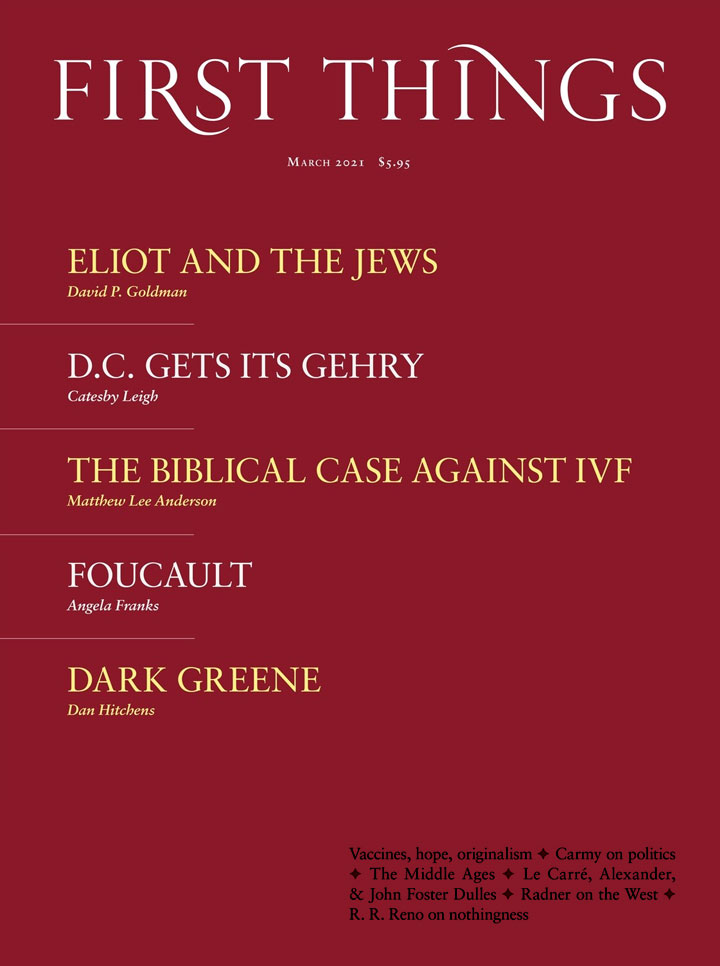

Russian Roulette:

The Life and Times of Graham Greene

by richard greene

little, brown, 591 pages, £25

Readers of Russian Roulette: The Life and Times of Graham Greene may finish the book with a sense of relief. That isn’t the fault of the biographer Richard Greene (no relation), who has done an impressive job of tying together the many strands of the novelist’s life. It’s just that Greene’s story is such a sad one. Sad in his personal life: Greene experienced estrangement from his wife, a string of doomed affairs, and an addiction to prostitutes. Sad politically: Greene clung to vague revolutionary hopes, befriending Fidel Castro and flattering Mikhail Gorbachev, without finding a cause he could really stand for. Sad religiously: Though his novels did so much to define modern Catholicism, Greene drifted into a kind of eccentric semi-Christian agnosticism. Sad in the most obvious sense of all: “It simply seems that I’m beastly & that’s that,” he wrote to his mistress Catherine Walston. “I love you dearly & I hate myself so much.”

At such moments, you sense that Richard Greene (henceforth R.G. to avoid confusion) would like to slap the novelist on the back and tell him to stop being so hard on himself. R.G. defends Greene from his critics—notably from “journalists looking for easy copy” who don’t realize that “the disasters, especially of his marriage and sexual life, are generally more pitiable than culpable.” Greene was, his biographer points out, a tormented man: He was diagnosed with manic depression and in middle age attempted suicide. Greene also claimed to have played Russian Roulette in his teens. R.G. casts doubt on the story, but not on Greene’s longing for danger. Greene wrote of Belize City, “Perhaps the charm comes from a sense of the temporary, of the precarious, of living on the edge of destruction.” That was the sort of place where Greene liked to spend his time.

He could be kind and generous—R.G. notes how freely he opened his wallet for hard-up acquaintances—but his dark side was never far away. Two testimonies not quoted in this biography: Greene’s friend Shirley Hazzard described his “playground will to hurt, humiliate, ridicule,” and Geoffrey Wheatcroft, who knew him late in life, observed: “He loved to tease and he loved practical jokes: both symptoms of unhappiness.” Some of Greene’s pranks—for instance, ringing up a retired solicitor called Graham Greene and pretending to be an irate member of the public (“Are you the man who writes these filthy novels?”)—smack of self-hatred more than playfulness.

