The political winds are shifting, and our elites are increasingly dismayed and disoriented. Voters throughout the West are rejecting establishment parties, often in spite of dire warnings by the mainstream media and the leadership class. The European Union, supposedly a template for a more prosperous and peaceful future, is being challenged by upstart politicians and renegade nations. Yet these challenges have not led to famine, war, or depression. An American can fly to Budapest without a visa and dip his card into the cash machines without difficulty. The same holds for Brexit. One can fill volumes with predictions of the disasters that will ensue if Great Britain persists in forging its own fiscal, trade, immigration, and cultural policies. Perhaps terrible things will come to pass. But life on the ground suggests otherwise. The most likely result of Brexit will be a modest reshuffling of economic winners and losers in a British economy that remains deeply integrated into the global system, and a moderate cultural rebalancing in the direction of national solidarity.

We observe a growing divide between reality and rhetoric. Stock markets rise; the interlocking global economic system hums; nations lose their minds during sporting matches. Yet despite so many signs of normalcy, prestige newspapers and magazines trumpet the dangers of fascism at home and neo-Bolshevism abroad. In the once staid pages of the New Yorker, Masha Gessen warns, “Do not be taken in by small signs of normality.” One year in, the Trump presidency may not seem as great a threat to democracy as so many predicted, including Gessen. But do not be deceived! He is an autocrat in the making, and our most cherished liberal traditions are imperiled.

Why the hysteria? There are real problems in our society. The decline in life expectancy in the United States suggests as much. But communities ravaged by heroin overdose deaths do not organize marches and protests. Young people with crushing student loan debt are not burning their monthly invoices, as their grandfathers once burned their draft cards. Polls show historically low levels of approval for Congress and other political institutions, and voters are in a truculent mood when they go to the polls. But they are not in the streets. For the most part, they get on with their everyday lives. Meanwhile, columnists, pundits, and those responsible for shaping public opinion wax apocalyptic (although they too get on with their everyday lives, mostly in great comfort).

We are not on the brink of becoming a police state or an ethno-nationalist monoculture; nor are we returning to 1930s isolationism or nineteenth-century protectionism. What ails our society is a loss of solidarity, stemming from the decline of a confident middle class and the ascendancy of an unaccountable, globalized oligarchy—a condition that goes unaddressed while our leaders direct our attention to nightmares. Their end-of-days mentality is worse than irrelevant. Our leaders have become hysterical because the postwar era is ending, and the political wisdom they took for granted is losing its salience.

The consensus forged in the decades after World War II emphasizes deconsolidation, openness, and fluidity. Princeton historian Daniel T. Rodgers refers to the postwar era as an “age of fracture,” an image taken up by Yuval Levin in his perceptive study of our current politics, The Fractured Republic. I prefer to call the last seventy years “the Heraclitean age,” recalling Heraclitus, the pre-Socratic philosopher who said, “All is flux.” For the postwar era has largely affirmed flux as the beneficial, even indispensable, source of economic, cultural, and moral advancement.

The Heraclitean affirmation of openness and fluidity has been the stable center of our political debates for seventy years, not just in the United States but in the West broadly. But now the settled political and cultural convictions of our leaders have become decadent. Liberals press for ever greater cultural openness—and we are frustrated by politically correct policing, set further adrift in a deregulated culture, and undermined in our already frayed solidarity. Conservatives give the Heraclitean consensus a different inflection, emphasizing economic deregulation—in a society already transformed, and often damaged, by globalization.

This historically conditioned consensus is dying, not our tolerant culture and commitment to freedom. A set of political priorities unique to the postwar era is in crisis, not our constitutional system and liberal democratic norms.

The symbolic beginning of our Heraclitean age was the Supreme Court’s decision in the 1943 case West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette. Three years earlier, after a decadelong struggle against economic depression and on the eve of a global war, the Supreme Court had decided Minersville School District v. Gobitis, ruling that the children of Jehovah’s Witnesses could be forced to pledge allegiance to the flag at the beginning of the school day. That decision reflected the consensus of the time, which was one of consolidation, or as Justice Felix Frankfurter put it, encouraging the “cohesive sentiment,” which he held to be “the ultimate foundation of a free society.”

