The central commandment found in American etiquette Torah is this old chestnut: Never discuss religion or politics. Do so, and you run the risk of offending those who hold different views. This is a grave sin, because polite society, after all, is an ideal predicated on the polite fiction that people are fragile, quarrels are corrosive, and conflict is best avoided at all costs.

For a long time, Americans, hallelujah, have ignored this fusty and prudish desire to avoid conflict at all costs, at least when it comes to religion. In 2016 the Pew Research Center asked how many people would avoid discussing their faith with folks they knew held very different beliefs: Only 27 percent of respondents said they’d keep quiet rather than risk an argument. Sadly, the spirit of forthrightness has waned. By 2019, that number had gone up to 33 percent, and when the latest survey was released earlier this year, 41 percent of those asked said they’d prefer to keep mum.

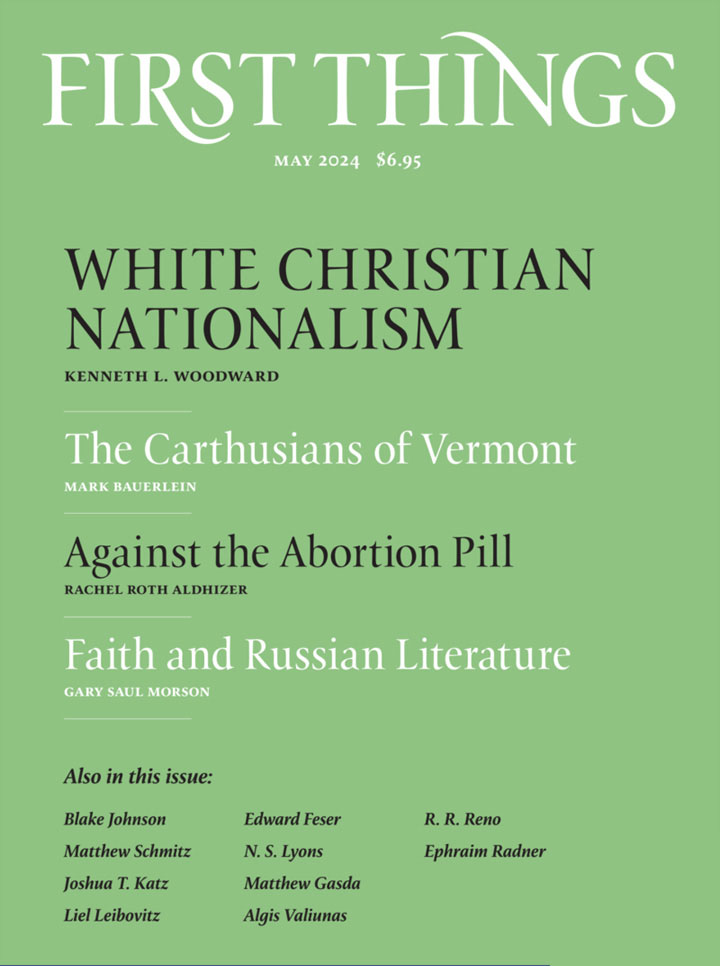

In this trend, we glimpse the darkening of American public life. You hardly need specialized knowledge or advanced degrees to understand why the number of people who are disinclined to talk about God with their fellow Americans has more than doubled over the course of the decade. All you need to do is go to the movies. Rob Reiner, the Hollywood eminence who gave us such beloved classics as The Princess Bride and This Is Spinal Tap, is now peddling God and Country, a documentary that portrays vast swaths of believing Americans as one hood and robe away from full-blown klansmanship. He treats their faith as a thin veneer for white supremacy, a benighted ideology that the film labels “Christian Nationalism.” Or you can leaf through a Ms. magazine and learn that it was “Christian Nationalism” that robbed American women of their reproductive rights and ushered in the new Dark Ages. The same specter haunts the halls of our most esteemed philanthropic institutions as well, which is why the Henry Luce Foundation recently awarded a major university a sizable grant to research and resist—you guessed it—“Christian Nationalism.”

Just what is Christian Nationalism? Its detractors—like the beaver, the banker, the barrister, and the other heroes of Lewis Carroll’s The Hunting of the Snark, who set out to capture a creature they’ve never seen, can’t describe, and aren’t sure even exists—rarely bother with definitions. They are convinced that the term defines itself: To be a Christian is to be a nationalist, a misogynist, a bigot, a creep—all of which is to say, a Christian won’t be a secular progressive, which amounts to the gravest moral failure.

Is it any wonder that Americans, the majority of whom still identify as Christian, aren’t too keen on talking openly about their faith? Who wants to be put into the basket of deplorables?

But religious believers should talk openly, and the more ardent our faith, the more vocal we should be. We should talk about our faith as often and as loudly and as proudly as we can. Why? Two good reasons come to mind.

