R. R. Reno

Editor

nIn the final days of July I finished Christopher Beha’s latest novel, The Index of Self-Destructive Acts. It’s the story of a data geek’s command of statistics in a tug-of-war with the poetic genius of a famous but over-the-hill newspaper columnist. But it’s much more than that. Beha brings his readers to see the lure of greatness and taste the sweet savor of forgiveness. His characters get lost in the thick fog of self-knowledge, and they experience the anguish of loss. It’s a wonderful, enrapturing novel of people, not ideas—though of course people have ideas, to which they are often self-destructively loyal.n

nMark Bauerlein

Contributing Editor

n

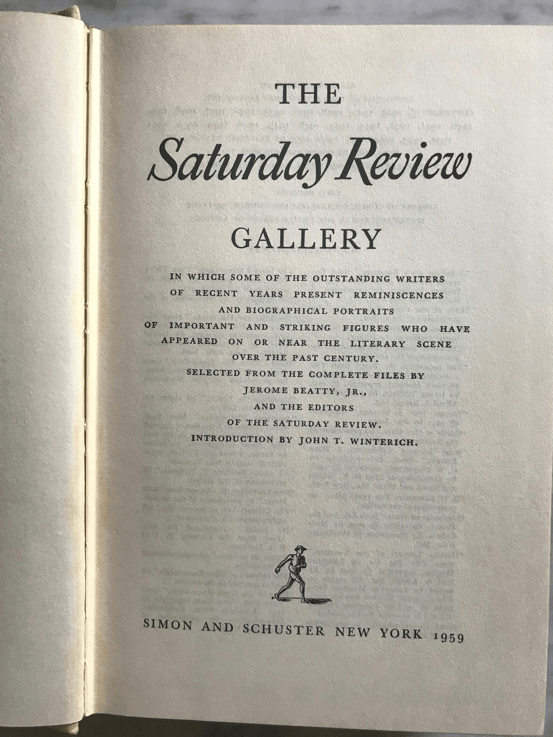

Pictured above is a collection from the mid-twentieth century (the Golden Age of literary culture in the United States). It’s a book of biographical and autobiographical profiles pulled from a few decades of The Saturday Review. We have:n

n

- Ford Madox Ford on Oscar Wilde: “Mr. Wilde was a quiet individual who came every Saturday, for years, to tea with the writer’s grandfather—Ford Madox Brown.”n

- Historian Frederick Lewis Allen, who wrote popular chronicles of the 1920s and ’30s on Horatio Alger: “He wrote about success, pluck and luck, but he personally didn’t have much of them.”n

- G. K. Chesterton on Thomas Hardy, Yeats, and others: “For this was the rather tremendous truth about Hardy: that he had humility.”n

- Hilaire Belloc on Chesterton: “I was not when I first met him as alive to the strength of that word Catholic as I am today.”n

- Langston Hughes on “Harlem literati”: “Strange thing about the Negro Renaissance that boomed and bloomed in Harlem. Practically none of the Negroes taking part in it were Harlemites.”n

- Richard Aldington on Ezra Pound: “Unfortunately, Ezra had read Whistler’s Gentle Art of Making Enemies, which he practiced without the ‘gentle.’”n

- Max Eastman on John Dewey: “The man who saved our children from dying of boredom in school.”n

- Edith Hamilton on William Faulkner: “Mr. Faulkner’s novels are about ugly people in an ugly land.”n

The whole thing is a testimony to the literary scene when that scene was understood as central to the condition of American society.n n

Veronica Clarke

Assistant Editor

n“It’s May and I’ve just awakened from a nap, curled against sagebrush the way my dog taught me to sleep. . . . A front is pulling the huge sky over me, and from the dark a hailstone has hit me on the head.” n n

In 1976, Gretel Ehrlich went to Wyoming to film sheepherders in the Bighorn Mountains for PBS. After losing a loved one—a self-shattering experience that left her “waking up not knowing where I was, whether I was a man or a woman, or which toothbrush was mine”—she stayed to become a sheepherder herself. “I wasn’t losing my grip,” she insists. Her friends think she is “hiding out.” But Ehrlich’s The Solace of Open Spaces, a collection of “raw journal entries” written to a friend in Hawaii over the course of five years, proves that when it comes to the harsh, indifferent landscape of Wyoming, there is no hiding. n n

Wyoming, as the book’s opening lines suggest, has a way of hitting you over the head and waking you up. Having lost her appetite for “city surroundings, old friends, familiar comforts,” Ehrlich immerses herself in the stark, lunar planes of the least populated state in the United States—a place where “men become hermits,” “women go mad,” and where winter lasts half the year: “Wyoming seems to be the doing of a mad architect—tumbled and twisted, ribboned and faded, deathbed colors, thrust up and pulled down as if the place had been startled out of a deep sleep and thrown into a pure light.” The “open spaces” can make you feel like you’re surrounded by spectators—the rocks, the wind, the sun—a bodily awareness akin to the feeling of being watched, of being “thrown into a pure light.” n n

Ehrlich, of course, does sometimes encounter actual people. The men and women she meets and befriends—sheepherders and cowboys, old alcoholics and feuding sisters—possess, like the landscape, both gentleness and severity. They are independent and isolationist, open and compassionate, quirky and polite: “In all this open space, values crystalize quickly.”n n

A desolate landscape though it may be, Wyoming is (to borrow Seamus Heaney’s observation about landscapes in general) a sacramental space, one through which Ehrlich ultimately comes to recognize that “loss constitutes an odd kind of fullness,” and “despair empties out into an unquenchable appetite for life.”

First Things depends on its subscribers and supporters. Join the conversation and make a contribution today.

Click here to make a donation.

Click here to subscribe to First Things.

Bladee’s Redemptive Rap

Georg Friedrich Philipp von Hardenberg, better known by his pen name Novalis, died at the age of…

Postliberalism and Theology

After my musings about postliberalism went to the press last month (“What Does “Postliberalism” Mean?”, January 2026),…

Nuns Don’t Want to Be Priests

Sixty-four percent of American Catholics say the Church should allow women to be ordained as priests, according…