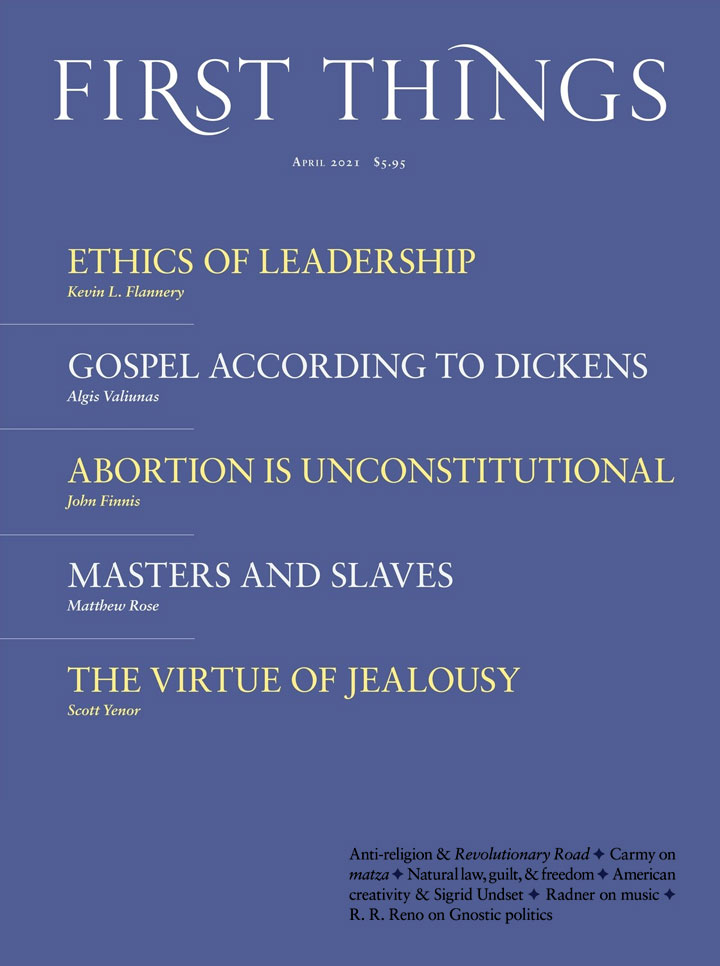

In the popular understanding of Christmas, Charles Dickens’s 1843 novella looms large. A Christmas Carol seems to represent not only Christmassy warmth, fellowship, and cheer, but the very essence of Christian practice. At the end, Ebenezer Scrooge, the old skinflint, is redeemed by an act of charity. It would be too much to say that Scrooge’s embrace of Tiny Tim has replaced the Christ child at the sacred and heroic center of the season, but the Dickensian vision of charity as open-handedness to the poor has acquired the status of gospel truth.

One need not read Dickens’s tale to absorb the message. With some frequency, a new film version of the story will appear, reacquainting us with the Gospel According to Dickens. Bill Murray and Mr. Magoo have incarnated Scrooge on screen, contributing a very modern hilarity to Dickens’s original, which is uncharacteristically short on belly laughs. A 2017 movie about the writing of A Christmas Carol enshrines Dickens as The Man Who Invented Christmas.

Dickens exerts such power because he recognized that Christmas cheer must come to terms with a cruel world. Scrooge is moved toward conversion of heart by the Ghost of Christmas Present—a “jolly Giant, glorious to see,” who comes amid a heap of delicious foods, which Dickens catalogues with Rabelaisian gusto. But Christmas Present conceals under his voluminous robes two cadaverous children:

They were a boy and a girl. Yellow, meagre, ragged, scowling, wolfish; but prostrate, too, in their humility. Where graceful youth should have filled their features out, and touched them with its freshest tints, a stale and shrivelled hand, like that of age, had pinched, and twisted them, and pulled them into shreds.

These children, Ignorance and Want, are the terrible offspring of the Gospel of Mammonism, the term used by Dickens’s friend Thomas Carlyle to describe the “laws-of-war, named ‘fair competition’ and so forth.” Only thorough schooling in the misery of others—provided one is not reduced thereby to misery as well—earns the joy our hearts truly deserve. Compassion must precede magnanimity. The Christmas spirit requires a preparation of the heart, feeling what the wretched feel, then doing what one can to relieve their agony. Tiny Tim does not die, and his benefactor Scrooge is reborn, irradiated with goodness and happiness.