First, speaking candidly about faith is key to building long-lasting coalitions based not on transient and transactional allyship but on real friendship that can only thrive when we’re being honest with each other. Aristotle said that true friendship requires agreement about the highest good. How can we find true friends if we’re hiding our true beliefs?

I’ve endured two decades’ worth of interfaith breakfasts for Christians and Jews. Very little has been on the menu save for warmed-over platitudes, nothing of real substance. That’s because the organizers, well-meaning as they might have been, wanted to make sure no one would bring up any disagreements about, say, God’s actual designs for man that could injure the pleasantly numbing sensation you get from mouthing slogans like “Judeo-Christian values.” Why make things awkward by mentioning that some of us believe, truly and wholeheartedly, in Jesus Christ as the promised Messiah, while some of us decidedly do not? Better, went the logic, to stick to nondescript, nondenominational, non-confrontational, and non-inspiring prayer. All of this was done in the hope that a lasting sense of kinship would somehow bloom.

It rarely does, because vagueness makes for arid soil.

We don’t need to be “nice” all the time. I recently had the privilege of partaking in an interfaith group facilitated by this marvelous magazine, one that allowed for theological headbutting. The experience was thrilling, and I realized how powerful and moving it can be for men and women of different religious traditions to come together and joyfully talk about their beliefs—not only those they held in common but, more crucially, those they did not.

Hearing my Catholic and Protestant friends talk passionately and unreservedly about what they truly believed about God’s salvific plan didn’t make me fear that a new Torquemada was about to storm in, interrupt our lunch, and send me off in chains. Hearing Christians say very strange things about Jesus fulfilling the sacrificial laws pertaining to Temple worship (from where I sit, it seems a bit of a stretch) didn’t make me nervous or uncomfortable. Instead, it accelerated my own passion for my own Jewish practice. And truth be told, the frank reports of their Christian beliefs made me feel much closer to my Gentile friends. I was struck by the fact that they were so kind and trusting as to open their hearts without reservation in the hope that I’ll understand them and then do the same. That’s the royal road to deep friendship. And we’re not going to have these heart-opening, soul-engaging conversations with each other unless we speak up about our faith.

But there’s a second, even greater reason why we should be vocal about our beliefs. Andrés Manuel López Obrador put it clearly. When speaking about the fentanyl crisis north of his border, Mexico’s populist president had fiery words for his American neighbors. After denying the well-documented fact that Mexican cartels were manufacturing the deadly drug, López Obrador offered up a reason why so many Americans, citizens of the world’s most thriving and admired nation, flock to opioids to dull their pain: “There is a lot of disintegration of families, there is a lot of individualism, there is a lack of love, of brotherhood, of hugs and embraces.” To paraphrase a famous Jewish teacher, instead of hectoring our neighbors to the south, those of us up north need to deal with the beam in our own eye.

Amen, Selah. Opioid overdoses are aptly referred to as deaths of despair, and despair can’t be fixed by science or by the government. Despair calls for hope, a rare resource produced in the hearts of those who believe that life has some purpose beyond mere existence. Put bluntly, if we want to help our fellow Americans curb their addictions to fentanyl and Facebook and the filth peddled by pornographic websites, we need to offer them a vision of a life rich with love and gratitude and meaning, a life of answering to a higher authority, a life dedicated to a higher calling.

We need to stop using the faint, anemic language of our therapeutic culture or the cold technocratic jargon that ices out anything fiery. What our age desperately needs is for religious folks like us to speak about the highest truths with the same urgency of feeling that sweeps over us as we kneel during Mass, or sways us when we pray the Shmoneh Esreh, the central element of Judaism’s thrice-daily prayers. We should obey the old adage taught to cub reporters on day one of journalism school: Show it, don’t tell it. When we meet someone who does not share our religious convictions, we shouldn’t just tell them what we believe; we should bear witness, as the Christians like to say, showing them how happy our faith makes us, how content, and how thankful for our families and our friends and all that we’ve got.

There’s no other way to cure our sick culture. This is a major battle, and it won’t be won in the Supreme Court or in the ballot box. It’ll be won in the supermarket or the elementary school parking lot, in the bleachers watching a Little League game or in the park on a lazy afternoon. It’ll be won by people who buck the “play nice, say nothing” trend and commit to wearing their faith on their sleeve, shining their light for all to see.

This is America. We’re a perpetually teenaged nation, one big junior high cafeteria, and everyone wants to sit with the kids who look like they’re having the most fun. So this is my assignment: We need to take all the energy we generate in our houses of worship and around our breakfast tables and use it to rock and roll America back on track. The key to ushering in this new great awakening is to be very, very loud.

The Alarming Truth About the U.K.’s Abortion Numbers

Last month, after a mysterious eighteen-month delay, the U.K. government finally published the 2023 abortion figures for…

When the Means Undermine the End

An introductory course in moral theology will include that the end does not justify the means. It’s…

Frequenting the Frontlines of Life

It was a brisk early morning when I set off from the John Jay Institute last Friday…