In the Barnette decision, the Court reversed itself, ruling that children should not be forced to salute the flag and recite the pledge. The majority opinion rejected the use of coercion to achieve social unity. With a totalitarian enemy clearly in view, the majority opinion explicitly warns against nationalism as a danger to be guarded against. As Justice Robert Jackson wrote, “Compulsory unification of opinion achieves only the unanimity of the graveyard.” This swing from worries about insufficient solidarity to the dangers of compelled unity was a harbinger of the consensus to come. The postwar consensus has a center-left and a center-right inflection, but in both instances it gives priority to deconsolidating, deregulating initiatives that loosen the constraints the body politic puts on us.

In the immediate postwar era, the United States remained highly consolidated. Roosevelt’s programs to combat the Great Depression and mobilize for World War II had transformed our economy into a system dominated by large companies that worked closely with government planners. The Cold War encouraged strong affirmations of American patriotism, a consolidating imperative, and the hot war in Korea kept many economic controls in place, justified by the demands of national security. Postwar consolidation was cultural, as well. Mass media came to focus on a narrow range of hit songs and popular TV shows.

In this environment, Supreme Court justices weren’t the only ones worried about the dangers of over-consolidation. As World War II ended, Karl Popper published The Open Society and Its Enemies and Friedrich Hayek The Road to Serfdom. The two authors had different views on politics, but they were united in their anxiety about the threats posed by a superordinate, consolidating Leviathan. Liberal commentators of the 1950s wrote books such as The Lonely Crowd and The Organization Man, lamenting soul-sapping conformism. The 1950s also saw William F. Buckley Jr. contrast collectivism with individualism in God and Man at Yale—an indication of the breadth of the emerging consensus for deconsolidation.

The strongest deconsolidating imperative to emerge in this era was anti-discrimination. We are so thoroughly formed by the postwar consensus that we take this imperative for granted, yet it came to prominence for historical reasons. In the early twentieth century, many elites had regarded the exploitation of the working class as the most pressing assault on human dignity. The relatively stable partnership between labor and capital established by the New Deal made the problem of the exploitation of the working class less urgent. After World War II, the focus shifted to racial discrimination, and by the 1960s, anti-discrimination had become a priority of singular importance. Racism discredited America internationally and gave a propaganda advantage to the Soviet Union. Nonviolent protests put the brutality of racism in the public eye domestically, and riots in Watts and elsewhere threatened to tear the social fabric. These factors shuffled political priorities within America’s leadership class. Ending racial discrimination emerged as a central bipartisan imperative. Soon discrimination against women became a matter of concern as well, and later, discrimination against gays and lesbians. By the last decade of the twentieth century, anti-discrimination had become a dogma. The slightest heterodoxy brings severe condemnation.

Anti-discrimination seeks to break down barriers, remove impediments, and create a more open society. In its classic phase, the civil rights movement fought to remove legal and social barriers that led to discrimination against black Americans in voting, education, housing, and employment. Activists used consciousness-raising to break down the stereotypes and presuppositions that structure our interactions. Similar efforts were made to promote equality between the sexes. Indeed, feminism required even greater cultural deconsolidation, for unlike race, the difference between men and women is assumed by long-standing traditional norms that regulate many areas of life, especially courtship, sex, and the household. These norms had to be made more plastic, if not removed altogether. The imperative of greater fluidity is more obvious still in campaigns for gay rights and transgender rights.

Cultural deregulation came to the fore in the 1960s, driven by the New Left. But the same dynamic has been at work in the postwar American right. Before the rise of the religious right, there were few disagreements between elite Republicans and Democrats about the need to loosen things up. As governor of California, Ronald Reagan signed the nation’s first no-fault divorce law in 1970. Buckley was a proponent of drug legalization. Since 1945, our cultural politics has largely been about what, when, and how much to deconsolidate.

Economic deregulation has enjoyed a similar consensus. Reaganomics was a further stage of a process that had begun when the Truman administration released Detroit from its wartime quotas to return to building cars for consumers. Jimmy Carter authorized the deregulation of airlines and other government-guaranteed cartels. Then came welfare reform, the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, and NAFTA. Over the last generation, most center-right and center-left leaders have agreed that we need to break down barriers, expand choice, and reduce the interference of government in free-market exchanges.

