Since its founding, the United States has elicited much curiosity and commentary from European intellectuals. Oscillating between paternal interest and fraternal rivalry, Europe’s ambitious scribes have braved the Atlantic, written sprawling books, instructed us in manners and morals, and measured our development against Old World benchmarks. Sometimes this interest has been positive, sometimes ambivalent; often, especially in recent years, it has been negative and condescending.

The French, in particular, have commented prodigiously on America. From Talleyrand and Tocqueville to Jean Baudrillard and Bernard-Henri Lévy, French thinkers have left lasting guideposts of interpretation, if not always on the actual America of Iowa City and Cleveland then at least on the symbolic America, that golem of soulless modernity.

As the process of post–Cold War European unification unfolded, hostility to this symbolic America unfortunately helped define the new European identity. Where then might one turn to find a more measured view from abroad? The French philosopher Jacques Maritain provides an interesting starting point. His picture of the nation, as glimpsed in Reflections on America (1958), offers a sympathetic treatment of the United States, one that deftly mixes historical insight and theological reflection.

Such a treatment by a French Catholic did not appear likely in the middle of the twentieth century. As an expression of political modernity, the United States long stood under a cloud of suspicion for devout Catholics, who in the nineteenth century tended to associate liberal ideas with the French Revolution’s anticlericalism. Moreover, Catholic misgivings cannot be isolated from more-general Old World elite hostility toward an upstart nation. This hostility waxed and waned through the nineteenth century, reaching a high-water mark in the early twentieth century as the United States’ industrial clout grew. The politically polarized interwar years saw a high volume of anti-American literature published in Europe. Georges Duhamel’s French bestseller, America the Menace (1930), expressed a typical loathing of commerce, crowd culture, and entertainment in America. Three years before Hitler ravaged Europe, Duhamel saw in the United States nothing but the brutalization of conscience, the standardization of culture, and the debasement of civilized values.

Unlike many commentators, Maritain and his wife Raïssa actually lived in the United States. He fled war-torn Europe in 1940 for what was to be a brief exile. As things turned out, he accepted academic appointments in New York and Princeton and wound up living in the United States until 1960 (punctuated by three years as French ambassador to the Vatican after the war).

In Reflections on America, European elite criticism of the United States is never far from Maritain’s mind. When unwarranted, he contravenes it; when justified, he presents it shorn of the more general antipathy toward America. Throughout, he speaks in a transatlantic voice, neither American nor European. Still, he exhibits the affection of a grateful refugee and divines in the American constitutional order elements of what he sought to articulate theoretically in Things That Are Not Caesar’s, Integral Humanism, Man and the State, and other works of political philosophy.

That Americans lack any sense of history was a refrain among European critics. Maritain did not categorically dispute this charge, but he gave it a more nuanced valuation. He saw “openness to the future” as a salutary consequence of America’s historical conditions. In Europe, recent calamities amounted to an “overwhelming historical heredity,” a “sclerosis,” and openness to the future did not necessarily mean that Americans lacked historical awareness.

Maritain was struck by the ongoing vitality of America’s founding era. A living past, instead of an exhausted one, and a palpable sense of a future amenable to human initiative appeared to him to have inoculated Americans from continental ideologies claiming “historical necessity.” Accordingly, he posited a “root incompatibility” between the American people and Marxism. “For Marx,” he elaborated, “history is . . . [a] set of concatenated necessities, in the bosom of which man slaves toward his final emancipation. When he becomes at last, through communism, master of his own history, then he will drive the chariot of the Juggernaut which had previously crushed him. But for the American people it is quite another story. They are not interested in driving the chariot of the Juggernaut. They have gotten rid of the Juggernaut. It is not . . . in mastering the necessities of history, it is in man’s present freedom that they are interested.”

Maritain sought to rebut the frequent charge that Americans were peculiarly given to materialistic pursuits. He did not deny that untoward attachments to consumer goods characterized the postwar industrialized world, but he wondered if Americans, in some respects, were the least materialistic among the wealthy nations. The reproach of materialism did not derive from empirical evidence, he felt, but drew its strength from an Old World elitist tradition of “confusing spirituality with an aristocratic contempt for any improvement in material life.” This elitist critique-perfected “among certain high-brow Europeans with large bank accounts and delicious wine in their cellars””exerts such a powerful moralistic appeal that “you yourselves [Americans] are taken in by it.”

