Proposition #1: The Church is the agent of Christian universalism.

Christianity requires no specific political form. It has adapted to kingdoms, empires, and republics. But Christianity opposes any political project that pretends to a universal mission or dominion. In the Christian view, only the Church can overcome divisions and restore unity to the human race.

Proposition #2: America is a nation, not a church.

Our country has displayed a potent Christian sensibility, which has been crucial to its flourishing. But if we fuse church with nation, there is potential for great mischief. For example, some bishops and pastors judge prudent restrictions on migration to be violations of biblical ideals of universal welcome and hospitality. But those ideals apply to the people of God, the Church, not to the United States.

Before setting out for the New World, John Winthrop drew on the words of Jesus to describe the Puritans’ endeavor as the setting of a shining “city upon a hill.” Winthrop established the conflation of nation with church that has long tempted our country’s influential low-church Protestant tradition. Leavening our commercial republic with the biblical outlook is crucial. Alexis de Tocqueville recognized that religion tempers American individualism. But ascribing the Church’s universal mission to America is perilous. In recent decades it has fueled delusions of an American-led liberal world empire.

We need better theology. Christ came to inaugurate God’s kingdom, not to found the United States of America. Our country is a special place, but it is not a church.

Proposition #3: Every nation is in some sense a “chosen” people.

Abraham Lincoln spoke of Americans as God’s “almost chosen people.” Our mission is not universal salvation; nevertheless, as Lincoln saw, we have an appointed task that fits us to our time and place. We have, in a word, a tradition, a way of life that summons us to sustain it and pass it on to future generations.

An element of “appointment” or “election” characterizes every settled place. In this respect, citizenship is akin to membership in a family. It is a given, not a choice, and certainly not the conclusion to a moral argument. Immigrants who join our nation do so by choice, but within the logic of peoplehood they are in a real sense “sent” to our nation. A people are a people only insofar as they belong both to one another and to the place they inhabit, and that belonging transcends choice. The notion of “naturalization” captures this deep truth.

In a parody of the Christian doctrine of the Incarnation, a distinctly modern mentality promises to bring down universal principles and use them to inaugurate perfect, transparent, and homogeneous justice. This mentality asks by what right the people of America occupy the land and establish its laws. It asks by what right we police our borders.

Whether or not we appeal to the superintending hand of God in public affairs, we must acknowledge the appointed character of our nation. We are “called” to live with one another—again, not by choice, but as a destiny each of us shares. We can speculate about the best political institutions. We can construct ideal societies in our minds. But as Americans we live in accord with the instruments of government forged by men in Philadelphia more than two centuries ago, instruments modified by the twists and turns of our national history. The liberal universalist rebels against this irreducible particularity. A conservative welcomes it as a happy fate; indeed, this spirit of welcome is an essential feature of conservatism. We belong to a tradition. It calls us to cherish what we share, and to perfect it as best we can.

Proposition #4: Biblical universalism affirms nations.

The Bible treats the nation as a fundamental element of the divine plan. The Book of Revelation envisions the peace of the heavenly kingdom populated by people “from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and tongues” (7:9). This echoes the vision of consummation in Isaiah when the people of all the nations will carry the sons and daughters of Israel on their shoulders to Jerusalem (49:22). In Judaism, the nation of Israel is the divine instrument of universalism. In Christianity, that instrument is the Church. Yet both religions see this universalism as a peace of nations, not a peace that transcends nations.

Proposition #5: Modern ideologies seek unbounded empire.

Modern ideologies are comprehensive theories, not particular national traditions. White nationalism is an ideology of this sort. It teaches that the power driving history is in our DNA—not in our political inheritance, which is shaped by history and requires the labor of our devotion to sustain and transmit. By this way of thinking, the genius of America is racial, not constitutional. Our destiny is biological, not political.

Marxism works in the same fashion. The nation is an illusion masking class domination. The future will be made by class power, not by political give-and-take framed by a national tradition. Liberalism, when it ascends to theoretical dominance as an “-ism,” is likewise a universal theory. It seeks a mild but powerful universal empire that both frees us from the constraints of our belonging and provides us with material abundance. It is an empire of liberation and prosperity.

