Let me offer a prediction, free of any face-saving hedge: Next year, the Supreme Court will hold that there is no constitutional right to elective abortions. In Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, a case pending before the court, it will return the issue to the states for the first time in forty-nine years. It will do so explicitly, calling out by name, and reversing in full, the two major cases that confected and then entrenched a constitutional right to elective abortion: Roe v. Wade (1973) and Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992). And the vote will be six to three.

Why do I think so? I have no inside information. I know most of the Justices, but I would never ask what they intend to do in a case, and I’m sure none would tell me if I did. But it’s widely thought, and I myself believe, that six of the Justices believe Roe and Casey to be grossly unfaithful to the Constitution and unjust. None will want to entrench those precedents. The question observers debate is whether some of the six might prefer merely to chip away at those precedents. The reasons for this gradualist approach would be to avoid making the Court seem politically motivated and to avoid drawing the Court further into political fights (by, for example, empowering a push for court-packing).

Never mind that Dobbs may be the best chance the Court ever gets to fully reverse Roe and Casey. Forget, too, that it took decades to get a Court like this, years for a case this clean to work its way up the legal system, and nine months for the Court to decide to take it. Apart from all that, a halfway ruling in Dobbs—one that upholds Mississippi’s law but stops short of overruling Roe and Casey—would not avoid politicization. Indeed, it would backfire spectacularly. And it would not be worth the costs. All this follows from four points that are clear to anyone who has spent time with this case and with the broader issue of abortion’s legal status. Hence my prediction.

First: If “politicization” means making the Court seem driven by politics rather than law, Roe and Casey are the ultimate causes of politicization. And having this Court stick by those precedents (when, as seen below, they are squarely at issue) would only heighten the impression that the Court is doing politics, not law. For the public knows that the Court is majority originalist and that originalism cannot be squared with Roe and Casey. So if the Court maintained those precedents against a head-on challenge, no one in the nation would doubt that it had done so for fear of the political fallout. And this signal that the Court is susceptible to political blackmail would only deepen the problem.

Second: Though other cases might have left room to uphold an abortion regulation without fully overruling Roe and Casey or resorting to made-up rationales, this case does not. Any such ruling would have to rest on reasoning that was groundless, vague, or entrenching of some sort of abortion right. It would either exacerbate the Court’s reputation for politicized decision-making, multiply its forays into the political warzone, or extend the damage done to our legal and political order by Roe and Casey’s survival.

Third: Developments this summer make it clear that a failure to overturn Roe and Casey outright would do more than increase those precedents’ immediate harms. It would shatter the conservative legal movement. Scores of filings in Dobbs suggest that the conservative legal movement now sees this case as the ultimate test of this Court’s position on reversing Roe, which is in turn the ultimate test of the Court’s commitment to constitutionalism. Anything less than reversal of Roe would be a wholesale defeat for the conservative legal movement. It would put wind into the sails of critics who have in recent years claimed that the conservative legal establishment is faking a commitment to restoring the courts to principled constitutional reasoning, and is really only interested in securing judgeships for its cronies.

And the disillusionment would be understandable. The Court would have invented a coy and legally groundless half-answer to the most important constitutional question of our time, when that question was squarely presented to the Court and not honestly avoidable. The Justices would have done so against their own professed legal philosophy, in order to placate progressive elites—or out of fear of them. Everyone on the left and right alike would know it.

Fourth: Even if a halfway option in Dobbs could help the Court preserve political capital (as it cannot), doing so would be pointless. The only reason to preserve capital is to spend it on cases in which the rule of law requires a hard decision and the stakes are high. The stakes are nowhere higher than with Roe and Casey, and no two cases are more disruptive of the rule of law. Refusing to spend capital to overturn them would be like refusing to apply to college because the application fee would have to come from your college savings account.

A timid decision in Dobbs would be a grave loss for the rule of law—the most grievous loss since Roe itself. It would shatter the wider movement, built over forty years, for replacing the exercise of raw judicial will with principled constitutional reasoning. It would forfeit the best chance we may ever get to reverse Roe and restore the ability to protect unborn children from lethal violence. Untold numbers of innocents would die in order to bring the howls of outrage at Dobbs a few decibels lower than they would otherwise be.

I find it hard to believe that anyone would take this dismal bargain.

Roe invented a constitutional entitlement to elective abortions effectively at all stages. It forbade virtually all abortion regulations in the first trimester and allowed only those serving the mother’s health—not protecting fetal life—in the second. While it purported to permit prohibitions in the third trimester, it required exceptions for “health,”which a companion case (Doe v. Bolton) defined so broadly as to include “emotional, psychological, [and] familial health” considerations. This guaranteed a virtually unlimited right to abortion up to birth.

