In the early 1880s, Henry James set out to write “a very American tale.” The result was The Bostonians, serialized in a magazine in 1885 and then published in a single volume in 1886. The novel features activist meetings, conversations sprinkled with references to the cause of women’s suffrage, and long digressions in which the narrator canvases litanies of feminist convictions. And yet, as a female critic complained in an early review, The Bostonians does not actually concern itself with the political question of women’s rights in any serious way. This critic was right. In the novel, urgent expressions of early feminism spin round and round in repetitious reiterations, exhausting the reader rather than advancing the narrative.

This inert political atmosphere fits James’s outlook on life. In his letters, he often complained about politics. He resented the way in which election seasons tend to monopolize attention. Otherwise witty, entertaining conversation turns into tense, sometimes bitter political disagreements. During one of the crises that punctuated late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century English political life, James wrote to a friend in despair of the power of political partisanship to eclipse all else: “Literature, art, conversation, society—everything lies dead under its black shadow.” He was not someone who liked talking politics, which is no doubt why the long passages in the novel in which various characters declaim their political convictions are so empty of warmth and interest.

It was that black shadow to which James wished to give fictional form in The Bostonians. His story draws attention to the universalizing, abstracting, and depersonalizing political imagination of New England progressivism, a sensibility that he feared (rightly) would come to dominate the modern era. But James wants to do more than observe and depict. He also wants to resist—resist the imperial ambitions of political ideology. The Bostonians provides a powerful and poignant literary defense of love’s privacy against the progressive’s demand that every sphere of life be subdued by justice’s demands. It is as if James anticipated the feminist battle cry—“the personal is the political”—and wrote a novel to forestall its triumph.

The novel opens in a fashionable Boston neighborhood in the years following the Civil War. Basil Ransom, a young Southerner, has left his defeated homeland to seek opportunity and advancement as a lawyer in New York. In Boston on business, he pays a social call to his young, well-situated Northern cousin, Olive Chancellor. In these initial pages, James teases his reader with the possibility that the impoverished Ransom will marry his rich relative. But their inevitable clash comes quickly. Basil Ransom is a patriarchal Southern conservative, while Olive Chancellor embodies a Northern progressivism committed to reordering society to ensure women’s liberation.

The novel revolves around the increasingly bitter conflict between these two main characters. We learn that Ransom thinks it wrong for women to concern themselves with public affairs, because it coarsens their feminine natures. The hard task of governing a sometimes violent, often unjust world belongs to men, who can endure its trials because of their intrinsically cruder and thicker-skinned natures. Olive, by contrast, has given her heart and soul to the liberation of women, a cause made all the more urgent in her mind by a richly elaborated picture of the long and cruel yoke of male domination that has afflicted women throughout the ages.

At first, James presents Olive as inwardly impoverished by her political zealotry, so consumed with her cause and overwrought with indignation at injustice that her capacity for ordinary human relations has atrophied. When Ransom first meets his cousin, he sees her as “a signal old maid.” In his judgment, “Olive Chancellor was unmarried by every implication of her being. She was a spinster as Shelley was a lyric poet, or as the month of August is sultry.” A certain selfishness is at work in her concern for others. Guilty about her own wealth, she “had long been preoccupied with the romance of the people. She had an immense desire to know intimately some very poor girl.”

And so, in the earliest stages of the novel, it is easy to imagine James wishes us to see Olive as a type: a narrowly focused philanthropist without a heart, a social reformer who sees others primarily through the prism of her own moral needs. But she is more than a type. On his first visit, Ransom is left alone for a moment in her parlor room. He is taken by the domestic perfection Olive has created. “He had never felt himself in the presence of so much organised privacy or of so many objects that spoke of habits and tastes.”

“Habits and tastes” are praise-words in the Jamesian literary universe. He took furnishings seriously. Oil paintings, thick carpets, polished side tables, upholstered chairs, shelves of leather-bound books, and the other elaborated decorations of domestic life were, for him, the material form of soul-enlarging culture. In the case of Olive’s bourgeois Boston home, the tables and sofas and books carefully arranged in brackets (“as if a book were a statuette,” James writes), along with the framed photographs and watercolors, convey domestic solidity and seriousness. Olive may be devoted to the transformation of public culture, but her rooms are primarily dedicated to the ease and beauty of private life.