Modern ideologies seek empires unhindered by national traditions. This allows civic life to be more easily reshaped in accord with truths and principles that purport to be universal. Christianity is not opposed to empires, any more than to kingdoms and republics. But it resists the political impulse toward universality. A conservatism that rests on national particularities cannot be derived from theological principles—but it, likewise, resists universality. It regards the political life of the nation as an end in itself. Politics is about politics—the art of living together as people. It is not the mask or instrument of something more universal. Nation-based conservatism, like Christianity, stands against the modern temptation to treat politics as an eschatological enterprise, a struggle to incarnate the universal.

Proposition #6: A mass becomes a people as its members are united in shared loves.

I draw this definition from Augustine, who modified Cicero’s account of civic unity based in shared interests. Both described Rome as a republic, not an empire, one constituted by a shared love of self-government and of honor. These loves characterize the American people, even in our vastness and differences.

The anti-elite, populist sentiments abroad at the moment are best understood as expressions of a love of self-government. Faced with a liberal empire overseen by a technocratic elite, the American people have become truculent. This is true on the left as well as on the right. I am no fan of socialism, but I interpret its rhetorical return as a sign that Democratic voters want to recover their political agency, just as Republican voters did when they ignored their betters and gave the nomination to Donald Trump.

As Americans, we imagine that this love of self-government is common to all nations. But in some places, suspicion and ethnic rivalry make self-government unimaginable—and one cannot love what one cannot imagine. In other places, the populace is docile, satisfied to be governed by elites, hoping only that the laws will be just, or at least not burdensome and humiliating. Don’t tread on me: Americans’ love of self-government is not unique, but it is distinctive. It differentiates us from many other nations in the world, especially in its intensity. The American love of self-government can be a fierce and jealous love.

We are united also in a love of honor. As Tocqueville observed, in our democratic age, all citizens, even those of the lowest estate, have political opinions they are not ashamed to express. We seek a civic culture in which we are recognized as equal partners in our shared way of life, honored by our leaders with the salutation, “My fellow Americans.” In aristocratic nations, honor flows upward. In a democratic people, it reaches downward, lifting up the common man to the dignity of citizenship.

I am frustrated by the lukewarm patriotism of our university-educated elites. Their embarrassment over flag-waving dishonors their fellow citizens. When a man salutes the flag, he is honoring what we share, which is the dignity of citizenship in a great nation. Many of our fellow Americans have accomplished little. Some have made messes of their lives. They have not won prizes, attended fancy universities, achieved celebrity, or accumulated wealth. For them, the honor of shared citizenship is their greatest and most precious source of pride. Elite disdain for patriotic gestures and displays steals from them the glow of this honor. Love will go to great lengths to defend what it loves. For this reason, to the surprise of the “woke,” the American people are angered when the flag and other symbols of our country are dishonored.

We are a partisan people, and always have been. Our cultural roots reach into foreign lands. Some among us came here only recently. Others are descended from those who were brought here in chains. Yet those who think we are a multicultural conglomerate rather than a people are blind to reality. In truth, we are a nation, united by powerful shared loves.

Proposition #7: A nationalist politics can serve the end of Christian universalism.

The First Letter to Timothy warns, “If anyone does not provide for his own people, and especially his own family, he has disowned his faith and is worse than an unbeliever” (5:8). This harsh statement unites a high ideal with a hard fact. The ideal is Christian universalism, which is the peace born of unity in love. The hard fact is that, as fallen creatures, we are in bondage to self-love.

Paternal and maternal bonds can motivate us to sacrifice our own interests for the sake of our children. This makes the family a great school of virtue. But God in his benevolence has provided the nation as a further remedy for our sinful self-regard. The nation is a political community, a way of life in accord with shared loves, not a clan bound by blood. In consequence, patriotic love cures our self-love. In truth, it is a cure more powerful than clan or family ties. To be alive to the national interest means to be, in some sense, dead to self-interest. Mothers and fathers send their sons to war. The most important moral and spiritual function of civic life is to train our loves to reach beyond ourselves, beyond clan and kin, to take in the body politic as a whole.

