People talk a lot about polarization. It is true that polling shows a growing partisan divide. But our rancorous political atmosphere is a symptom, not the cause. We are polarized because the credibility of our ruling class has eroded. A trustworthy establishment anchors society and brings stability to public life. Ours has shown itself unworthy of trust, and as a consequence has lost its grip on public sentiment.

Any loss of a stabilizing force at the center of society is disorienting. I recall a conversation I had in 2015 with a prominent figure in the conservative movement. Over lunch he confessed that when it comes to conservative principles he no longer knows what he believes. This wasn’t because his underlying beliefs and loyalties had changed, but because the world around him had. Looking back on the last forty years, he’d concluded that the old conservative consensus from the Reagan and Bush years was no longer working.

Tens of millions of Republican voters have come to the same conclusion. They see failures, not successes. That’s why Donald Trump was able to swat aside the Establishment in 2016 and win the Republican nomination, and then the presidency. It’s why he remains a political force, even after losing in 2020.

Voters on the other side of the aisle are also restless. They rebelled against establishment Democrats in 2016, supporting Bernie Sanders rather than Hillary Clinton. In the 2018 primary, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez kneecapped a high-ranking Democrat in the House of Representatives. The extreme voices on the left have only grown louder and more influential since then. As 2021 draws to a close, there seems no end to the anger and frustration, the over-the-top rhetoric and extreme proposals. The fever gripping public life continues to rise.

Consider a remarkable parallel. Many people on the right have subscribed to QAnon and follow its wild speculations. Many more have become cynical about the power of the “deep state,” which they suspect now controls politics. I can’t put a number on it, but I would not be surprised if more than half of the 74 million people who voted for Trump think our democratic system was rigged against them in some way, which is why Trump’s talk of a stolen election still has traction a year later.

Meanwhile, the New York Times promotes the 1619 Project. Its claims about white privilege and systemic racism add up to an assertion that our system is rigged and our democracy a charade. According to a Gallup poll, 52 percent of young people in the United States profess a positive view of socialism, which I do not read as a thought-out commitment to socialist economic policies, but rather as a vote of no confidence in the status quo.

Whether they manifest it in distrust of vaccines, claims about “the swamp,” convictions about police hostility to blacks, or talk of “socialism,” Americans of all stripes believe that they have been betrayed by “the system.”

The system, of course, is organized and run by a ruling class. This group sets priorities, establishes standards, and heads institutions. Every society needs a ruling class. It gains legitimacy when the many who are governed trust the few who do the governing. Feelings of betrayal undermine this trust. When those feelings become strong enough, the entire system loses legitimacy. Ignorant pundits mindlessly repeat partisan talking points. Cynical media personalities sell advertising by stoking anger and outrage. But these drivers of polarization are epiphenomena. At root, we are experiencing a broad, bipartisan rejection of “responsible” leadership. This rejection explains today’s political turmoil.

We live in a rich and powerful country founded on noble ideals. Why would anyone feel shortchanged? That was pretty much the sentiment expressed in Bill Clinton’s valedictory State of the Union address, delivered in 2000. “Never before,” he exulted, “has our nation enjoyed, at once, so much prosperity and social progress with so little internal crisis and so few external threats.”

Clinton’s cheery self-congratulation expressed a bipartisan, backslapping consensus. (It remains alive in well-insulated elite circles.)With hindsight, we can see that it was almost entirely unmerited. Clinton’s election in 1992 inaugurated Baby Boomer leadership. Sad to say, this generation (of which I’m a trailing member) has careened from disaster to disaster.

Foreign policy. After our victory in the Cold War, the United States enjoyed a position of global dominance not seen since the heyday of the Roman Empire. Over the last thirty years, that dominance has been squandered. Trillions of dollars and thousands of lives were expended on failed wars in the Middle East. Our economic engagement with China was meant to develop that country and bring it into a global system overseen by American power. We now know that this policy was naive and has failed. Today, our largest companies kowtow to the Chinese Communist Party, and our professional sport leagues do Chairman Xi’s bidding.

I recently had lunch with a friend who is the CEO of a midsized financial firm. He told me that I would be shocked to know how many major players on Wall Street are beholden to the Chinese Communist Party. Meanwhile, the tech industry is dependent on China. Hollywood won’t make movies that might run afoul of the priorities of the Chinese government.