This is not an insignificant feature of Olive’s personality. She invites Ransom to accompany her to an evening meeting at the home of Miss Birdseye, a local legend who has devoted her life to good causes. The old philanthropist is much admired by Olive. In the literary logic of the novel, the kindly, featureless old woman can be read as Olive’s future, a woman whose personality has been bleached out by progressive commitments. Taking up the theme of interior decoration, James emphasizes this implicit prophecy. The parlor room in Miss Birdseye’s house “was shaped exactly like Miss Chancellor’s.”

A sudden, clashing counterstroke comes immediately, and it reveals James’s larger interest. Unlike Olive, Miss Birdseye gives no attention to her surroundings. The room is “white and featureless,” and its effect on Olive is painful. She “mortally disliked it,” feeling the shabby, ill-considered surroundings an “injury of her taste.” She worships Miss Birdseye and wishes to imitate her singular commitment to social justice, but wonders “whether an absence of nice arrangements were a necessary part of the enthusiasm of humanity.”

Of itself, this droll aside about Olive’s reaction seems to conjure a familiar image of the progressive personality: the hypocritical mentality of the limousine liberal, someone devoted to the great cause of “the people,” but keen to hold on to all the fine things of elite society. But this is a misreading. James never criticizes Olive’s desire for the “nice arrangements.” Gentility in manner of life is always something prized in the novels of Henry James. He affirms Olive’s dislike of the domestic shabbiness of Miss Birdseye’s home and turns his attention to the way in which Olive’s admirable domestic instincts clash with the spiritual implications of her progressive political commitments.

To do so, James introduces a third main character, Verena Tarrant—the personal, domestic focal point of the political conflict between Basil Ransom and Olive Chancellor. At Miss Birdseye’s house, the beautiful young lady appears “like a naiad rising from the waves.” Her father is a “mesmeric healer” who has spent his life on the fringes of respectable New England radicalism. His sensitive young daughter has absorbed his ways of talking. On this occasion, she closes her eyes as her father lays his hands on her head to consecrate her to the task of speaking heartfelt truths. She then stands and speaks warmly about the cause of women. The effect on the gathered room of proper Bostonians with forward-looking views is dramatic. Her almost childlike innocence and sincerity infuse feminist slogans with warmth and immediacy.

Olive is bewitched. She sees Verena as that “very poor girl” who will satisfy her moral need for solidarity with oppressed women. Verena’s remarkable ability to move people with her public speech makes her a perfect apprentice for Olive, who can educate her to serve the great cause of women’s rights. More than progressive politics animates Olive, however. She is possessed by a deep sense “that she had found here what she had been looking for so long—a friend of her own sex with whom she might have a union of soul.” Being a determined (and rich) Bostonian, Olive soon finds a way to befriend Verena, and then quickly secures the permanent residence of the young prodigy in her own home as her singular, intimate companion.

No passage in The Bostonians remotely suggests a lesbian relationship. It was not as though James was unaware of the possibility. After his parents died in the early 1880s, his sister, Alice James, entered into an extended relationship with Katharine Loring, a “New England marriage” as it was called in those days. But James was, I think, largely uninterested in the specifically sexual dimension of personal intimacy. In The Bostonians we read him warmly describing the stable permanence and domestic fullness of Olive and Verena’s life together, not excited moments of sexual encounter, or even discreet ones such as we find in some of James’s other novels. “Will you be my friend,” Olive asks, “my friend of friends, beyond every one, everything, for ever and ever?”

Midway through the novel, Olive comes very close to requiring Verena to promise that she will never marry, a promise Verena testifies that she is willing to make. The two women hover on the edge of ersatz marriage vows, and this narrative device allows James to show that Olive, the young Boston activist, is not like Miss Birdseye at all. She will not sacrifice all her personal needs and desires to the great causes of humanity. She will not commit herself to a sterile public existence shorn of the private joys of domestic life. For all her feminist denigrations of romance and marriage as the preeminent tools of male oppression, Olive ends up throwing herself into the role of “husband” to Verena, her desired “wife.”

As she enters more fully into this domestic role, Olive’s antagonism toward Basil Ransom becomes more acute—precisely because Olive seems, paradoxically, to confirm Ransom’s belief that the husband’s job is to protect his wife, not just from physical danger, but from moral degradation. Olive is keen to lift Verena out of the low circumstances of her family, wishing to rescue her “from the danger of vulgar exploitation.” According to Ransom’s patriarchal view, the husband must exercise authority—and Olive takes charge of Verena’s education, guiding her development with a firm hand. In Ransom’s view, the cruder, thicker-skinned masculine personality should endure the harsh realities of the world outside the home. Olive steels herself to deal with Verena’s father, enduring distasteful financial negotiations (which Olive feels acutely) and paying him a large sum to “leave us alone.”