Countless readers, including great artists, have loved and revered Dickens. He met with commercial success and was a celebrity in his lifetime. Those devoted to his novels relish his comic creatures, his advocacy for the downtrodden, his love of middle-class peacefulness, tidiness, prudence, and comfort, his resolute insistence that goodness will overcome evil, and his belief in an invisible order that is the source of ultimate solace and meaning. He was as Christian as Christmas itself—but perhaps that means he was less Christian than he ought to have been. It is only too easy to regard Dickens as a true believer in kindness and generosity, which is to say, in humanism at its finest.

That, at any rate, is the general assessment of scholarship today. The professors who write about Dickens pass over scenes such as the heavenly host of children who visit the sick Jenny Wren in Our Mutual Friend and the ministrations of “angel hands” that grace Little Nell’s deathbed in The Old Curiosity Shop. (The latter prompted Oscar Wilde’s immortal bon mot: “One must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing.”)

Humphrey House founded modern academic Dickens studies with The Dickens World (1941). He cannot contain his contempt for Dickensian death scenes. As Jo, the young crossing-sweeper in Bleak House, expires, he is prompted to repeat with his last breaths the opening words of the Lord’s Prayer, which he is evidently hearing for the first time. House is livid at Dickens’s “failure to assimilate and dignify the fact of suffering and waste. . . . Apart from the use of religious terms, it is the pleasurable self-indulgence of these scenes that is so distasteful and, incidentally, so unchristian.”

House is mistaken. The scene evokes an authentic emotional force that is achieved without strain. What the critic really finds so objectionable is Dickens’s conviction that the child’s suffering and death cannot be countenanced as “waste.” Dickens confessed that his fictional creatures were sometimes more real to him than the flesh-and-blood people he knew, and he wept when writing some of his most sorrowful pages. It is apparent in this passage that Jo’s creator believes the boy’s soul is actually returning to the Father. The prospect of joy in eternal life outweighs the evils of this world.

Dickens was not Panglossian, however. He expressed scorn for the society that insults and injures the weak and vulnerable. In Bleak House (and elsewhere), the reader feels the heat of his anger that Jo’s extinction is of no consequence to the prosperous people who live at a comfortable remove from poverty and squalor: “Dead, your Majesty. Dead, my lords and gentlemen. Dead, Right Reverends and Wrong Reverends of every order. Dead, men and women, born with Heavenly compassion in your hearts. And dying thus around us every day.” Dickens comprehends the temporal and eternal significance of Jo’s dying; he rages against injustice and trusts in redemption. Only someone who comprehends them both can do justice to the life and death of mortal men.

Leo Tolstoy recognized the theological character of Dickens’s genius. In a 1904 letter to the Englishman James Ley, who had asked his opinion of Dickens, he wrote (in English): “I think that Charles Dickens is the greatest novel writer of the 19th century, and that his works, impressed with the true Christian spirit, have done and will continue to do a great deal of good to mankind.” This assessment came late in Tolstoy’s life, when he was spiritually militant. He had denounced his own greatest novels as trifling entertainments for the idle, defied the state-sanctioned Orthodox Church, and constructed his own personal version of Christianity, in which the Sermon on the Mount and the novels of Dickens assumed commanding significance. But there is an important difference between Tolstoy and Dickens. The Russian novelist worshiped the God of the Poor, who in his eyes were the only souls worthy of heaven. Dickens believed that God looks kindly on the poor, but in his literary imagination the divine also accords favor to those with sufficient talent and energy to rise to a higher station in this life, as he had done himself.

This valorization of worldly achievement is Dickens’s concession to the Gospel of Mammonism. In Past and Present, Carlyle pinpoints the fear that drives “the modern English soul” to relentless work: “The terror of ‘Not succeeding;’ of not making money, fame, or some other figure in the world—chiefly of not making money! Is not that a somewhat singular Hell?” In his own life, no amount of adulation and wealth would ever be enough for Dickens. He died of a stroke at fifty-eight, completely spent by the merciless monthly deadlines for the serial publication of his novels, the editing of a magazine for which he wrote a substantial part of the copy, and the barnstorming public readings of his favorite works, which propelled him all over England and America. Thus, though Tolstoy understands Dickens better than the professoriate does, and though in his praise we observe one surpassing genius extolling another as his superior, he may not in fact be the most reliable judge of Dickens’s particular greatness, or the most perceptive observer of Dickens’s demoniacal ambition.

Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay “Phases of Fiction” homes in on the characters in Dickens’s novels. Their vivid portrayal, which borders on caricature, opens to the reader the half-hidden abundance of human life, which we often lack the mettle to encounter in actual fact:

The character-making power is so prodigious, indeed, that it has little need to make use of observation, and a great part of the delight of Dickens lies in the sense we have of wantoning with human beings twice or ten times their natural size or smallness who retain only enough human likeness to make us refer their feelings very broadly, not to our own, but to those of odd figures seen casually through the half-opened doors of public houses, lounging on quays, slinking mysteriously down little alleys which lie about Holborn and the Law Courts.

The world of Dickens is his exclusive preserve, an alternative to the reality we inhabit. It operates according to rules of its own; but that fictive world arouses the reader’s imagination, providing tantalizing glimpses of everyday lives we rarely allow ourselves to see. As Woolf observes, “We enter at once into the spirit of exaggeration.”

Abram Tertz was the pseudonym of Andrei Sinyavsky, a Soviet political prisoner at forced labor from 1966–1971. He put his confinement to use in A Voice from the Chorus, a gathering of reflections originally written as prison letters to his wife. His understanding of Dickens combines Woolf’s appreciation of comic brio with Tolstoy’s praise of spiritual grandeur: “Two writers, [E. T. A.] Hoffmann and Dickens, have shown to us that humor is love. They have revealed to us that God takes a humorous view of mankind. In humor there is both tolerance and encouragement. ‘Bravo!’”

There aren’t many laughs in the Bible or the Summa Theologica. The ridiculous, the preposterous, the uproarious: We are tempted to regard these parts of the human condition as far removed from the official Godhead. But this sentiment suggests self-protection, not sound theology. Man plans, God laughs; it is often rather a disagreeable arrangement, from our point of view. So we are accustomed to regarding him with ceremonious solemnity, always on our best behavior when we approach. Dickens breaks with decorum and thereby proclaims a new dispensation. He establishes laughter as an essential duty for the pious.

And Dickens is ever devoutly observant. The comic genius no doubt feels God’s pleasure when he creates the tubby little gent with a warrior’s spiritedness, Mr. Pickwick, or the tippling gabby midwife with her own system of English pronunciation, Mrs. Gamp; the perennially bankrupt but endlessly charming sponger, Mr. Micawber, or the addled philanthropist hell-bent on civilizing Borrioboola-Gha, Mrs. Jellyby; the gay dog with a bounder’s eye for the main chance, Major Bagstock, or the intrepid one-armed mariner with a deathly fear of his landlady, Captain Cuttle. Every human oddity Dickens creates should be seen as an offering of thanks to the God who created him. Humor is Dickens’s most formidable weapon against the world’s evil, putting the unbearable to rout under a hail of laughter. In the face of heartless life and hard death there exists in Dickens’s soul an inexhaustible store of amusement, as comforting as prayer.

Hilarity came to Dickens as naturally as breathing. But when seriousness was called for, he was a sober Victorian patriarch, with all the honorable gravity and profound sense of responsibility that noble position demanded and enjoyed. He was close friends with Angela Burdett Coutts, one of the wealthiest heiresses in England. They joined forces to found Urania Cottage in West London, a home for the rehabilitation of “fallen women,” some dozen at a time, most of them prostitutes who had served prison sentences, but some merely young unfortunates who had violated the severe public code of sexual probity. Miss Coutts poured her wealth into the project, while Dickens poured his colossal energy into it, seeing to the procurement of furniture, books, carpets, and new clothes for the inmates. He also wrote a letter, as he alone could write, which was distributed by prison wardens to women who seemed remorseful and eager to reform. The letter offered, with a tender word here and a stern one there, the chance to be “reclaimed.” Dickens was not a celebrity with a short attention span. He remained a tireless stalwart of Urania Cottage, which in his era was recognized as a triumph of philanthropy. There was scarcely a worthy cause to which he did not lend a helping hand.

