother earth less pagan than papal. Whatever is to be said about the encyclical, its constant refrain, “everything is connected,” is no empty slogan – on the contrary, it echoes that famous encapsulation of Lakota wisdom, Mitakuye Oyasin (“all are related”).

Black Elk, who first met Jesus in a dance-induced trance, anticipated and would likely be pleased by each of these developments. But non-native Christians should be interested as well. All who walk into church through classical columns are benefitting from a thoroughly Christianized paganism. Why should assimilation have stopped with the Latins and Greeks? “Only time will tell if [Christianity] is the right thing for our people,” says an Ojibwa elder in Ignatia Broker’s Night Flying Woman. “If it is, then the people who wish us to be baptized will some day come to know the goodness that has been our life.”

Matthew Milliner (@millinerd) is assistant professor of art history at Wheaton College.

Become a fan of First Things on Facebook, subscribe to First Things via RSS, and follow First Things on Twitter.

In the Footsteps of Aeneas

Gian Lorenzo Bernini had only just turned twenty when he finished his sculpture of Aeneas, the mythical…

The Clash Within Western Civilization

The Trump administration’s National Security Strategy (NSS) was released in early December. It generated an unusual amount…

Fanning the Flames in Minnesota

A lawyer friend who defends cops in use-of-force cases cautioned me not to draw conclusions about the…