Greene himself traced his troubles back to two schoolmates who bullied him. “What a lot began with Wheeler & Carter,” he confided to his mistress at the age of forty-six: “suspicion, mental pain, loneliness, this damned desire to be successful that comes from a sense of inferiority.” The other aspect of Greene’s unhappiness was his restlessness—what he called a “life-long war against boredom.” Wherever there was war or revolution, Greene would turn up in his short-sleeved white shirt. He worked for British intelligence in West Africa, witnessed the First Indochina War, the Mau Mau insurrection, and the bloody aftermath of the Six-Day War, argued with the Maoist Mayor of Chongqing about the treatment of dissidents, and was hysterically denounced by “Papa Doc” Duvalier’s Haitian regime. In Latin America, he became a kind of all-purpose mover and shaker: When the South African ambassador to El Salvador was kidnapped by guerrillas, Greene was the natural choice to negotiate for his release. In a letter to his mother, Greene summed up his life as “useless and sometimes miserable, but bizarre and on the whole not boring.”

Greene’s protagonists also struggle with boredom. “I went—for I had nothing better to do—to the Press Conference,” says a foreign correspondent. A man writes in a secret note to a woman, “I love you more than myself, more than my wife, more than God I think. . . . I want more than anything in the world to make you happy,” before pondering glumly on the “banality of the phrases.” Greene could be bored even by his most ingenious plots. Brighton Rock begins with a clever conceit: A man is on the run from homicidal gangsters—but his job is to be spotted as part of a newspaper competition. You settle in for the ride; and then, somewhere around the end of chapter two, Greene kills off the hero and switches his attention to the inner spiritual drama of a psychopathic Catholic mobster.

Greene knew how to craft a gripping thriller—this was the cocreator of The Third Man—or a sublimely funny comedy like Our Man in Havana. But he found himself pulled into writing dark religious fables instead. Catholicism was, apart from anything else, the ultimate backstop against boredom. You can get bored with crime, but not when the punishment could be eternal. A failing marriage can’t be merely tedious when the parties are bound together by an indissoluble vow unto death.

Greene became a Catholic at age twenty-one. He did so, in the first place, because he was trying to persuade the devoutly Catholic Vivien Dayrell-Browning to marry him. But Greene also came to admire the priest who instructed him: “I like him very much,” he wrote to Vivien. “I like his careful avoidance of the slightest emotion or sentiment in his instruction.” Greene found Catholicism impervious to sentimentality as well as resistant to boredom. He once speculated that God answers some prayers “as a kind of test of man’s sincerity and to see whether in fact the offer was one merely based on emotion.” It’s a revealing observation—not about God, but about Graham Greene. Sincerity, in Greeneland, is always a little suspicious, and needs to be tested: Is there anything to it apart from overwrought feeling? In the four major “Catholic novels”—somewhat successfully in Brighton Rock and The Heart of the Matter, very successfully in The Power and the Glory and The End of the Affair—Greene’s cynicism acts like acid, stripping away emotion until all that is left is the plain, supernatural reality. A priest may be a pathetic drunkard who has broken his vow of chastity—nevertheless, he remains a priest with the power to say Mass. A sexual relationship may be the most exhilarating, life-affirming experience—nevertheless, if one of the parties is married, it is simply adultery and has to be renounced. Receiving the Eucharist might seem a necessary social duty—yet to do so in a state of mortal sin is an indescribably grave offense.

In his review of The Heart of the Matter, Evelyn Waugh summed it up:

There are loyal Catholics here and in America who think it the function of the Catholic writer to produce only advertising brochures setting out in attractive terms the advantages of church membership. To them this profoundly reverent book will seem a scandal. For it not only portrays Catholics as unlikable human beings but shows them as tortured by their faith.

Another equally accurate response came from Pope Pius XII. After reading The End of the Affair, the Pontiff gravely remarked to an English bishop: “I think this man is in trouble. If he ever comes to you, you must help him.”