As Olive becomes more masculine in her domestic role, what began as an ideological conflict with Ransom becomes personal, for the handsome Southerner falls in love with Verena. His desire now rivals Olive’s: “He wanted to take possession of Verena.” Olive senses the threat, and reacts by drawing Verena closer still. She becomes a paragon of male domination: “The fine web of authority, of dependence, that [Verena’s] strenuous companion had woven about her, was now as dense as a suit of golden mail.” Thus James’s literary genius. He has shifted gears. What began as a political novel in the simplistic sense of an ideological conflict becomes far more interesting and timeless. The issue is no longer women’s rights, or their denial. The rest of the action in the novel turns on a universal need for love—and the way in which the modern political imagination works against that need.

For a time, Ransom becomes, paradoxically, the modern ideologue just as Olive has become the traditional patriarch who protects domestic happiness. In long set pieces, James depicts Ransom’s explications of conservative social philosophy, and does so with as much satiric exaggeration as he has given to Olive’s perverse preoccupations with the long history of female subjugation. Ransom hyperventilates about the evils of modern democracy and the feminization of modern man. He is “an immense admirer of the late Thomas Carlyle,” a quite modern and radical figure in his own way, as James recognized. It would seem, therefore, that the Southern patriarch is less a conservative than a reactionary. Ransom makes grand judgments about history, culture, and morality, as did Carlyle, rather than expressing loyalty to the distinctive texture of inherited ways of life.

Ransom’s ideological bent is not innocent. His mother and sisters have a precarious existence in the postbellum poverty of Mississippi. Ransom’s law practice limps along, and he does nothing to help them. His living situation in New York lacks any domestic charm. His stagnation is owing, at least in part, to his dreamy sensibilities and fantasies of making a name for himself by writing articles expounding Carlylean ideas. Ransom’s speculative cast of mind leads him to spend days reading Tocqueville rather than toiling over legal matters, even though he recognizes that such a mentality “would probably not contribute any more to his prosperity in Mississippi than in New York.”

In one scene, Ransom entertains the thought of marrying Olive’s older sister, a frivolous woman whom he does not like, but who would provide him with the financial basis for a career as a public intellectual. Driven by a desire to give his life over to reactionary political crusades, even to the point of prostituting domestic life to his political philosophy, Ransom recapitulates Olive’s hypocrisy. He espouses urgent ideas about masculine responsibility while failing to live up to them, just as she rails against patriarchal patterns of family life while replicating them in her relationship with Verena.

The way in which, at the novel’s midpoint, Olive and Ransom mirror each other as ideologues is not accidental. It allows James to bring into focus the question that interests him. Olive and Ransom both want Verena’s heart. In that contest, the contents of the two political philosophies that clash so bluntly (and uninterestingly) throughout The Bostonians are beside the point. Instead, as the narrative moves forward, James brings to the fore his forebodings about the trajectory of the American political imagination: Olive’s progressive mentality narrows the possibilities of love.

Olive faces a decision. She has brought Verena to New York for a special evening at the home of Mrs. Burrage, a wealthy New Yorker keen to put Verena forward as a representative of the great cause of women. Mrs. Burrage is also eager for her son to woo Verena and make her his wife. By way of various plot contrivances, James ensures that Ransom and Verena enjoy a sustained, private encounter during the New York visit so that the reactionary conservative can declare his love and state his desire to marry her.

Ransom cannot disabuse Verena of the feminist commitments Olive has inculcated. On the contrary, Verena finds Ransom’s outlook on politics contemptuous and brutal, wondering how it is “that being a conservative could make a person so aggressive and unmerciful.” Nevertheless, Ransom the man rather than Ransom the political theorist transfixes Verena. She does not say yes to his proposal. But a thought enters her mind, the one that interests James and serves as the existential fulcrum for the rest of the novel: that of living life for the sake of love rather than for the great causes of justice.

As James makes clear, Olive’s possession of Verena is absolute. Ransom cannot succeed on his own. The future of the women’s friendship depends upon Olive’s choices. Which dream is most dear to this New England progressive: the public goal of women’s rights or the private happiness of domestic repose?

James constructs the narrative in such a way that Olive must answer this question. Before Verena is set to address Mrs. Burrage’s circle of influential friends, the wealthy woman summons Olive to meet with her in private to make a practical proposal. Verena should marry her amiable son, thus obtaining the social status and great wealth necessary to secure Verena’s career as a leading voice for women’s rights. Mrs. Burrage is a white knight. She offers a compliant husband who will play the “female” role of supporting spouse to Verena’s “male” future as a great public figure in the world-historical movement of women’s suffrage. As Mrs. Burrage points out, a sympathetic husband will make Verena “safer.” After marrying, Verena will be removed from the unpredictable world of love where she might be “prey to adventurers, to exploiters, or to people who, once they have hold of her, would shut her up altogether.”

