In 1972, I took part in a Christian panel addressing senior students at a government high school in rural Australia. Afterward, a student approached me to discuss our Catholic claims. He was an unbeliever who was also seeking answers from a small Protestant group. I lost out when I explained that the Catholic Church did not teach that he would go to hell if he refused to become a Catholic. His Protestant sect was quite clear that damnation would follow if they were rejected.

During my recent troubles with the law, this ex-student wrote to console me. He also thanked me for having respected his autonomy. I neither reject nor regret the advice I gave him in 1972. But I do regret that I didn’t convey a greater urgency about the importance of his search and decision.

This student was unusual in thinking of becoming a Catholic, as most traffic has been in the opposite direction. Since the Second Vatican Council, every Western society has seen an exodus of Church members and diminished practice. The Catholic communities in Belgium and Holland, for instance, have almost disappeared.

The “prophets of gloom and doom,” who were explicitly rejected at the Council, have been vindicated, unfortunately and unexpectedly, by a series of brutal reversals across the board. The Four Last Things—heaven and hell, death and judgment—may not be everywhere on the scrapheap, but where they are not rejected they are often ignored or obscured.

Did the threat of hell, a fear of disproportionate punishment after death, have a role in the Church’s decline? Forty or fifty years ago, most parishes in Australia had regular penitents who were plagued by scruples. The scrupulosity caused much suffering, so a reaction against it is not surprising. But is there another side to the coin? Has our silence on reward and punishment after death worsened the indifference by destroying two of our most compelling doctrinal assets?

Everyone wonders whether there is life after death, and most people in history have believed in something like the immortality of the soul.

Naturally, Christian teaching on the last things is more specific. It requires belief in the Creator God, who is rational, good, interested in us, and not capricious. God requires all humans to choose good rather than evil, and faith rather than doubt, indifference, or rejection. The one true God is therefore also the ultimate judge, who separates the sheep from the goats, awarding eternal happiness or punishment on the Last Day, when good and evil souls alike will experience the resurrection of the body. Such a belief can bring immense consolation to grieving family and friends, as any priest who has celebrated funerals for a congregation of believers can attest. But it remains a hard teaching, often fiercely resisted by those who see themselves as autonomous, entitled to define right and wrong for themselves. Neither old-fashioned secularists nor the woke take kindly to the notion of God as both Creator and Judge.

An inevitable question follows for all Christians. How many will be saved? Though Jesus was no sentimentalist, Luke tells us that he did not respond directly to the question of whether only a few would be saved. No percentages are given: “Try your hardest to enter by the narrow door, because I tell you many will try to enter and will not succeed.” Jesus concludes more optimistically that many will come to the feast from every direction, and the last will be first and the first last (Luke 13:22–30).

In Matthew’s account, Jesus is more explicit. The gate is narrow, the road to destruction wide. Trees that do not produce good fruit, vines that produce thorns rather than grapes, will be cut down and burnt, whereas those who listen to Christ’s words and act will build on solid foundations (Matt. 7:12–27).

Matthew also conveys Jesus’s explicit promise that the Son of Man will not be inclusive at the Last Judgment, but will separate the sheep from the goats for eternal reward or eternal punishment. I once wondered why Our Lord was so unsympathetic to goats. I concluded that it was because of their individualism and contrariness, their refusal to cooperate and be herded (Matt. 25:31–46). Goats do not symbolize conversion and community.

Christianity is centered first on love of God and then on love of neighbor (Mark 12:30–31). God loved us so much that his Son died for our redemption (Rom. 5:8). This is the context in which we must place the traditional teachings on heaven and hell.

I have never had a problem with the doctrine that purification might be needed before we can be in God’s presence or cope with his goodness. I have compared it to the discomfort we experience when woken by a sudden bright light. But I have always struggled to reconcile the twin notions of a loving God and eternal punishment.

More than fifty years ago, I was preparing a group of English lads for First Communion. For some reason, they started to explain confidently that hell did not exist. “What about Hitler?” I asked—and hell was back with a vengeance.

So I taught publicly about hell over the decades—once provoking a long letter of support with much profound theologizing from Germain Grisez—but I also expressed the hope, perhaps expectation, that few would be consigned to hell, with the balancing belief that many would need to be purified in purgatory.

I was aware that most theologians, and indeed the Doctors of the Church, believed that the majority of the human race is damned. St. Augustine was quite explicit on the fate of the unbaptized: “Few then are saved in comparison with the many who perish.” He developed his teachings on these points against the Donatists and also Pelagius, who comes across as more reasonable and “modern” on the fate of unbaptized infants. The undergraduate students at my Augustine tutorials, which focused mainly on the Confessions, were almost unanimously indignant about his damnation of unbaptized infants, though he emphasizes that infants experience “the mildest condemnation of all.”

Eight hundred years later, St. Thomas Aquinas’s verdict was likewise clear, but less provocative than Augustine’s. Those who are saved are in the minority, though their number is unknown to us and it is “better to say that to ‘God alone is known the number for whom is reserved eternal happiness.’”