In the spirit of Tocqueville, Maritain replied by calling attention to the “infinite swarming” of private charities, foundations, and schools. The enormous creative energy of the American private sector, in generating wealth and giving it away, constituted for him an epochal boon to human flourishing. While he admired America’s largest foundations, “born of freedom and immune from state control,” he equally praised the philanthropic spirit of average Americans—something that might help explain what Arthur C. Brooks of Syracuse University has called “the huge transatlantic charity gap,” with Americans giving away, per capita, considerably more than do their European counterparts.

In his political thought, Maritain esteemed modern democracy for its potential to express the Judeo-Christian belief in the dignity of the individual. For him, the United States added something significantly to the theological underpinnings of democracy: immigration, a nation conjured up by peoples once persecuted, rejected, and humiliated. The cultural memory of past suffering coupled with a chance to make good in a New World had deposited “a reminiscence of the gospel in the inner attitude of people” and a resolve that misery and want need not be the accepted lot. “Here lies a distinctive privilege of this country, and a deep human mystery concealed behind its power and prosperity. The tears and suffering of the persecuted and unfortunate are transmuted into a perpetual effort to improve human destiny . . . . [T]hey are transfigured into optimism and creativity.”

Maritain championed the American experiment in “voluntary” religion: a new thing in history, he believed, and distinct from many European church-state arrangements. In Integral Humanism (1936), he had argued for a secular polity in which people of diverse religious backgrounds worked for the common good, albeit in a constitutional framework inspired by an implicitly theological sense of natural law and the dignity of the individual. He felt this to be a proximate reality in the United States.

As he expressed it in Man and the State (1951): “A European who comes to America is struck by the fact that the expression ‘separation between Church and State’ . . . does not have the same meaning here and in Europe. In Europe it means . . . complete isolation which derives from century-old misunderstandings and struggles, and which has produced most unfortunate results. Here it means . . . a distinction between the state and the churches which is compatible with good feeling and mutual cooperation . . . . There’s a historical treasure, the value of which a European is perhaps more prepared to appreciate, because of his own bitter experiences. Please to God that you keep it carefully, and do not let your concept of separation veer round to the European one.”

While America’s religious settlement represented a dramatic departure from the Old World, Maritain regarded the whole of its constitutional order truly as a novus ordo seclorum . But he did not locate its origins strictly in English common law or Enlightenment thought. It reflected the older classical and medieval conceptions of natural law and a flourishing polity. His line of reasoning here strikingly parallels that of John Courtney Murray’s in We Hold These Truths (1960). Not bonds of necessity, but the decisions of free men, Maritain maintained, characterized the good state for Aristotle and Aquinas. Theirs is a community based on virtue and reason, and “implies a will or consent to live together . . . . Nowhere in the world has this notion of the essence of political activity been brought into existence more truly than in America.” Since he located his own political thought in the Aristotelian-Thomistic tradition, the United States appeared as the fortuitous historical approximation of realities that he had long theorized about.

Accordingly, he felt that the United States had a special role to play in the postwar world. Nowadays, when many educated American Christians are inclined to equate political theology with prophetic jeremiads against liberal democracy, the language of America’s historical role might appear dangerously providentialist. And due caution is in order, given the abuse of providentialist claims in American history. But, as an outsider to America and a trenchant observer of Europe’s political convulsions, Maritain cannot be easily brushed aside.

He insisted on the “the obvious fact” of America’s uniqueness. This was not a nation based on race, language, and geography but on a proposition that diverse peoples could live in freedom and preserve, in a modern secular order, a vital residuum of the classical-Christian natural-law tradition as a guarantor of human dignity. Upholding this dignity”the dignity of the least among us”constituted America’s historic vocation, even if this meant, as in the civil rights movement, “a perpetual process of self-examination and self-criticism.” This might not constitute a high calling, understood as producing great culture or art. Chicago is not Paris, Maritain admitted, but “there is one thing that America knows well”: “the value and dignity of the man of common humanity . . . . In forms so simply human that the pretentious and pedantic are at pains to perceive it, we find a spiritual conquest of immeasurable value.”

Maritain connected this “spiritual conquest” to what he had earlier called a “new Christendom”—not the coercive medieval order, but a progressive world system of democratic states, appreciative of the historical influence of the gospel on modern freedoms. At pains to make clear he was advocating a way forward, not the restoration of the deservedly obsolete, Maritain reiterated that he was “far from saying that today’s American civilization is a new Christendom, even in outline. It is rather a combination of certain continuing elements of ancient Christian civilization with new temporal achievements and new historical situations.” To bring about this new order in the postwar world, the American experiment was pivotal. “If we want civilization to survive,” he wrote during the darkest period of World War II, the “American spirit” must help lead the way in creating “a world of free men penetrated in its secular substance by a real and vital Christianity, a world in which the inspiration of the gospel will direct the common life of man toward an heroic humanism.”