Ordinary people do not have expert knowledge about the workings of our globalized economy. But they are not stupid. They can see that the economic interests of those who play leading roles in our country now diverge from their own interests. A fitting word for this divergence is betrayal. After all, it is the first job of a responsible ruling class to keep sources of wealth and power aligned with the needs and concerns of ordinary citizens.

Economic policy. Bill Clinton was born in 1946. Economic data show that his cohort had a more than 80 percent chance of making more money at age thirty than their parents made at the same age. This is the American dream—to do better and get ahead. But something bad happened. After the 1970s, the trend line dipped severely. A person born in 1991 will turn thirty this year. He has a less than 50 percent chance of making more than his parents did at age thirty.

A super-majority of Baby Boomers have done better than their parents, while half of today’s young will do worse than their parents did. This trend does not apply, however, to children of the elite. The last forty years have not been decades of GDP decline. On the contrary, our economy has grown. In 2019 unemployment was at record lows. Entire new industries emerged and produced great wealth. Amazon, Google, and Facebook stand astride the globe. How is it possible that things can be so good while half the country is worse off? Again, the word betrayal comes to the fore.

Cultural policy. Feminism. Gay rights. More immigration. Diversity. Multiculturalism. Tolerance. These words evoke the post-1960s Baby Boomer ambition to make our society less censorious and conformist, more open and inclusive. Boomers have largely achieved these goals. But they have done so at great cost.

In 1960, 8 percent of births were illegitimate. (Notice that I’m supposed to say “out of wedlock,” because “illegitimate” is a judgmental word.) Today, the rate is 40 percent. Liberalization of laws in the 1970s led to dramatic increases in divorce. Today, divorce is somewhat less common, but that’s only because fewer people are getting married in the first place.

Yet, as Charles Murray has documented, the destructive trends in family life do not characterize the upper classes. A neo-traditional ethic holds firm for people at the top, even as they promote the next stages of liberation, which will further disintegrate social norms. Moral deregulation does most of its damage to middle-class and working-class Americans. If your mother has only a high school diploma and you were born in 2021, the odds are against your being raised in an intact home.

A similar class divide can be seen in chronic unemployment, lack of social involvement, and substance abuse. Our leadership class has worked overtime to liberalize attitudes, even to the point of enforcing a punitive political correctness. The well-educated and well-off have the resources and resilience to navigate the new cultural landscape. The less fortunate are shipwrecked.

According to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 100,000 people died from drug overdoses in 2020. It is telling that our policy response to COVID-19 was to shut down the country and spend trillions of dollars to ease the damage. Meanwhile, our policy response to 100,000 dead from drug overdose—an epidemic that has killed nearly a million people since 1999—has been to legalize marijuana.

In 2012, the Republican candidate for president described nearly half the country as “takers.” In 2016, the Democratic candidate relegated half the country to a “basket of deplorables.” These comments were political mistakes. It’s never wise to insult the electorate. But the comments were also revealing.

At this juncture, a bipartisan consensus obtains in our ruling class. The rich and powerful believe that we live in a degraded and broken country filled with dependent and dysfunctional people. It’s interesting to note that angry voters agree. They just differ about whom to blame for the all too real and very deep problems facing our country. And I submit that ordinary people, not the well-credentialed people running things, have the more accurate political philosophy. They see that a country becomes de-industrialized, degraded, and dysfunctional because its ruling class has failed. Put simply: A fish rots from the head down.

Faith’s Crucial Role

Krisis is Greek for “crisis,” a straightforward transliteration. Today, when the word is so frequently used, it’s worth going back to the original meaning in the New Testament. Our Bibles consistently translate krisis as “judgment.” It may also be translated as “turning point.” Both meanings are apt. Today we sense that the old truths aren’t true anymore. We face hard decisions, which will set the agenda for the coming decades, not just in the United States but throughout the West. We can’t just keep kicking the can down the road. Decisions (another word used to translate krisis) must be made.

Our failed ruling class compounds our problems. We can’t look to the “good” and “responsible” people for guidance. How can we trust a foreign policy establishment that squandered so much blood and treasure? How can we trust the billionaires who have prospered from globalization, while ordinary Americans fell behind? How can we trust professors who have concocted gender theory, critical race theory, and other conceptions that set us against not only nature but each other? But I am not without hope. I am convinced that people of faith, unlike many of our secular counterparts, are well positioned to face this crisis.