“That was what Olive wanted,” James reports, or so at least she has told herself. But instead of assenting, Olive abruptly leaves. She will not surrender Verena to Mrs. Burrage and her son. The reason is clear. She believes, in her own way, what Ransom preaches. She prizes her domestic dreams of life with Verena more highly than great victories for women’s rights. And so the two women leave New York together. Their union has survived the sieges of both Basil Ransom’s pledge of love and Mrs. Burrage’s promise of political triumph for a great cause. As they leave, Olive and Verena are more tightly, more intimately, and more permanently bonded. In the long, extended, and picturesque scenes set on Cape Cod toward the end of the novel, Ransom tries to woo Verena, with no success. She will not leave Olive, and in the penultimate chapter of the story, the couple retreats in a hidden seclusion, far from public view.

But their bond will be broken. Olive foolishly—inevitably, as James seems to suggest—allows her political dreams to regain the upper hand. She takes on Mrs. Burrage’s role, using her own resources to “bring out Miss Tarrant before the general public.” The decision is fatal. Announcements of Verena’s public address in Boston alert Ransom to her whereabouts, allowing him to formulate a plan to reach Verena and conquer her with his love.

The handsome Southerner makes his way to Verena, whom he finds, with Olive, in a small room in the Boston Music Hall where performers prepare to make their entrance on stage. Olive has planned for this moment. In just a few minutes Verena will embark on her public career, adding her charismatic voice to the cause of women’s rights. Olive wants Verena to speak, knowing that Verena will no longer be defined primarily by her role as Olive’s intimate partner. It’s a sacrifice she’s willing to make for the sake of a higher justice.

The increasingly impatient crowd stamps its feet like ancients clamoring for a gladiatorial victim. A voracious public is ready to consume Verena in frenzied celebrity worship, an image James uses to underline his didactic point about the dangerous tension between public crusades and private happiness. Ransom asserts himself as the source of protection: “Not for worlds, not for millions, shall you give yourself to that roaring crowd. Don’t ask me to care for them, or for any one! What do they care for you but to gape and grin and babble? You are mine, you are not theirs.”

Verena grasps Ransom’s hand. Their eyes lock. The roar of the crowd demanding Verena gets louder. Fearing Ransom’s triumph over Verena’s heart, Olive makes a final, desperate plea. She will “give” Verena to Ransom, provided he allows her to speak “just this once.” A single public, political moment is enough—enough for Olive to justify renouncing her love for Verena. She’s willing to become another Miss Birdseye to ensure that Verena speaks.

The plea is in vain. Olive’s renunciation of the priority of her love frees Verena’s heart. James never suggests that Verena comes to agree with Ransom about the role of women in society. But she welcomes his embrace. Enfolded in his arms, her head buried in the hood of her cloak, hidden from public view, she departs with her lover from the hall. As the great world of public affairs recedes, Verena sighs, “Ah, now I am so glad!” James ends, though, by reminding his readers that while private life brings tears of happiness, it also brings those of pain and sadness.

The women’s movement interested James, I think, not because he had any insights into the relative merits of its specific goals, but because it represented so clearly the aggressive, imperial, and all-conquering impulse of modern politics. Olive’s sad fate is meant to remind us that the bright searchlights of modern notions of equality and justice can blind rather than illuminate. The marching armies of modern bureaucrats, therapists, political activists, and other agents of “social justice,” all very well trained and well armed by seemingly irrefutable general principles, trample the gardens of private life.

James did not wish to commend the political views of Basil Ransom, any more than he rejected the enfranchisement of women, their entry into professions, or their participation in public life. The jaundiced tone with which he narrates Ransom’s political pronouncements suggests that James was well aware that the conservative imagination tends toward a complacent acceptance of injustice. Inherited moral and political views are, like humanity, riddled with corruption, and a pious loyalty to established manners and mores can harden into unbending dogmatism. Moreover, James knew that conservatism can acquire its own quite modern, aggressive, world-conquering habits of mind, latching on to cranky, reactionary, and rebarbative theories that exalt power and authority for their own sake. Thomas Carlyle’s writings, one of the sources of Ransom’s ideas, which Verena found so full of pessimism and anger, has those qualities.