No one better understood the connection in Dickens’s soul between his comic effervescence and his earnest, active solicitude than William Makepeace Thackeray, the novelist who was Dickens’s rival and friend. “Humour!” Thackeray exclaimed.

If tears are the alms of gentle spirits, and may be counted, as sure they may, among the sweetest of life’s charities,—of that kindly sensibility, and sweet sudden emotion, which exhibits itself at the eyes, I know no such provocative as humour. It is an irresistible sympathiser; it surprises you into compassion: you are laughing and disarmed, and suddenly forced into tears.

This passage is an encomium to Dickens’s literary and charitable accomplishments. More than any other person, Dickens has changed England decidedly for the better:

There are creations of Mr. Dickens’s which seem to me to rank as personal benefits; figures so delightful, that one feels happier and better for knowing them, as one does for being brought into the society of very good men and women. . . . Was there ever a better charity sermon preached in the world than Dickens’s “Christmas Carol”? I believe it occasioned immense hospitality throughout England; was the means of lighting up hundreds of kind fires at Christmas-time; caused a wonderful outpouring of Christmas good feeling; of Christmas punch-brewing; an awful slaughter of Christmas turkeys, and roasting and basting of Christmas beef.

Dickens’s teeming comic imagination does God’s work here on earth:

I may quarrel with Mr. Dickens’s art a thousand and a thousand times, I delight and wonder at his genius; I recognise in it—I speak with awe and reverence—a commission from that Divine Beneficence, whose blessed task we know it will one day be to wipe every tear from every eye.

Sometimes the sheer delight of creation so overwhelms Dickens that he has a hard time reining in his high spirits. Writing in 1846 to John Forster, his friend and first biographer, he tells of a wild rush of exuberance as he works on Dombey and Son: “Invention, thank God, seems the easiest thing in the world; and I seem to have such a preposterous sense of the ridiculous, after this long rest, as to be constantly requiring to restrain myself from launching into extravagances in the height of my enjoyment.” As he reports six weeks later, the enjoyment is catching: “The Dombey success is BRILLIANT! . . . I read the second number here last night to the most prodigious and uproarious delight of the circle. I never saw or heard people laugh so.” The Dickensian categorical imperative: Laugh until you’re breathless and your sides ache and everyone else in the room laughs with you. The laughing heart is the surest human connection to a loving Divinity. It fortifies souls inclined to despondency or despair with a saving courage; a grace is available to all those willing to choose levity over misery.

Sometimes Dickens inserts a note of levity even into the rawest tragedy. In Dombey and Son, the sweet innocent numbskull Mr. Toots pays a visit to Captain Cuttle, bearing bad news: The newspaper reports the sinking of a ship bound for the West Indies, with the apparent loss of everyone aboard. One of the passengers was Captain Cuttle’s friend Walter Gay, whom he loved like a son. Mr. Toots, unaware what Walter meant to the Captain, is surprised by the vehemence of the old salt’s sorrow. He offers bumbling consolation: “Somebody’s always dying, or going and doing something uncomfortable in it. I’m sure I never should have looked forward so much, to coming into my property, if I had known this. I never saw such a world. It’s a great deal worse than Blimber’s [boarding school].” Happily, it comes to light eventually that Walter has been saved, and he marries the marvelous Florence Dombey, whom Mr. Toots had long yearned for in his ridiculous, yet noble way. Dickens loves his poor boobies, but that does not mean they get the girl. The heroine is reserved for the hero, but Mr. Toots finds a more suitable mate in Susan Nipper, Florence’s loyal servant and friend. In Dickens’s moral universe, there is enough happiness to go around.

Evil gets its due in Dickens. Oliver Twist boasts perhaps the most memorable assortment of evildoers, from the swollen, venal, beadle Mr. Bumble and the workhouse overseers who make Oliver’s childhood an unrelenting ordeal, to the crew of thieves and murderers run by Fagin and Bill Sikes into whose hands the innocent falls. There is Oliver’s long-lost brother, Monks, who tries his damnedest to kill the sibling he hates and secure an inheritance for himself. These characters emerge from a miasma of social corruption. Well-heeled but unfeeling men permit the unspeakable to flourish. The resulting foulness of the poorest districts of London spawns ruffians like Sikes:

Rooms so small, so filthy, so confined, that the air would seem too tainted even for the dirt and squalor which they shelter; wooden chambers thrusting themselves out above the mud and threatening to fall into it—as some have done; dirt-besmeared walls and decaying foundations, every repulsive lineament of poverty, every loathsome indication of filth, rot, and garbage;—all these ornament the banks of Folly Ditch.