Why my confidence? During the last forty years it has been very good to be well educated, securely placed, and handsomely compensated. Why wouldn’t our leadership class want to ignore current problems and work overtime to keep the current system in place?

Some people of faith are part of the leadership class. Others of us work for or minister to them. We, too, are often blinded by old truths and captive to self-interest. In the 2000s, I supported the Iraq War. I was naive about China and the effects of globalization. But we are not unmanned. Our faith trains us to face reality.

“Through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault.” Catholics should be grateful for the recent re-translation of the liturgy, which restored a fullness of gravity to the act of contrition. Other religious traditions have similar liturgies of repentance. It is very difficult for a ruling class to admit its failures, though. Successful people are often told how wonderful they are. Expert! Creative! Innovative! Social scientists report declines in life expectancy, a shocking development for a wealthy country like our own, and our ruling class scratches its head for a brief moment, and then moves on. So I put before you this proposition: It will fall to people of faith to lead the way in a much-needed collective examination of conscience.

Another source of my confidence comes from the substance of our traditions. Today’s troubles and turmoil are best described as a crisis of solidarity. Those at the top of society now have economic interests in China and continued globalization, interests not shared by their countrymen. The well-off also benefit from large-scale immigration. It provides cheap labor and lets our leaders ignore the festering dysfunction of native-born Americans at the lower end of the social scale. And the upper echelons have the resources to opt out of failed public schools and our increasingly crude public culture.

Invocations of individual freedom offer little help as we grapple with this crisis. Too often they blind us to the problems we face and legitimate the temptation to opt out. But religious people bring a different tradition into American public life. The solidarity of the synagogue and church is supernatural. God has chosen his people and set them apart from the nations. In Christ, we are brothers and sisters, sharing in his most precious body and blood. This unity leavens our social and political imaginations, allowing us to see the wounds suffered by our fellow citizens—and motivating us to bind them up.

We’re not going to get onto the right path without good political leadership. There’s a very American tradition of suspicion of government. It’s a healthy suspicion. But it can be taken too far. And it can paralyze us. At its worst, this suspicion becomes an excuse not to make a decision. Paralysis and evasion often characterize American conservatives.

Let me put this point directly. Markets are not going to solve the problems created by bad political leadership over the last generation. Nor will cultural renewal. Yes, we need vibrant markets, and we need cultural renewal. But a country’s political future is downstream from its political past. To address our problems, we’re going to need political courage, boldness, and wisdom.

This brings me to my final source of confidence: Our religious traditions, especially Catholicism and Judaism, are not anti-government. We understand the limits of politics. Unlike utopians on the left, we know politics won’t save us. But we recognize its necessity, and more than that, we honor its dignity.

Our leadership class is enamored of technocratic schemes and it believes in the transcendent power of expertise. Too many of us imagine that we can find win-win “solutions” rather than make hard decisions. But the Christian life is nothing like this. Yes, we try to analyze situations accurately. We subject ideas to the testing rigor of debate. But who among us has not faced a crisis—faced a hard personal or professional decision—and turned to God in prayer? We ask him, “Lord, show me the way. Give me courage to say and do what must be said and done.” Only people who have this kind of humility and courage can lead an American renewal.

As I have traveled around our country in recent months, I’ve met many men and women who possess that humility and courage. Not all of them are Catholics, or Christians. Not all are religious. But there is no doubt in my mind that the kinds of people who read First Things have a central role to play. The crisis before us calls for us to judge and act with intelligence and purpose. Let us answer as did the prophets of old, declaring, “Here I am.”

Jesse Reno

The sun was radiant the afternoon my son was buried. The Jewish ceremony is spare, made up of brief prayers, psalms, and the Mourner’s Kaddish—frank, unadorned words spoken to God when words fail. Benumbed beside my wife and daughter, I somehow said what needed to be said. Then, stepping forward, I took up a sharp-pointed shovel, thrust it into the pile of dirt, and cast the first clods onto the simple pine box at the bottom of the freshly dug grave. I handed the shovel to my wife, who did the same, a mother’s final act of worldly comfort and succor for her beloved child.