The Constitution defines no right to elective abortion, much less one so sweeping. And the precedents cited by Roe—even the most lawless ones—did not come close to supporting a right to any activity so harmful to innocent third parties. Roe leaned instead on lies about the history of our common law and lies about the history of state abortion statutes. It sourced them to two articles by a single writer on legal history, a former general counsel to the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (later known as the National Abortion Rights Action League, and now as NARAL Pro-Choice America). One article was so recent that no actual scholar had been able to examine its sources, and so flawed that it was said to “fudge” the history—by counsel for Jane Roe, who cited it only because, as an internal memorandum put it, it helped “preserve the guise of impartial scholarship while advancing the proper ideological goals.” Once scrutinized, the writer’s sources crumbled, as did Roe’s historical claims, as shown in multiple scholarly refutations.

Indeed, for the next several decades, Roe’s failure as a piece of legal reasoning became a point of near-consensus even in the liberal legal academy. Eminent legal scholar, dean of Stanford Law School, and avowed supporter of legal abortion John Hart Ely wrote that Roe “was not constitutional law and gave almost no appearance of an obligation to try to be.” Harvard’s Laurence Tribe, the preeminent liberal constitutional scholar of his generation, wrote that “behind [Roe’s] own verbal smokescreen, the substantive judgment on which it rests is nowhere to be found.”

And as Edward Lazarus, a former law clerk to Roe’s author, would go on to admit, for decades “no one . . . produced a convincing defense of Roe on its own terms.” So when the Court revisited Roe in Casey, with three new Justices appointed by Republicans, many thought Roe would go. And even when the Court declined to reverse Roe, it could not bring itself to affirm the case wholesale. Embarrassed by Roe’s groundless trimester framework, the pivotal Justices replaced it with a rule barring “undue burdens” on abortion before fetal viability. And even that rule Casey refused to defend by traditional legal arguments or traditional criteria for adhering to precedents.

Instead, Casey declared that the right to have one’s unborn child dismembered or soaked in a saline solution is essential to preserve the “right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life,” because “beliefs about these matters could not define the attributes of personhood were they formed under compulsion of the state.” And Casey explained that it was adhering to Roe because admitting Roe’s mistakes in the face of widespread criticisms would have undermined the Court’s credibility. Thus—bizarrely—did universal recognition of Roe’s bankruptcy become the leading reason to cling to it. In all this, Casey confirmed that the Roe emperor has no clothes, that he never did, that he never will, that he is incapable of keeping a shirt on—and declared that it is for this reason that the procession has got to go on.

Then, to add insult to intellectual and moral injury, the Casey Court ordered the nation to quit its squabbling about abortion already, “call[ing] the contending sides of national controversy to . . . [accept] a common mandate rooted in the Constitution” as read by, well, the Casey Court.

In their legal, moral, and rhetorical enormity, Roe and Casey are rivaled only by Dred Scott v. Sandford (which declared black people incapable of citizenship) and Plessy v. Ferguson (which blessed state-imposed racial segregation). That is the quality of precedent at stake in Dobbs—the precedent some preposterously claim the Court must leave intact to remain credible as an institution of law, not raw politics.

Though the points above are reasons to take any fair opportunity to reverse Roe and Casey, they are consistent with a belief that it’s wisest to reverse Roe and Casey piecemeal, over several cases. But in Dobbs, that incrementalist approach isn’t possible. There is no honest reading of Casey under which the Mississippi law would stand. (That’s because the law prohibits abortions starting well before viability, whereas Casey held that “before viability, the [states’] interests are not strong enough to support a prohibition of abortion.”) So to uphold the Mississippi law, the Court must reverse Casey. And to avoid eliminating any remaining right to abortion, it would need to replace Casey’s doctrine with another. It would need to allow prohibitions to start sometime after conception but before fifteen weeks. Yet the drawing of any such line would find no support in any legal text, history, or precedent, leaving nothing for the Justices to cite in support. An arbitrary line would look—and be—legislative, and hence political. A deliberately vague one, while looking less arbitrary, would invite endless re-litigation of its exact implications. And there’s another problem. As Sherif Girgis summarized it in a widely circulated letter on the obstacles to any of thirteen possible halfway approaches to Dobbs, “to create a new and narrower right, based on a new and more permissive test . . . would require the Justices to justify the new right and test in their own voice, [which] would make it hard for them to say in a future case that there is, after all, no such right. For then they would be rejecting not only Roe and Casey, but their own affirmative reasoning in Dobbs.” So if the Court wanted to make true progress against Roe and Casey without looking political, reversing those precedents would be its only viable option.

If some had hoped for a modest ruling when the Court decided in May to take Dobbs, the ground has shifted beneath them. In July, Mississippi filed a brief dedicated almost entirely to arguing for full reversal of Roe and Casey. That call was then echoed by more than 70 percent of the amicus briefs filed in support of Mississippi (or of neither party), by figures and institutions including half the states, more than half of Congress, hundreds of state lawmakers, hundreds of scholars, and scores of organizations from around the nation. (Indeed, fully one fifth of the briefs—including one that I filed with John Finnis of Oxford—went further, calling on the Court to recognize that the Constitution not only allows but requires states to prohibit elective abortions.) Thus, the conservative legal movement—the movement for constitutionalist judging—has come to see Dobbs as the ultimate test of this Court’s position on a constitutional right to abortion—and the ultimate test of this Court’s (and the conservative legal movement’s) commitment to principled constitutional interpretation.