The Council of Trent, in its 1547 Decree on Justification, seems to rule out the possibility that everyone will be saved eventually: “Although ‘He died for all’ (2 Cor. 5:15), not all, however, receive the benefit of His death, but only those to whom the merit of his Passion is communicated.”

But the discussion of the number of those saved was transformed by the teaching of the Second Vatican Council’s Dogmatic Constitution Lumen Gentium, that “those also can attain to salvation who through no fault of their own do not know the Gospel of Christ or his Church, yet sincerely seek God.” The doctrine of “no salvation outside the Church” was thereby substantially developed.

Generations who now enjoyed universal suffrage and were aware of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights readily accepted that neither an accident of birth nor normal human weakness should exclude them from paradise. The inequality presumed by the institution of slavery was now rejected. The Council encouraged dialogue rather than condemnation, persuasion more than punishment, so that the very notion of a death-bearing sin was attenuated. Participation in the sacrament of confession—now called reconciliation—fell dramatically.

I, like many others, came to believe that (nearly) everyone would be saved. I invoked the Alexandrian theologian Origen (circa a.d. 185–254), who taught that at the final apocatastasis all creatures—even the devil—would be saved, and the great contemporary theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar, author of Dare We Hope “That All Men Be Saved”?. But I have come to realize that there is no very great distance between believing that everyone is saved and believing that no one is.

My views changed in an unexpected way. Each year the Vatican authorities run two courses in Rome for “baby bishops,” those recently consecrated. I was chairing a day of discussions when one American bishop developed the claim that our entire priestly activity is determined by how many we believe will be saved. If there is no punishment and all are saved, why then should we bother? Why did Jesus bother with the Cross? I was forced to rethink my position. I returned to Jesus’s teachings in the New Testament and found that they provided insufficient warrant for my optimism. One need not believe with St. Francis Xavier that the unbaptized are damned, but sheltered sentimentalists like me ignore too easily the terrible suffering caused by sin and underestimate the obduracy of the human will.

My late Jesuit friend Fr. Paul Mankowski supported the argument of John Finnis that the failure to take seriously Jesus’s claim to judge everyone on the last day “is at the heart of the crisis of faith and morals.” I now agree. Christian hope for the triumph of the good requires Jesus’s judgment.

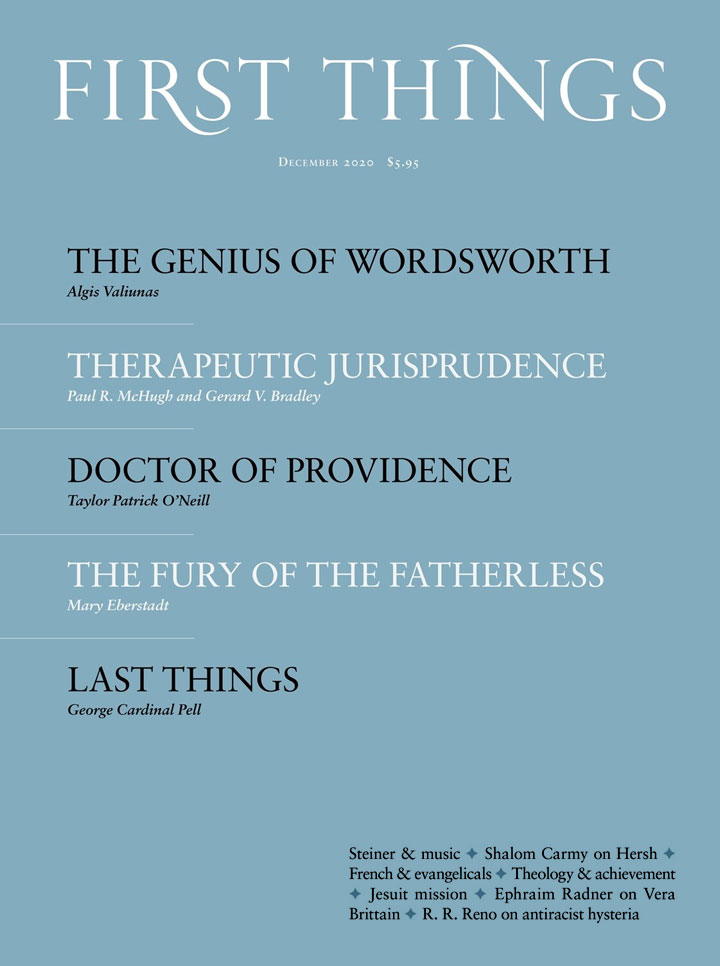

George Cardinal Pell is prefect emeritus of the Vatican Secretariat for the Economy.

Against “God Alone”

A few years ago, I had some routine surgery. Something went wrong in recovery. The nurses on the…

The Scandal of Judaism

Christianity has been marked by hostility toward Jews. I won’t rehearse the history. I’ll simply propose a…

Trump’s Civilizational Project

Secretary of State Marco Rubio spoke at the recent Munich Security Conference. Last year, Vice President JD…