A few days before, one of Jesse’s friends in Seattle had sent my wife an urgent Facebook message, reporting that he had died in a car accident. Calls to the Montana State Police yielded no confirmation. Searching the web, my wife found a list of accidents on that day, September 29. A fatal crash was recorded in Rosebud County. I called the county sheriff’s office. The receptionist put me through. “I’m Jesse Reno’s father, and I’ve been told he was killed in a car accident in Montana. I’d like to know if this is true.” There was a long pause. Then the sheriff said, his voice only slightly less anguished than mine, “Yes.”

Grief bore down upon my wife and me. In a fog of tears, we bought tickets to fly to Billings, Montana, the next morning. Our son was beyond our protection, beyond our consolation. But it seemed foolish to resist the instinct to go to him in his time of distress. The dead need tending to.

Arriving in the early afternoon on Thursday, we immediately drove east along Interstate 90 and U.S. Route 212 to Lame Deer, Montana, retracing Jesse’s final steps. He was heading to a music festival in Minnesota with a friend, driving through the night. Going to the east, the highway rises out of Lame Deer to cross a high plateau. It was there that the accident occurred, a few hundred yards past mile marker 50.

We spent some time at the crash site, remembering, praying, and gathering small remembrances. Then we drove north to Forsyth, Montana, to the funeral home where his body had been taken.

The funeral director was able to give us some information about the accident. A medical examination shows that Jesse died from head trauma and a broken neck. It is very likely he died instantly. The crash occurred around 5 a.m., shortly after he had turned over the wheel to his travel companion, whom we do not know, but who is part of Jesse’s circle of friends in Seattle. From what we have gathered, she was distracted while driving and lost control. Jesse was wearing a seatbelt, but had reclined his seat, giving him less protection. The driver was injured, but not severely. Apparently, Jesse received the impact in the worst possible way.

After making arrangements for his transport to New York for burial, we viewed Jesse’s body. The injuries were not disfiguring. His countenance was peaceful. The upsurge of grief was very painful for both of us. But we were grateful to have been able to see his sweet face for a final time.

Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted. As we prepared to leave, the funeral director gathered my wife into his arms. “I’m a hugger,” he explained. It was the first of many embraces we were to receive, some painful in their communion of grief, but all welcome and consoling.

We flew back to New York the next day. As the jet engines softly roared, I silently said the rosary. I made an interior dedication of the third decade, the crown of thorns, to mothers who have lost their children. I began the first Hail Mary, and my wife began to cry. She put her head on my chest. As I held her and prayed, God overshadowed our suffering with his mighty hand and outstretched arm. My grief mingled with awe. Greatly to be praised is the name of the Lord. May the Good Shepherd lay our dear son down in green pastures.

WHILE WE’RE AT IT

♦ Northwestern professor Gary Saul Morson is rightly concerned about the growing misuse of science as a weapon in political debates. Writing in the Wall Street Journal (“Partisan Science in America”):

Perhaps the clearest sign that a scientist, or anyone else, is misrepresenting science is a confusion of a science with political or social claims that it is thought to imply. That is what social Darwinists and Soviet dialectical materialists did. Such claims were never scientific. They are a clear sign of pseudoscience. One must argue for or against the social or political implications of a scientific discovery in the same way as for any social or political ideas.

It’s not just social Darwinism and Soviet dialectical materialism that promote pseudoscience. Exhortations to “follow the science” during the pandemic perverted epidemiology by giving the false impression that lockdowns and mask mandates were clear-cut matters of science, when in fact they were necessarily political decisions that involved many social and economic considerations. Morson is not optimistic about the damage done in recent years:

The greater danger to the public’s trust in science comes not from the uneducated but from the politicians and journalists who claim to speak in the name of science. Still more, it comes from scientists themselves, either because of what they say publicly in the name of science or their failure to correct others’ misrepresentations of it.

Although Morson does not mention it, one thinks immediately of today’s gender fantasies and the culpable silence of biologists and other experts in the life sciences.

♦ London Mayor Sadiq Khan used strong words in the summer of 2020: “The brutal killing of George Floyd has rightly ignited fury around the world. I stand in solidarity with black people experiencing systemic racism, and commit to use my voice to amplify theirs.” Last month, Khan was exquisitely circumspect when a Muslim assassinated David Amess while the British Member of Parliament was meeting with his constituents in Leigh-on-Sea. “I am so deeply, deeply saddened by the tragic news that Sir David has passed away. He loved being an MP and was a great public servant. It is just awful.”