As the last century ended, this consensus hardened into dogma. Just as “diversity” became a buzzword for describing the kind of culture we want, “innovation” became a buzzword for the economy. Both terms connote fluidity, openness, and beneficent change. Left and right have increasingly united around the ideal of a “borderless world,” with the left seeing this ideal in cultural terms and the right in economic terms. But even that distinction gets blurred. Addressing the United Nations after the fall of the Berlin Wall, George H. W. Bush envisioned “a world of open borders, open trade, and, most importantly, open minds.” Today, both the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal reflect this globalist outlook, one in which the formerly closed and consolidated nations of the world evolve toward fluidity and inclusivity.

Within this Heraclitean consensus, intense political battles have been fought. The American left has tended to emphasize cultural deregulation, and the American right presses for economic deregulation. The left wants less rapid and more narrowly targeted economic deregulation, and the right wants less rapid and more narrowly targeted cultural deregulation. Despite their differences, both sides have assumed, all things considered, that flux is best. Our culture should become more welcoming and inclusive; our economy needs to be more innovative and dynamic. Most of us feel the power of the consensus. These affirmations seem normal, natural, and right.

A healthy society develops and sustains a deep consensus, one that stabilizes struggles for political power. So it is not surprising that the boni, the good people, affirm the Heraclitean consensus and its combination of cultural and economic openness. In this consensus, radical libertarians are considered clubbable. Nobody worries about Internet threads in which Silicon Valley software engineers speculate about how to found an anarchist community on a private island. Yale economics professor Robert Shiller can explain why national borders violate the proper universality of moral duty. Radical multiculturalists are also acceptable. The ultra-establishment Ford Foundation funds activists—the cultural mirror images of Shiller—who argue that traditional moral boundaries suppress diversity.

Our universities favor the left, but that’s not decisive. Far more important is the fact that they are establishment institutions dominated by the Heraclitean consensus. Deregulatory conservatism may not be warmly welcomed by liberals who control the universities, but it is not anathematized. Meanwhile, positions that contradict the Heraclitean consensus are denounced as profound threats to human decency. To speak against “diversity,” “inclusion,” and “openness” gets you in trouble. It’s quite simply impossible to get a job in mainstream academia if you are known to hold the view that sodomy is a sin.

It is inconvenient for today’s establishment to face the contradiction that they must exclude those who are not advocates of inclusion. But we make a mistake if we imagine this contradiction to be a serious flaw. A social consensus is not a political philosophy. It seeks to establish all-things-considered priorities, not first principles. The Heraclitean consensus has always admitted of exceptions. We need openness and diversity—except when we don’t. The inconsistencies in the postwar consensus were always there. The problem is that the consensus isn’t working well. What made sense in 1965 and 1980 no longer does. Efforts to create still greater openness and dynamism now undermine the common good.

The bipartisan project of opening up our economy so that companies and investors can operate globally has eroded the American middle class and exacerbated a social divide. Well-educated urban workers flourish, while middle Americans with middling skills lose out. This divide characterizes most of the West. A more open global economy, less constrained by borders, has led to dramatic increases in wealth for tens of millions in the developing world. It has brought tremendous rewards to the top 1 or 2 percent in the developed world, some of which trickle down to the professional classes. But by many measures, middle-income workers in the West have seen little benefit, aside from cheaper consumer goods. This growing disparity has eroded our solidarity.

A cultural chasm compounds the economic one. Charles Murray has documented shocking differences in rates of divorce, illegitimate births, churchgoing, civic involvement, labor participation, and other indicators of flourishing. Well-to-do and well-educated Americans manage reasonably well in our deregulated culture, while those at the bottom of the social scale increasingly live dysfunctional lives in dysfunctional communities. As data analyses by Anne Case and Angus Deaton show, white males with a high school diploma or less education are significantly more likely to die of drug overdose, suicide, or alcohol-related disease than those with four-year college degrees or more. The problems of working-class dysfunction and diminished solidarity were encouraged by the postwar consensus that has favored economic deregulation and cultural deregulation.