Against this backdrop, a decision upholding Mississippi’s law without overruling Roe wouldn’t be seen as progress. It would be seen as a betrayal of constitutionalism nearly as acute as outright reaffirmation of Roe. It would signal the decisive failure of an effort of more than forty years to restore constitutionalist judging. It would fracture the conservative legal movement, and shatter along with it any remaining faith in the Chief Justice’s ideal of judges as umpires, calling balls and strikes. The ranks of those expecting judges to advance their political aims would swell—with conservatives.

Roe figures centrally in the judicial “anti-canon”—the cases by which you test the soundness of your theory of constitutional interpretation, and not vice versa. If your theory says Roe was right, so much the worse for your theory. If your movement cannot reverse it, so much the worse for your movement. And if you can’t spend capital to reverse it, then your capital is worthless. So when an opportunity to reverse Roe and Casey is squarely presented, and alternative paths to upholding an abortion law are lawless or would only entrench some right to elective abortion, refusing to reverse Roe and Casey is self-defeating. If it is not obvious that Roe and Casey should now be reversed in full and explicitly, then the conservative legal movement has already failed.

As I write—as you read—unborn children are being slain. As a practical matter, Roe and Casey must be reversed before any of these children can enjoy the full protection of the law. Abortion will not end overnight. Some states will continue to permit the procedure until the Court acknowledges that the unborn possess the right to life. Even women who live in states that prohibit the procedure will be free to cross state lines. But we know that even modest obstacles save lives. The denial of federal funding for elective abortions is estimated to save some sixty thousand unborn children each year. So let us be frank. There is a cost to delay, and that cost comes in innocent lives. That is yet another reason to expect the only defensible outcome: Next year, the Supreme Court will reverse Roe and Casey.

Robert P. George is McCormick Professor of Jurisprudence and director of the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions at Princeton University.

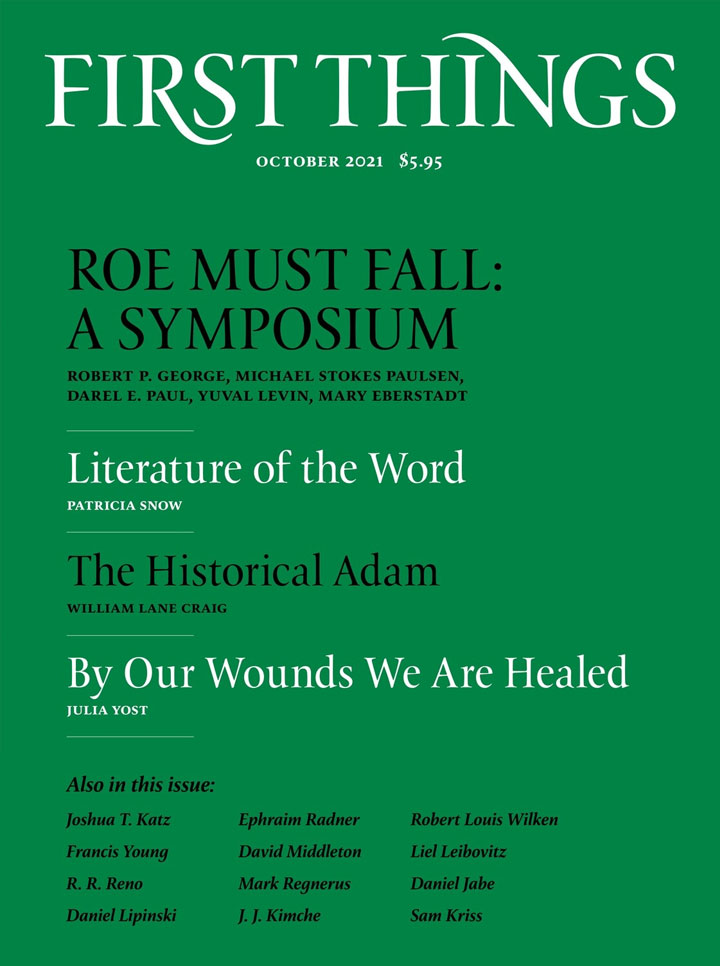

Image by American Life League via Creative Commons. Image cropped.

Back Room to Boardroom

England’s best-groomed town is Darlington, Yorkshire. Data from Britain’s Office of National Statistics show that in 2024,…

Epstein’s Revelations

Far from a mere sordid distraction or an endless supply of tabloid slop, the Epstein files may…

How Kanye Went Nazi

Last year, Kanye West—sometimes known as Ye—released a song titled “Nigga Heil Hitler.” The music video featured…