“Passed away”? Amess was stabbed multiple times at midday as those waiting to speak with him looked on in horror. A friend from London commented, “Basically no debate here on Islamic terror. Feels like an Islamist could murder the Prime Minister or the Queen and people would just shrug it off and move on.”

♦ Healthcare consultant Kevin Roche writing about Sweden:

People in the country never obsessed over the epidemic and now basically ignore it. Sweden has a high vax rate, but they also aren’t freaking out over whether vaccines work and boosters are needed. The overall CV-19 death rate, and Sweden uses a very liberal attribution method, was 1440 per million, compared to a far higher 1989 in the US. Minnesota is at about 1406. Sweden’s total excess deaths are much lower, as they did not terrorize their citizens into missing needed healthcare or engaging in drug and alcohol abuse resulting in deaths. The country also did far less damage to its economy and its social fabric. Oh, and no one wears masks or is told they have to wear a mask. I know which country I would rather be living in.

Call it a witness to sanity—not a witness of transcendent significance, perhaps, but not without importance in our present moment.

♦ Christianity, like Confucianism, is agnostic about food, allowing great latitude in what we eat. Christians take it for granted, but the lack of dietary regulation is remarkable. As Rémi Brague notes, there are Jewish cuisines and Muslim cuisines, but there are no Christian ways of cooking and eating. In all likelihood, as the West sheds loyalty to Christianity as the normative center of society, we will revert to the norm, categorizing foods in terms of purity and defilement, and regulating diet accordingly. It’s already happening. The new food chains in New York tout their food as pure and virtuous. One features the motto, “Eat Clean.” Many people adopt rigorous dietary regimes such as veganism.

One of the conceits of secularism is that it has put religion in the rearview mirror. Hardly. As we cast off Christianity, public life will not become a neutral zone occupied by libertarian agnostics. Quite the contrary—cultural regulation invested with sacred significance will return. What is clean and what is polluted? The woke revolutionaries apply this question to political views. They are not interested in debate. Rather, they cancel, which is today’s equivalent of driving out impurity and limiting its contagion. I predict a similar approach to food. Currently, we are being disciplined to adopt the latest woke pieties. Soon, we’ll be compelled to conform to progressive dietary laws.

♦ Many contradictions have been softened by euphemisms and happy talk over the last fifty years. One is affirmative action. Another is diversity, which has largely supplanted affirmative action. These terms are meant to turn attention away from quotas, and thus square the circle so that we can continue to believe in the liberal principle that each person is treated as an individual. In this tradition of drawing a veil over reality, the Wall Street Journal recently reported “gains in diversity” on corporate boards. In the last year, one third of newly appointed independent board members for S&P 500 companies were black. But only 13 percent of the population of the United States is black, and blacks are nearly half as likely to earn a bachelor’s degree as are whites and Asians. (They earn MBAs at still lower comparative rates.) In short, in the aftermath of Black Lives Matter, white Baby Boomer corporate leaders have embarked on a massive effort to recruit black corporate board members from a very small pool of candidates. The illiberality is astounding. The dream of an America in which people are judged by the content of their character and level of skill seems more remote than ever.

♦ “Liberal” is a plastic adjective. In the United States, it functions as a synonym for “progressive,” which is likewise a highly mobile, open-ended term. In 2014, George Marsden published The Twilight of the American Enlightenment: The 1950s and the Crisis of Liberal Belief. The book documents the shift from liberalism based on natural right to a post–World War II outlook that emphasized pragmatic management of social tensions. On this view, “liberal” characterizes a person attentive to social problems and supportive of technocratic, “non-ideological” solutions. The postwar liberal was not overly concerned with “principles.” The same holds true today. The liberal can defend free speech—or not, as we’ve seen in recent years. He can insist on merit—until it leads to unwelcome results. He requires everyone to follow procedures—but makes exceptions for those who share his good intentions. I’m not a free speech absolutist, nor do I make a god of merit or procedures. But what passes under the label “liberal” today has become so riddled with incoherence that it is no surprise that the term has become suspect, and those on the left now prefer “progressive.”

♦ After reading last month’s column on safetyism, a subscriber directed me to A Failure of Nerve: Leadership in the Age of the Quick-Fix by Rabbi Edwin Friedman, who writes, “This focus on safety has become so omnipresent in our chronically anxious civilization that there is a real danger that we will come to believe that safety is the most important value in life.” He goes on to say, “If society is to evolve, . . . then safety can never be allowed to become more important than adventure. We are on our way to becoming a nation of ‘skimmers,’ living off the risks of previous generations.” After all, “Everything we enjoy as part of our advanced civilization . . . came about because previous generations made adventure more important than safety.”