Maritain recognized that his proposition would be mocked by pro-socialist, anti-American voices in postwar Europe and obscured in America by unsavory forms of patriotism. He also candidly recognized that the religious element in American civilization could degenerate into impermissible forms of civil religion, instrumentalizing Christianity for “national or temporal interests.” He adamantly opposed this, insisting that Christianity was essentially otherworldly; when it touched the realm of Caesar, it did so as a salutary leaven, not as a fundamental substance.

But he also worried about Europe’s secularist drift, a growing animus toward any religious leaven. “Europe’s problem is to recover the vivifying power of Christianity in temporal existence,” Maritain had presciently written in the 1940s, for without this power the machinery of democracy might go on, but the individuals in it will be stripped of the transcendental justification of their dignity.

In light of his assessment of Europe, it is telling that Maritain worried about the obsequiousness with which American intellectuals looked to the Continent for intellectual direction. The “cultivated American,” who is “anxious to have America criticized,” listens with “special care and sorrowful appreciation” to “any [European] writer who bitterly denounces the vices of this country.” This did not augur well for his ideas. Still, to American audiences, he pled for “the need for an explicit philosophy” that would extrapolate American political arrangements and sensibilities into a philosophical ideal, the centerpiece of which was the inviolability of human dignity.

To be sure, those concerned about the life of the mind on these shores might justifiably ask whether taking Maritain at his word, once again, risks indulging our craving for continental tutelage. But why not make a virtue of our national docility? The reign of Marx, Sartre, and Foucault has passed. Derrida is dead. The age of Maritain—has its hour come round at last?

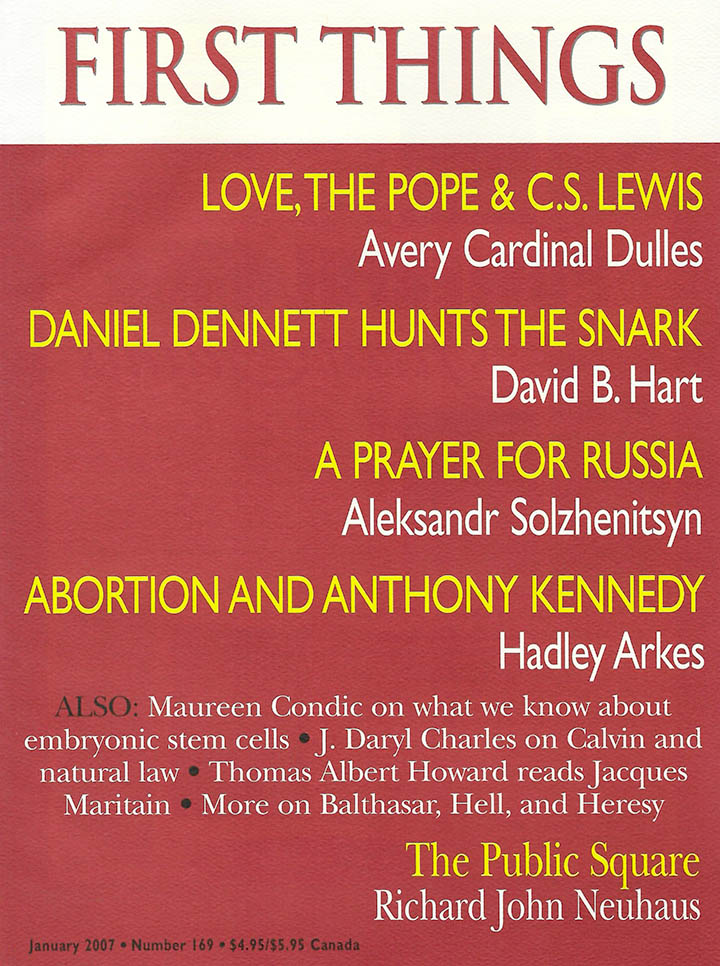

Thomas Albert Howard is an associate professor of history and the director of the Jerusalem & Athens Forum at Gordon College in Wenham, Massachusetts. He is currently at work on a book, America, Europe, and the Transatlantic Religious Divide.