Those born and bred amid such pestilence are cut out for a very hard time. Nonetheless, Dickens never lets the reader forget that a man like Sikes gets exactly what he deserves. Maybe Dickens’s God—or is it only Thackeray’s?—will one day wipe every tear from every eye, but in this earthly life the criminal must pay the full price for his wrongdoing.

Other evildoers may be more appalling or ferocious, but none is so disgusting as Uriah Heep in David Copperfield. His “’umbleness,” the unctuous pretense of humility, cannot conceal his itch for revenge and domination. He hates his lowly station, resents his social superiors, and schemes to gain the whip hand over his employer, the virtuous but doddering Mr. Wickfield, whose daughter, Agnes, Heep aims to marry. His plot is foiled, and he ends up in prison for fraud.

Copperfield visits the prison warden, a former schoolmaster of his, and encounters his old nemesis, who pronounces himself so thoroughly chastened that he wishes David and the Wickfields could experience the moral benefits of such confinement. Heep is repulsive, but David is touched as the wretch reveals that his ’umble parents had brought him up to cower and fawn—the only way the likes of him could rise in the world. The social arrangements that deform souls like Heep’s have a lot to answer for in Dickens’s world. But simple justice must be served, and prison is the place for him. Dickens has the imagination of a reformer, not a revolutionary.

The evil madness of crowds is a theme of A Tale of Two Cities, whose action takes place during the French Revolution. Revolutionary justice knows only the law of vengeance, which is unreasoning, peremptory, and carried out at the insistence of the canaille: “The lowest, cruelest, and worst populace of a city, never without its quantity of low, cruel, and bad, were the directing spirits of the scene: noisily commenting, applauding, disapproving, anticipating, and precipitating the result, without a check.” The mob gathers at an immense grindstone to sharpen the weapons they are using to slaughter their prisoners, who are condemned by acclamation. Dickens paints the gory scene: “What with dropping blood, and what with dropping wine, and what with the stream of sparks struck out of the stone, all their wicked atmosphere seemed gore and fire. The eye could not detect one creature in the group free from the smear of blood.” The Old Regime aristocrats were criminally indifferent toward the poor, and their barbarities are savagely punished. And yet nothing is made good thereby. It is not any sense of right but rather the savagery of the wrong that Dickens sears into the reader’s mind.

In the miasma of historic wrong and bloody vengeance, the valor and goodness of Sydney Carton, who sacrifices himself to save the husband of the woman he loves, shine like a guiding star. As Carton ascends the steps to the guillotine, Dickens intimates that his sacrifice has an eternal reward: “I am the resurrection and the life, saith the Lord.” This is likely one of those passages that the author wept over as he was writing. No honest reader can deny that Dickens believes in his hero’s eternal salvation.

There will always be scoffers who assert that reading Dickens is a childish pastime and claim that the only worthy Victorian novelist is George Eliot. Ignore their carping. Better yet, dismiss them with a robust Dickensian laugh. That laugh may have a touch of the sardonic. There was a darkness in him. Dickens carried with him all his life the indignity and terror of having been put to menial labor in a shoe polish factory when he was twelve, and he was a cad to his wife after he fell in love with a much younger actress. But Dickens loved being alive, knew his life was a divine gift, and propagated that love and that knowledge wherever he went. It was this love that allowed him to construct the most extraordinary fictional world since Shakespeare’s: a world uniquely his yet unmistakably our own, poised precariously between good and evil, but tilting in the end toward the eternal victory of faith, charity, compassion, and delight. The canon is forever enriched by the Gospel According to Dickens. He penned a modern quasi-mythic trove of Christian wisdom and, above all, joy.

Bladee’s Redemptive Rap

Georg Friedrich Philipp von Hardenberg, better known by his pen name Novalis, died at the age of…

Postliberalism and Theology

After my musings about postliberalism went to the press last month (“What Does “Postliberalism” Mean?”, January 2026),…

Nuns Don’t Want to Be Priests

Sixty-four percent of American Catholics say the Church should allow women to be ordained as priests, according…