♦ The same astute subscriber pointed out that my knowledge of pop culture is lacking. “Two girls for every boy” is not a line from a Beach Boys song, as I claimed last month in this column. It’s from the 1963 song “Surf City,” which, though co-written by Beach Boy Brian Wilson and Jan Berry, was recorded by the latter’s duo, Jan & Dean, who produced a series of Southern California beach-and-hot-rod songs.

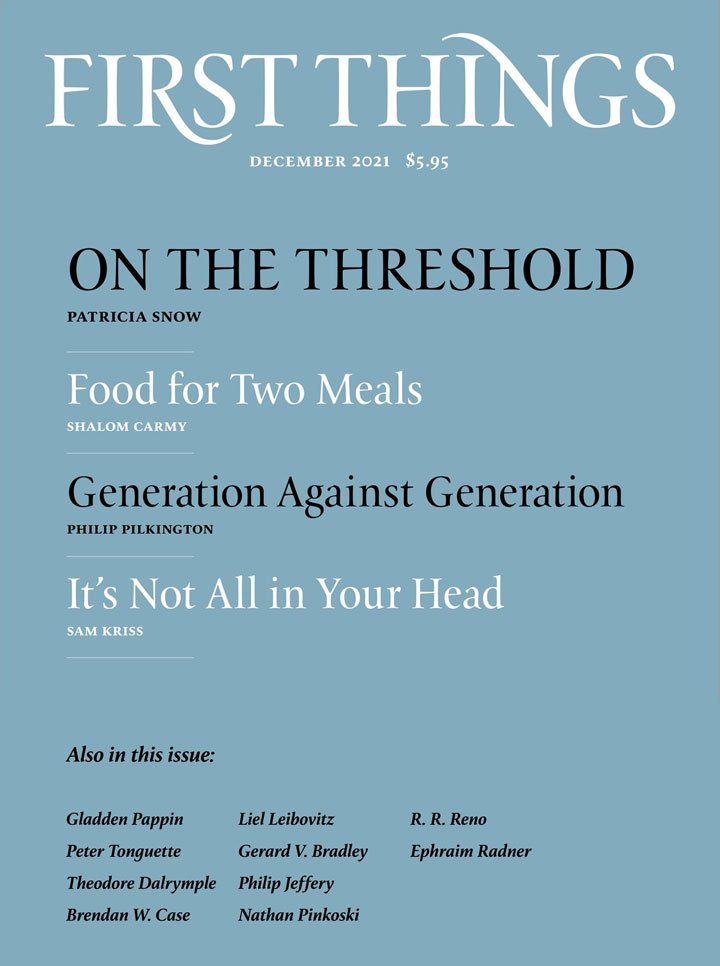

♦ At the end of November, we will launch our year-end fundraising campaign. First Things enjoys a remarkable level of support from its readership. Please donate and help us enter the coming year with a well-stocked war chest. Your generosity ensures that First Things remains a strong voice.

♦ I’m pleased to welcome Dan Hitchens as senior editor. Having written on occasion for the Catholic Herald, where he plied his trade for a number of years, I know from experience that he’s a superb editor. And, of course, readers of this fine magazine have enjoyed his essays and reviews on James McAuley, Thomas Becket, George Orwell, Dorothy Day, and more. He has been laboring for us part time in recent months. It’s great now to have the full measure of his talent.

♦ As I report above, in late September my son died in a car accident. In the last few weeks, as so many readers and friends have extended their condolences, I’ve felt the great blessing of being part of a fellowship that is much more than a publication. The outpouring of prayer and support in the days that followed Jesse’s death was a consolation to my wife and me. Please know that we are deeply grateful.

Jeffrey Epstein’s Critique of Catholicism

At risk of being controversial, I must take issue with Jeffrey Epstein. Buried in the latest tranche…

Bladee’s Redemptive Rap

Georg Friedrich Philipp von Hardenberg, better known by his pen name Novalis, died at the age of…

Postliberalism and Theology

After my musings about postliberalism went to the press last month (“What Does “Postliberalism” Mean?”, January 2026),…