The main elements of the postwar consensus were not in themselves wrongheaded. Economic deregulation was a fitting imperative some decades ago. The same can be said for anti-discrimination and its efforts to deregulate culture. These efforts remain useful. We should continue to repeal bad regulations and work against unjust discrimination. But a political consensus establishes priorities, and the priorities of the postwar consensus are out of sync with present realities. Today, our problems almost all flow from too much flux and too little fixity.

For this reason, the preoccupations of liberal and conservative establishments are no longer plausible. Their blindness to reality now destabilizes our political culture. An atmosphere of unreality obtains when newspapers preoccupy themselves with stories about female representation in C-suites—as if the great social problem our society faces is whether already very rich women can get even richer.

Donald Trump is unlikely to provide adept leadership. But I doubt he will end up among our forgettable presidents, the Chester Arthur of the early twenty-first century. My wager is that we will remember Trump as a politically and culturally significant figure. He has exposed the fact that the Heraclitean consensus is breaking down and something new is emerging in our public life. He was the first consequential presidential candidate since George Wallace to run against the postwar consensus—and he won. This does not suggest that America is more racist and more economically populist than it was in 1968. Those who think so are out of touch. Trump’s electoral success was based on a growing popular rejection of Heraclitean priorities. There seems to be an inchoate desire among American voters for something different, something that renews stability and restores solidarity to economic and civic life.

This is broadly evident. Calls for trigger warnings and safe spaces, as well as denunciations of cultural appropriation, express a desire for security, repose, and an inheritance that cannot be taken away from us. Something similar is at work in white nationalism, which likewise seeks to recover a “safe space” and protect a heritage from appropriation. This odd convergence of extremes indicates that our main problems are not rigidity, over-consolidation, and a lack of openness. 2018 is not 1958. We are afflicted by insecurity, fears of homelessness, and the suspicion that we have nothing honorable to pass on to our children. These afflictions, fears, and suspicions give rise to perverse positions and movements on the extremes of public life.

Not a month goes by without the publication of an article warning about the rise of “illiberalism” or a book telling us how to resist the new fascism. But our liberal traditions are not failing. Democracy is not being overthrown. The main features of our market-based economy remain unquestioned by all but a few on the margins. Our disorientation has a more proximate cause.

Our elites are half-aware of truths that are too painful to admit. As the data pile up, can a serious conservative avoid the thought that free-market platitudes now serve the interests of technology monopolies like Google far more than aspiring entrepreneurs in Michigan? Surely the furor on some university campuses makes a serious liberal worry that multiculturalism has gone too far. And the same liberal must know that the Southern Poverty Law Center’s cynical use of its legacy shows how decadent the anti-racism imperative has become.

These suspicions implicate us, for we are among the boni, the “indispensables,” those who articulate and enforce the postwar consensus. As it is failing, we are failing. As it falls, we fall. This explains the anxiety, even hysteria, so evident among once sober-minded people who regard themselves as guardians of responsible politics and civic decency. The hysteria seeks to reinvigorate the Heraclitean consensus by conjuring old threats. Members of cultural and political establishments throughout the West want to believe the 1930s are returning. If this were true, it would vindicate our ongoing loyalty to openness, fluidity, and other motifs of deconsolidation. But we are not living in 1938. The Women’s March last winter was, in the strict sense of the term, conservative. It was organized not to advance any particular cause, but to defend the Heraclitean consensus. The puerile hats and vulgar language evoked an aging generation’s belief in the power of transgression to shatter limits and expand boundaries.

The rhetoric of crisis and calls for resistance emanate from the top of society, especially the center-left establishment that has set the cultural tone for the last seventy years, not from the middle or bottom of society. This is another sign that the ruling consensus is in trouble, not our fundamental institutions or norms.

We cannot continue to preach Heraclitus. The economic and social realities of our time call for a new consensus, one oriented to solidarity. This does not mean turning our backs on the achievements of the postwar era, which are substantial and should be cherished. Our more inclusive social consensus is a gain. Our more dynamic economy is worth celebrating. But in public life, successes often bring new problems. This is our situation. The time has come to shore up the symbols and institutions that unite us. This means relaxing the grip of Heraclitus on our political and cultural imaginations.