John Henry Newman once observed, “The love of our private friends is the only preparatory exercise for the love of all men.” Well said, but Newman was too restrictive. The loves we share as Americans—loves that nourish patriotic devotion and encourage the bonds of civic friendship—can prepare our hearts for a higher, more universal love.

Those who dream of a liberal empire imagine justice without virtue and peace without love. Those dreams do not train the hearts of men. Our nation tugs at our hearts, which is why a nationalist orientation orders a polity toward the protection, preservation, and perfection of a way of life. It is a politics of love. This frightens those who want a cool, technocratic regime, and rightly so, for men sacrifice many things, even themselves, for what they love. And this vision troubles the plans of those who aspire to a multicultural regime—again, rightly so, for love unites. I dread the triumph of these loveless visions of our political future, for they mean the end of the democratic age and its supersession by a managerial-therapeutic empire run by central bankers and diversity consultants. But I cannot refute them. I can only say that their purported universalism has nothing to do with Christian universalism. The peace of God that passes all understanding is the peace of love’s devotion.

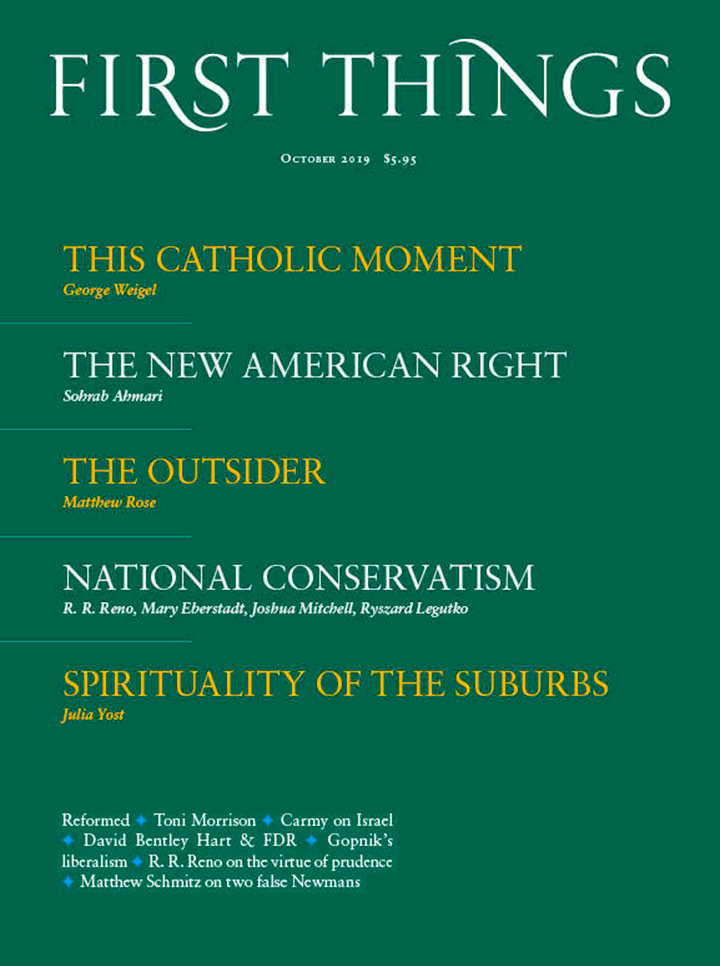

R. R. Reno is editor of First Things. A version of these remarks was delivered at the 2019 National Conservatism Conference in Washington, D.C.

Image by Ahmet Asar via Creative Commons.

Bladee’s Redemptive Rap

Georg Friedrich Philipp von Hardenberg, better known by his pen name Novalis, died at the age of…

Postliberalism and Theology

After my musings about postliberalism went to the press last month (“What Does “Postliberalism” Mean?”, January 2026),…

Nuns Don’t Want to Be Priests

Sixty-four percent of American Catholics say the Church should allow women to be ordained as priests, according…