Greene certainly was in trouble, and though The End of the Affair is not simply autobiography, it portrays the anguish of Greene’s long relationship with Catherine Walston. It was Catherine who finally ended it, but not before the affair had wrecked Greene’s marriage. In a letter to his wife after she had discovered the infidelity, Greene explained that he “should always, & with anyone, have been a bad husband.” Adultery, he informed Vivien, was a “symptom” of his general “disease,” a disease that was regrettably necessary to his writing.

In general, R.G. tries not to dwell on Greene’s chaotic personal life, and mercifully he does not follow the example of a previous biographer who included, as an appendix, Greene’s list of his forty-seven favorite prostitutes. But the battle for supremacy between Catholicism and erotic love was perhaps the defining contest of Greene’s life. On a visit to Apulia, he was transfixed by a Mass said by the Franciscan Padre Pio. The friar, who would be canonized in 2002, invited Greene and Catherine to come and speak to him; Greene refused, saying that he feared meeting a saint might force him to change his life. (Presumably because he would have to give up Catherine.) For the rest of his life, Greene carried two pictures of Pio in his wallet. They were a link to the happy existence he might have had.

Any attempt to make sense of Greene’s Catholicism, especially in his latter decades, is likely to become a wild goose chase. He admired Pope Paul VI—a fan of Greene’s novels—but protested publicly against Humanae Vitae. Late in life, Greene criticized modernist theologians for denying the truth of the Crucifixion, before declaring in the next breath that if the Church said “the Trinity was no longer an article of faith, that would barely disturb my faith.” Sometimes he called himself a “Catholic atheist,” sometimes a “Catholic agnostic.” More than once, he described himself as a gnostic, which would explain a lot about his novels: the predominance of evil, the semi-disgusted fascination with bodily processes, the discomfort with marriage and family, the treatment of religious doctrine as a kind of secret knowledge, the idea—expressed in The Honorary Consul—that God has “a night-side as well as a day-side.”

Greene tried, throughout his life, to forge a kind of Catholic politics that was neither communist nor capitalist. He regularly criticized socialist revolutionaries and Soviet human rights abuses, while also warning against the cultural effects of globalization—“the gadget world of the States”—and delivering, in The Quiet American, a brilliant portrait of how idealistic Western intervention can end in mass bloodshed. But he was, in the end, too sentimental about communism. “If I had to choose between life in the Soviet Union and life in the United States of America, I would certainly choose the Soviet Union,” he claimed in 1967. Twenty years later, in a speech at the Kremlin, Greene enthused: “We are fighting—Roman Catholics are fighting—together with Communists, and working together with Communists. . . . There is no division in our thoughts.”

Greene was at his worst when he was most opinionated. Unfortunately, he became convinced in the 1950s that he ought to give his theological eccentricities free rein. “What fun is there in writing if one doesn’t go too far?” he wrote in a 1954 letter. “What makes me a ‘small’ writer is that I never do. There’s a damned cautiousness in what I write.” Yet Greene’s cautiousness, by preserving Catholic orthodoxy in his novels, had made possible the tension at the heart of them, between the ignominy of human existence and the awesome unchangeability of the Church. Stuck in a squalid jail, repulsed by his fellow prisoners, the priest in The Power and the Glory reflects:

It was for this world that Christ had died; the more evil you saw and heard about you, the greater glory lay around the death. It was too easy to die for what was good or beautiful, for home or children or a civilization—it needed a God to die for the half-hearted and the corrupt.

Not many twentieth-century writers managed to make Christian doctrine seem urgently contemporary, a living, active thing in the age of world war, postcolonialism, and mass media. Greene is in that small club. He explored the limits as well as the ultimate mysteriousness of God’s mercy in a way that was both startling and immediately recognizable as true. When The End of the Affair came out, Greene’s friend Fr. Gervase Mathew wrote to congratulate him: “You said so much that I have seen so often in life but never before in print.”

Dan Hitchens writes from London.

The Testament of Ann Lee Shakes with Conviction

The Shaker name looms large in America’s material history. The Metropolitan Museum of Art hosts an entire…

What Virgil Teaches America (ft. Spencer Klavan)

In this episode, Spencer A. Klavan joins R. R. Reno on The Editor’s Desk to talk about…

“Wuthering Heights” Is for the TikTok Generation

Director Emerald Fennell knows how to tap into a zeitgeist. Her 2020 film Promising Young Woman captured…