Nevertheless, the way in which James orchestrates the final triumph of Basil Ransom points readers toward a deep and important insight. Modern conservatism can be perverted by a temptation to become a counterrevolutionary theory. Joseph de Maistre provides a historical example. It can become sick with resentment and embittered by defeat and loss. Strands of Southern conservatism in America can have these qualities. And, of course, every conservative outlook is tainted by inherited injustices. Despite these flaws and others, however, Ransom’s view of the world is not intrinsically imperial.

The conservative social and political way of thinking seeks to honor the sanctity of the given. It is primarily concerned with giving status to the status quo. It is a defensive posture that hopes to retain and reinforce pre-political realities rather than reform and revolutionize them. It is a form of public engagement more like sentry duty than conquest and invasion. For this reason, even as the conservative cast of mind often fails to address present injustices that admit of remediation, it has room for domestic repose, for private loyalties, for closed doors—for love.

This is the quality of the conservative imagination that appealed to Henry James, as it should appeal to anyone who cares about human flourishing. At a crucial juncture in the novel, when Ransom sees Verena give one of her spontaneous speeches to a parlor room full of sympathetic listeners, he recognizes her ample gifts and sees that her talents suit her for public life. Yet the thought of Verena absorbed into the great cause of women—into any political cause—horrifies him. “She was made for love,” he tells himself.

We are all made for love. Yes, a woman can participate in politics and still give her life to others in love. We’re all called to serve the common good, a vocation consistent with domestic duties and compatible with the cultivation of private happiness for its own sake. But in The Bostonians James warns against the modern, imperial dream of triumphant justice. For it wishes to conquer our souls as it conquers our societies. A generation ago, the new left had a slogan: The personal is the political. That’s exactly what James feared. We can live with injustice. Sadly, it seems to be our fate. But we cannot live without love.

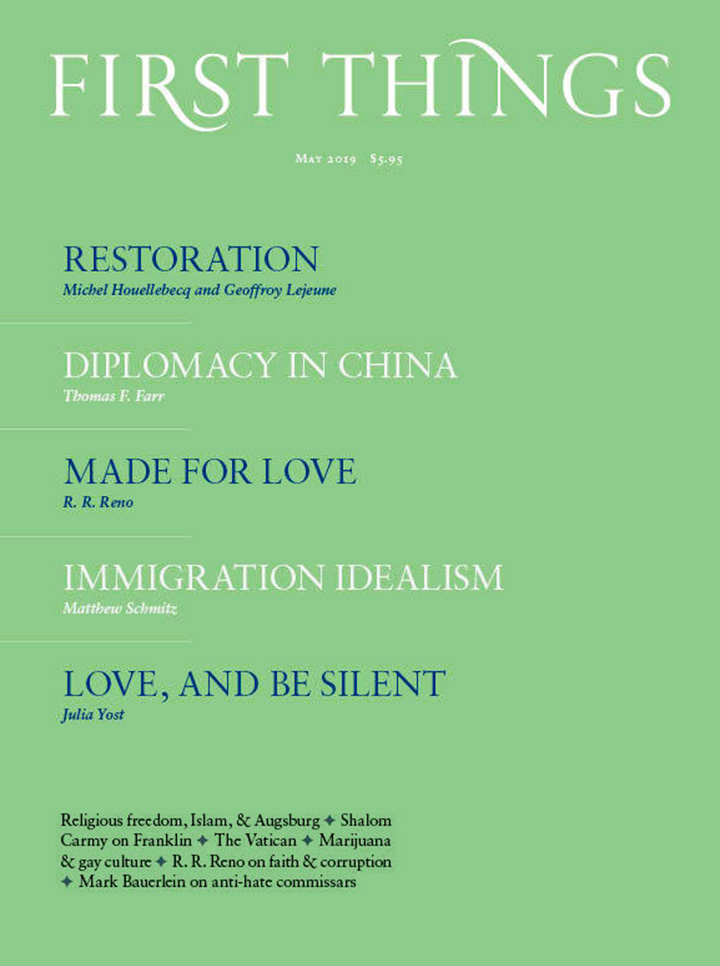

R. R. Reno is editor of First Things.

Photo by Irina via Creative Commons. Image cropped.

Bladee’s Redemptive Rap

Georg Friedrich Philipp von Hardenberg, better known by his pen name Novalis, died at the age of…

Postliberalism and Theology

After my musings about postliberalism went to the press last month (“What Does “Postliberalism” Mean?”, January 2026),…

Nuns Don’t Want to Be Priests

Sixty-four percent of American Catholics say the Church should allow women to be ordained as priests, according…