Outrage, denunciation, and warnings about impending political disaster have been constant for nearly two years, in an impressive display of bipartisan unity. But that unity within the ruling class has been shown to be politically impotent, and its impotence foretells the arrival of a new consensus. My wager is that it will be one that does justice to truths taught by Parmenides, who argued that permanence and changelessness undergird reality. To lash a society too closely to what is unchanging makes it rigid, unwelcoming, and unproductive. But to become unmoored makes us atomized, homeless, and insecure.

Whatever one thinks about particular candidates or policies, we as religious people should now welcome the end of the postwar era. In its present, decadent phase, the Heraclitean consensus erodes all claims of permanence. It redescribes the objectivity of moral truth as a source of discrimination and an enemy of human flourishing. To be “judgmental” is to sin against openness.

This consensus debilitates our religious communities from within, as well. The Heraclitean consensus has eroded biblical authority and doctrinal stability. As Matthew Rose has recounted, the Death of God theologians presented the Heraclitean renunciation of all lasting power, authority, and existence as the fulfillment, not the negation, of the gospel. Others have been less metaphysically ambitious, but the general tendency in the churches has been to sell doctrinal flexibility and moral “openness” as a fitting way to update Christianity for the modern age.

Let us seek our way forward with open eyes. The postwar consensus was formed to address real problems—yesterday’s problems. Now we must shore up what remains of lasting loyalty, trustworthy solidarity, and things that are solid and enduring. At the end of the age of Heraclitus, we need to recover the wisdom of Parmenides.

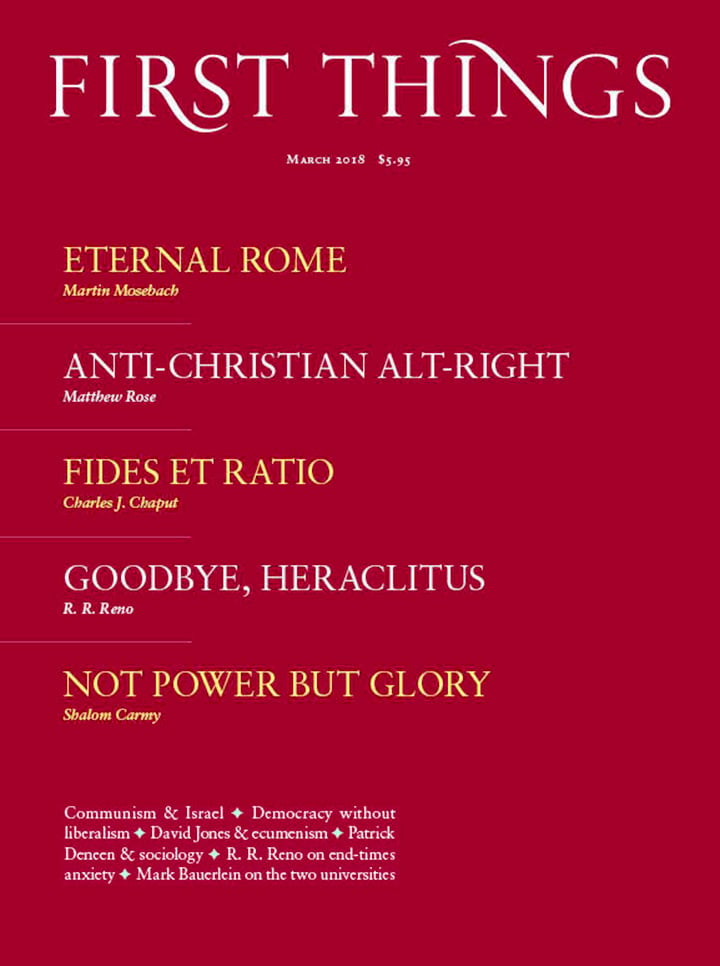

R. R. Reno is editor of First Things.

Follow the conversation on this article in the Letters section of our May 2018 issue.

Nuns Don’t Want to Be Priests

Sixty-four percent of American Catholics say the Church should allow women to be ordained as priests, according…

Christmas Nationalism

Writing for UnHerd, Felix Pope reported on a December 13 Christmas celebration organized by the English nationalist…

An Anglican in the Dominican House

At 9 p.m., when most of the world is preparing for bed, a sea of white habits…